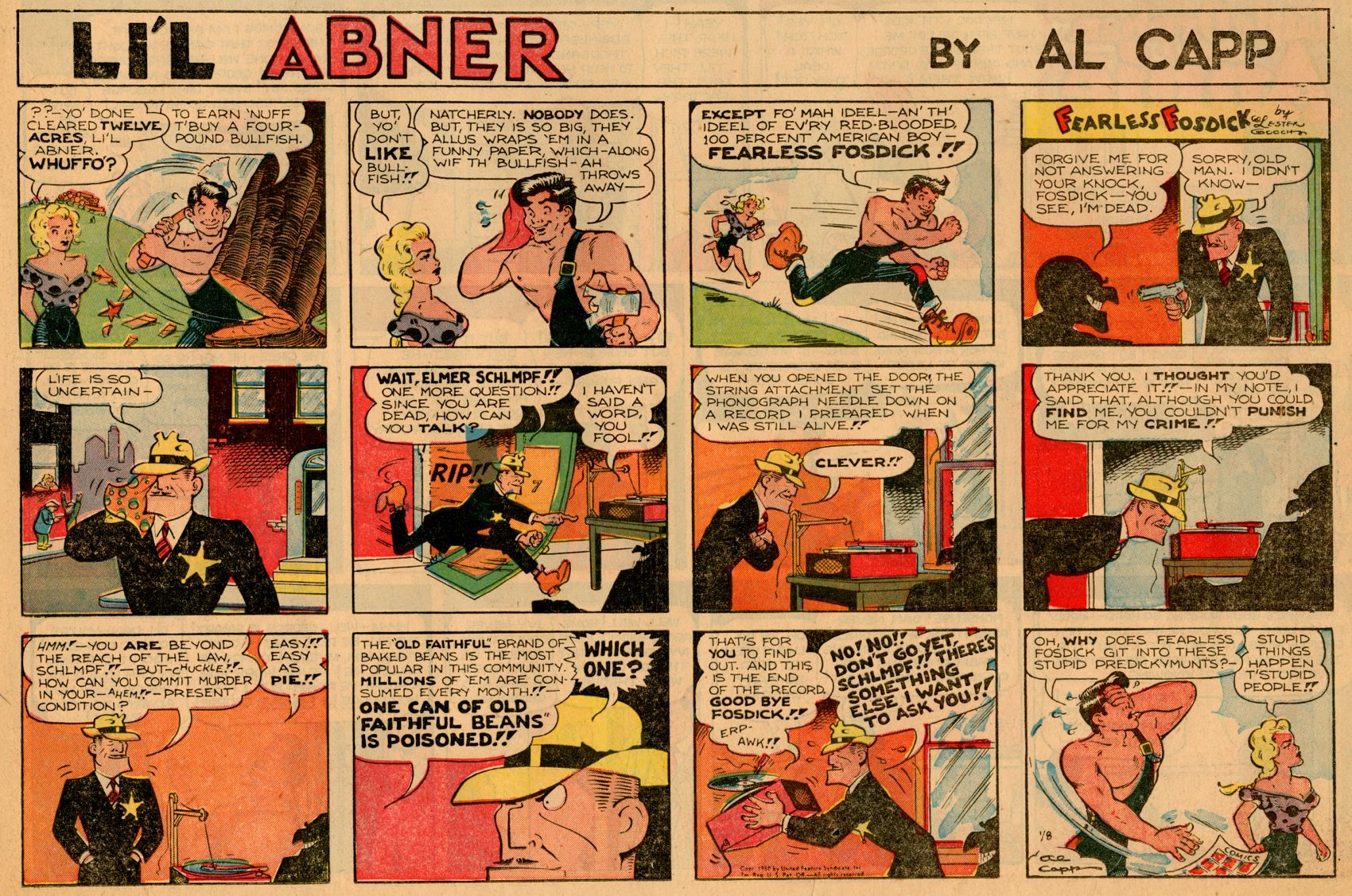

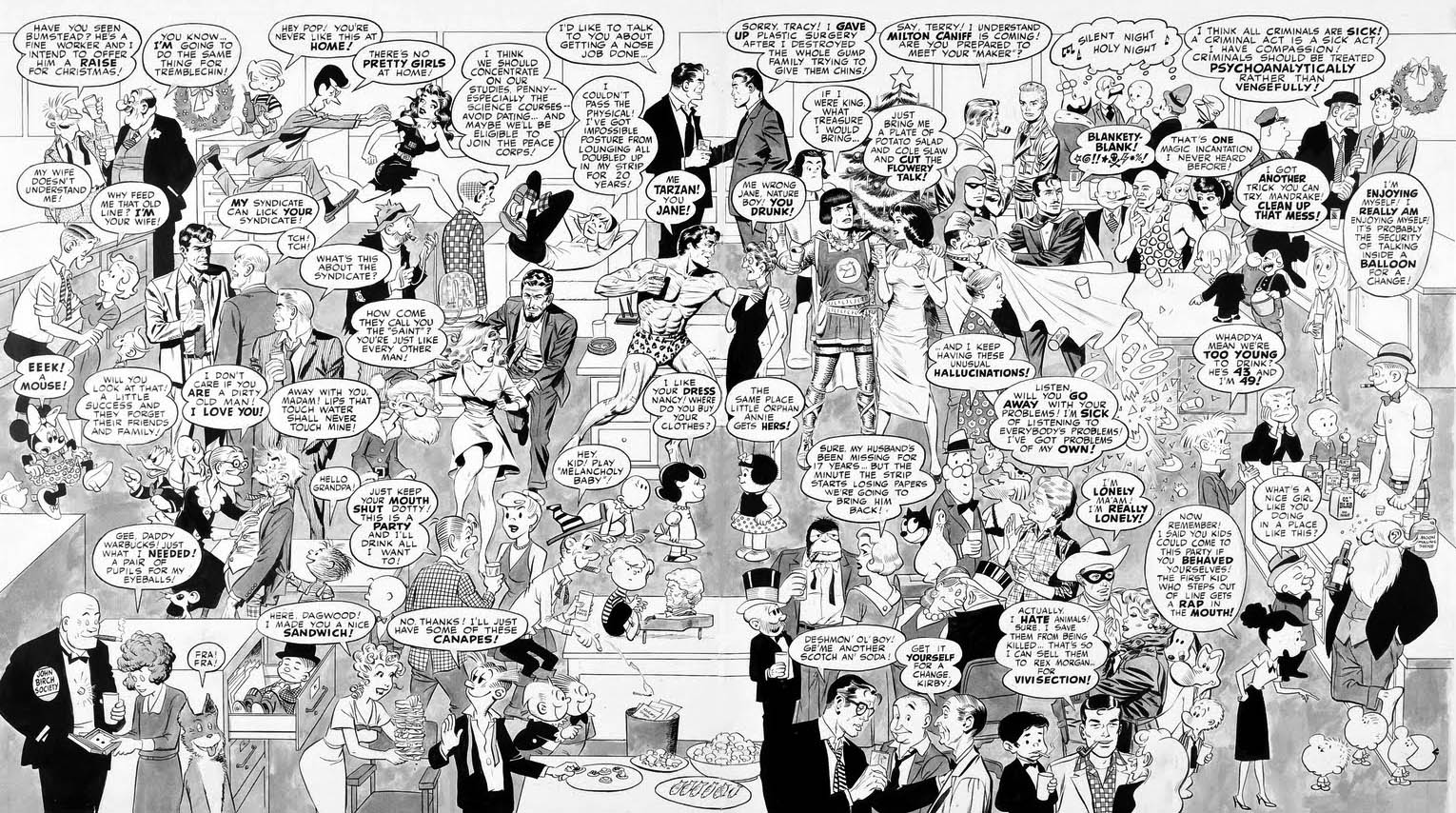

For my money, Li’l Abner is the funniest of all the classic American comic strips. (A couple of the episodes featuring Fearless Fosdick, a merciless parody of Dick Tracy, are the only comic strips this side of Mad Magazine that have ever made me laugh out loud.)

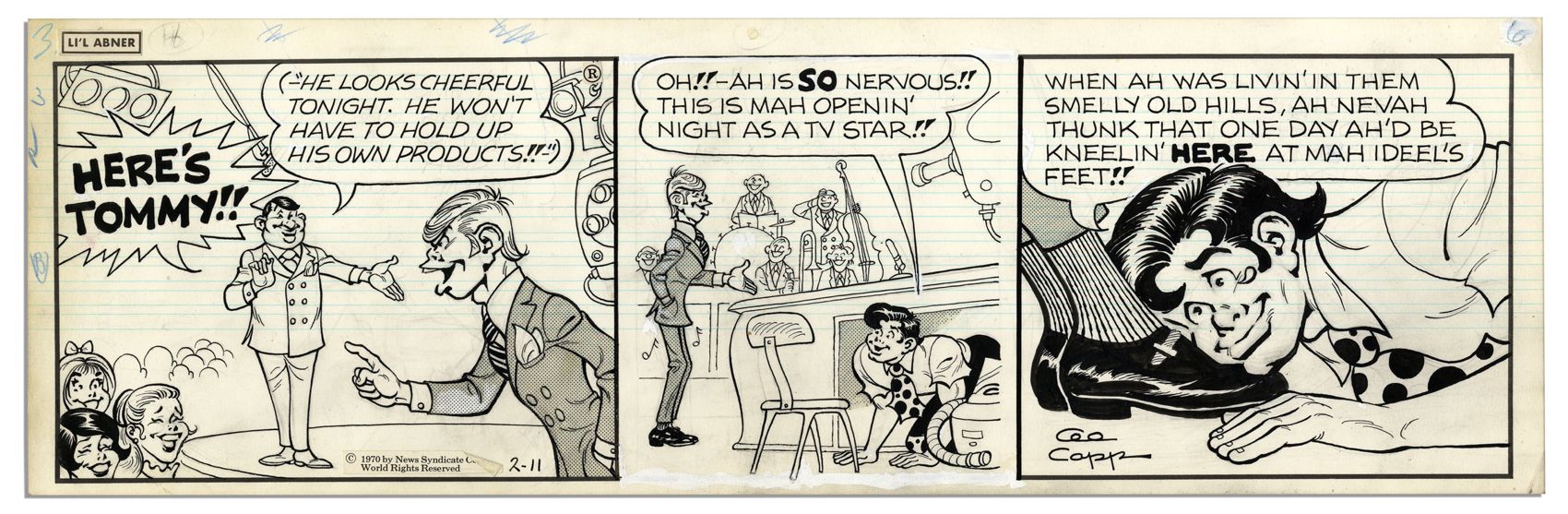

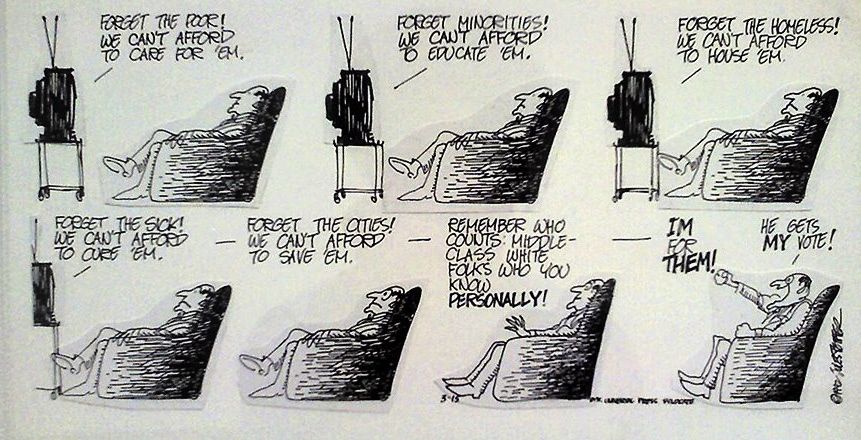

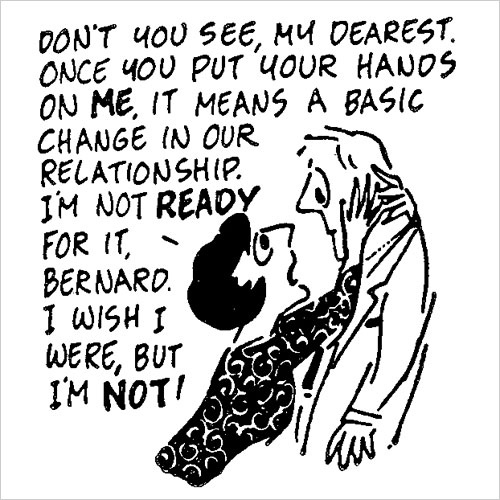

Al Capp, Abner’s creator, had a lively sense of the absurd, which he combined with a relentless cynicism to fashion a comic tone all his own, somewhere between slapstick farce and satire. The hillbilly inhabitants of Dogpatch, Abner’s home town, are both wise in their ways and idiotic — Capp ridicules them even as he uses them to ridicule the more sophisticated characters they meet.

Nothing is sacred in Capp’s view of things, everyone is preposterous. It’s an attitude that keeps the reader off balance, ready to be elbowed unexpectedly in the ribs by some outrageous gag or other. Comedy and sentiment rarely mix well — Capp’s total avoidance of sentiment frees him up for creating laughs at will.

There are echoes in this approach of the tone of E. C. Segar’s Popeye strips, with their manic knockabout gags and omnidirectional violence, but Popeye always remains heroic in his bullheaded way. Abner is always a boob, even when he’s doing the right thing, usually by mistake.

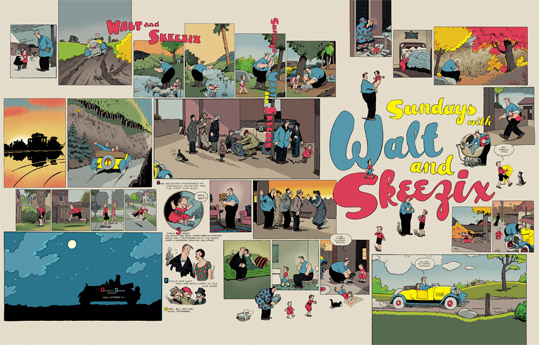

Capp’s strip is one of the few great ones that hit the ground running. Abner, Daisy Mae, Mammy and Pappy Yokum appear fully fledged from the start, ready to carry the strip onwards for decades.

Click on the images to enlarge.