Part two of Paul Zahl's essay on the novel By Love Possessed and its screen adaptation:

A NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET (Part Two)

Arthur Winner's “nightmare on Elm Street” begins when a Roman Catholic

lady friend of Marjorie Penrose attempts to convert him to the true

church in the setting of a rose garden that bears remorseful memories of his

affair with Marjorie, the wife of his law partner. This Mrs. Pratt

corners Arthur Winner and very skillfully, and craftily, turns the

conversation in the direction of his past sins, which Marjorie has

apparently confessed to her. Just when the Man of Reason thinks he is,

as usual, in quiet control of things, Mrs. Pratt harpoons him. She spears him straight to the heart: “Thou art the man”. Arthur

Winner is only saved from complete humiliation by the appearance, in

the underbrush, of a snake!

From this point on, the humbled hero of By Love Possessed is so fully

de-constructed that he has no choice but to take his famous literary

walk from the steps of Christ Church (Episcopal), where he has been

ushering at the Sunday morning service and where he is to become the

next Senior Warden, over to the crucial Detweiler House, then past the

Courthouse and the Christ Church again, past his law office, past

the Union League Club (moribund and soon to close), past the

storefronts of Main Street and beyond, up the street where the old

families of Brocton used to live, right up to the entrance of the house

in which he was born and where his mother still lives, to make his

great and ever remembered (for those who read the book) entrance,

calling upstairs to his aunt, his mother, and his wife.

This is Arthur's nightmare, a universal dereliction of disillusionment,

by which he must catch at hope in a new way. I, for one, find the last

five pages of By Love Possessed satisfying, real, and ennobling. They

took me by surprise. I think about them every day.

How does the movie version envisage the emotionally overwhelming finish

of the book? The answer is, not very well. As Cozzens himself

remarked, in his journal entry describing his second viewing of the

movie in Williamstown, the script writer had collapsed some characters,

and had to diminish the inwardness of the book. So much of this novel

is inner dialogue, inner qualifyings, inner voices of contradiction,

and association; inner asides, both cruel and kind. Thus the

cascading, baroque language of the book is lost in the movie. Of

course it is lost. The visual image is not the same as the written

word.

In its ambitious attempt to put this complicated story in a narrative

without flashback, into a linear tale which takes you somewhere, the

movie fails. I don't see how anyone would really dissent from that

judgment. By Love Possessed The Movie flattens everything out. It

has only its story to tell, brick by brick, or step by step. No one

has gotten inside the story and then developed it cinematically, either

through the composition or the editing. The building and billowing

mood of the book, and also the philosophy of resignation that the book

embodies: they're not on film.

Only in two sections, so far as I can see, do the director and crew get

under the story, to what it is really about — which is the shipwreck

of love that attempts to possess, the forms of love that try to possess

the loved object. Loving that possesses the lover, and thus is about

the lover rather than the beloved — whether it be the love of a parent

for a child, of a husband for a wife, of a high-school girlfriend for

her selfish boyfriend, of an old patrician man for his reputation in

the town, or, in a case so important to this novel, of a “responsible”

older sister for her feckless younger brother — possessive love makes

catastrophes of human relationships. The book is about the victory, in

utter failure, of a man who overcomes the possessiveness of love in

order to, well, live, and then, counter-intuitively, love. That man is

Arthur Winner. What Arthur Winner stumbles on, you might say, is the

victory of resignation, the acquiescence of defeat which results in a

simple solution of simply taking the next step in good faith.

Only in two sections of By Love Possessed The Movie is the deeper

interest of this material expressed visually. There's a lot more

footage outside of these two sections, but it has an almost indifferent

quality of detachment (the wrong kind), which is not philosophical

detachment but rather, “I think we'd better film this thing as quickly

as possible, grin and bear it, and get our product into theaters while

people can still remember reading the book a couple years ago.”

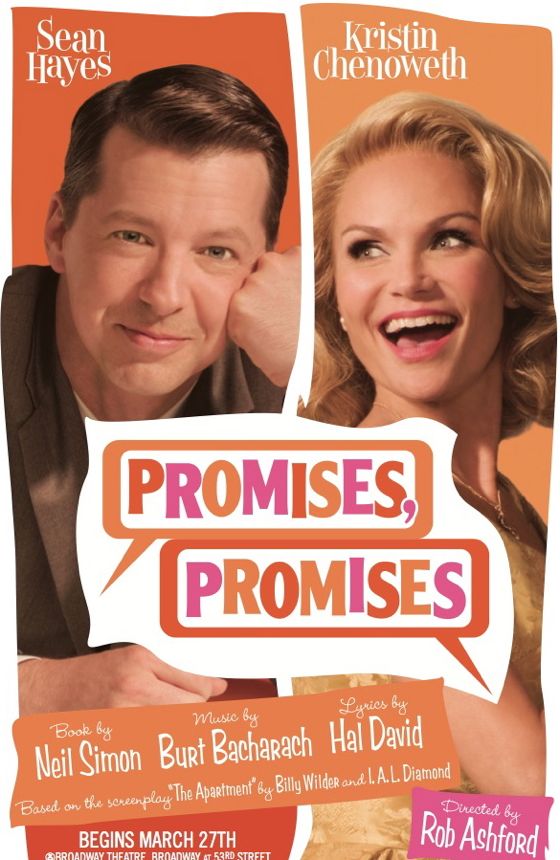

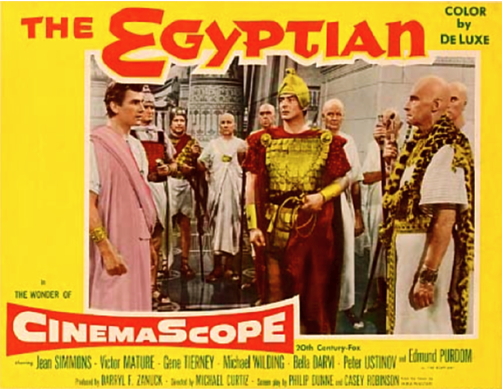

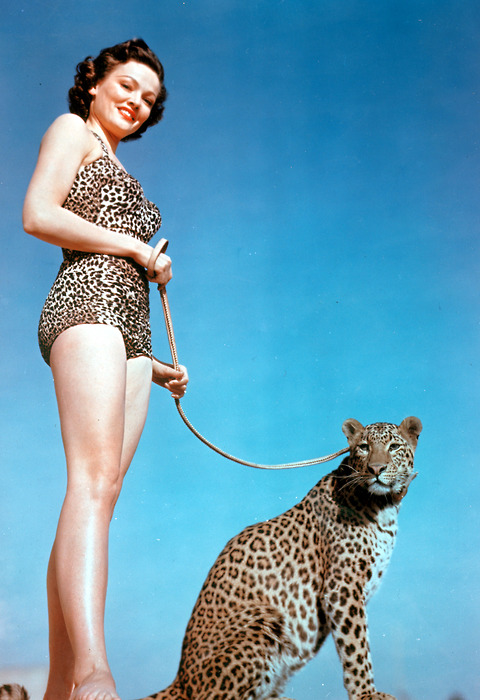

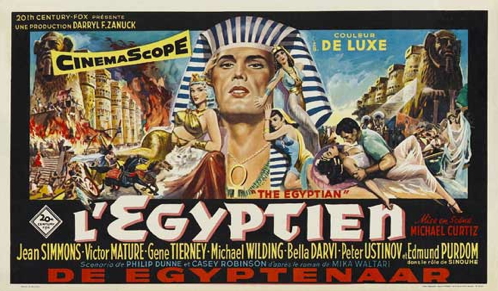

The one section of the film that catches some fire is the scene of

Marjorie Penrose (Lana Turner) coming on strong to Arthur Winner (Efrem

Zimbalist, Jr.) in the Victorian “wedding cake” summer house behind his

home in Roylan, the little enclave just outside Brocton where the

professional families live. This is a memorable scene in the book,

persuasively underlined by thunder and lightning, the last heat of

summer in the autumn leaves, and the very beautiful garden building in

which the conversation takes place. The set dressers here, the sound

effects and music, the roll of the fallen leaves, the effective and

dramatic lighting, and the two performances themselves all come

together to evoke the spirit of the book. I guess there is nothing

particularly cinematic to see, neither in the camera movements nor in

the editing. But the technicolor style, with that swirling music, kind

of takes your breath away. For five minutes. I imagine James Gould

Cozzens was pleased with this scene. The message of the scene( if it

could be put into words?): A nice and ordered Georgian garden with a

decorous Victorian summer house, and it's all about to be ruined, by a

love that possesses its demoniacs.

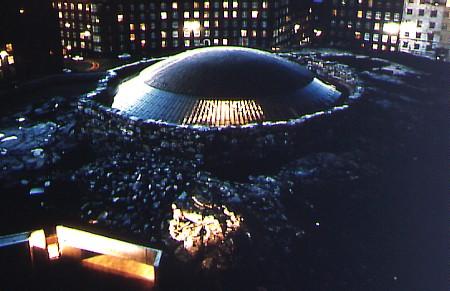

The second and for my money the only other sequence in By Love

Possessed The Movie that works, is the opening credits. They are very

good. Why very good? Because they capture, in just a few expertly

edited exterior shots and one long pan, the emotional, geographical

context of the story, this story of one man's struggle to find the

answer to the question of how and also why it can be possible to live

in the presence of hope. The camera shows two churches around the town

square, one Episcopal, one “mainstream” Protestant; the Court House;

the Union League Club, dying home to the old and increasingly few first

families of Brocton; and a few old and tired 19th Century mansions

still in use. It feels a little like the main square of Columbus,

Ohio, tho' smaller; or the main square of Columbus, Georgia, about the

same size. Then, at the end of the credits, as “Directed by John

Sturges” flickers on, and off, you see Arthur Winner, briskly but not

hurriedly, calmly but not unconcerned, striding, or rather, simply

walking, across that “Brocton Square”.

The credits for By Love Possessed The Movie capture the atmosphere the

book projects. They are the high point of the film.

“Ain't that peculiar? (Peculiar as can be)”: The story is fully

captured in “second unit” work, with not a word spoken nor any

exposition offered.

There is a lot you could say about this. We have a book that is

possibly great — its controversy never diminished its claim, not

self-made, to gravity. By Love Possessed, I repeat, is a grave and

serious book. We also have a movie version that was probably produced

simply and almost only to capitalize financially on the popular success

of the novel. And so the movie tells its story, the best it can,

having to cut the inwardness of the source, the complexity of the plot,

several important characters, and certainly the religious concerns of

the source. (The Episcopal church in Brocton, together with its young

, well educated, and sincere if inexperienced Rector, The Reverend

Whitmore Trowbridge, S. T. D., figures importantly in By Love Possessed;

and Cozzens's depiction of a Sunday service of Morning Prayer is

absolutely the last word in clinical portraits of what they are

actually like. I know what they are like.) There is nothing

controversial in the movie version — no anti-Catholicism, no “Uncle

Toms”, no intolerant remarks about New York lawyers from the failing,

unsteady patriarch Noah Tuttle, none of that! Only the references to

sex have been kept, but even there, oddly enough, the better sex is in

the book and describes a happily married couple making love.

Here I close. Let me confess something. I love this movie! It's not

very good; it is actually boring; the camera set-ups and pacing are

perfunctory; the actors sleep-walk through their parts, with the

exception of Efrem Zimbalist, Jr., who does convey the vulnerable

actuality of Arthur Winner; and the conclusion is rushed and overly

happy. (The ending of the book is hopeful, but not happy.) Yet I love

this movie.

Why? Because it connects in visual form with some of the constructions

my imagination had made on the basis of the words. The town, the lead

character, the meeting by night in the summer house, the gushing,

oceanic music — these are there, right up in front of you.

If Orson Welles had made this, it would have been a completely

different result. It would not have been the book at all. Or it would

have really been the book. If John Ford had made it . . . well, John Ford never would have made it.

As it is, we have John Sturges's big but little piece of work. Although

I will probably keep the novel with me until the day I die, and though

I make no claims for the turgid tired movie it spun off, I will probably still keep the movie under my pillow, for the next six months.