David Cromer's Off-Broadway production of Our Town, at the Barrow Street Theatre in Manhattan, has been getting lots of press attention and some extraordinary reviews. Frank Rich in The New York Times devoted a very insightful column to it, relating the play and this production to the profound crisis of spirit currently afflicting the nation.

mardecortesbaja is happy to offer this equally insightful report on the production by Paul Zahl, who was lucky enough to see it last week. Cromer's staging ends with a startling coup de theatre which Paul discusses in his report and which you might not want to know about if you're planning to see the show, so I've segregated that passage on a separate linked page.

If you weren't planning to see the show, and if you're within striking distance of New York City, I think Paul's report, and Rich's thoughts, might get you to reconsider:

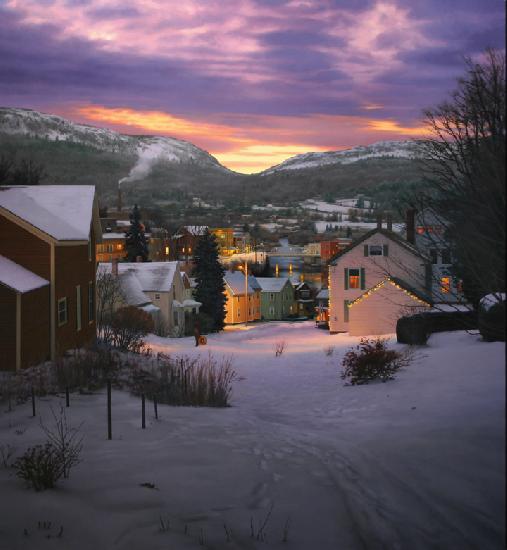

[Image©Scott Prior]

PILGRIMAGE

by Paul Zahl

Wednesday afternoon I took the Vamoose bus from Bethesda, Maryland to the Port

Authority in Manhattan and arrived basically in time to take the subway down to

Christopher Street for the 7:30 performance of Our Town at the Barrow Street Theatre. It was a pilgrimage for me, because I am

influenced just now by the wisdom of Thornton Wilder (below) and had heard a

lot about this particular production.

Charles Isherwood had written in The New York Times of a “. . . surprise Mr.

Cromer springs — a beautiful feat of stagecraft

that transmits the essence of Wilder's philosophy with an overwhelming

sensory immediacy.”

Terry Teachout had written in The Wall Street Journal, “I don't use

the word 'genius' casually, but Mr. Cromer may fill the bill.”

Moreover, Tappan Wilder, Thornton Wilder's literary executor who is a

friend here in the Washington area, had blessed the production. 'Tappy' has seen almost every

production there is or ever shall be.

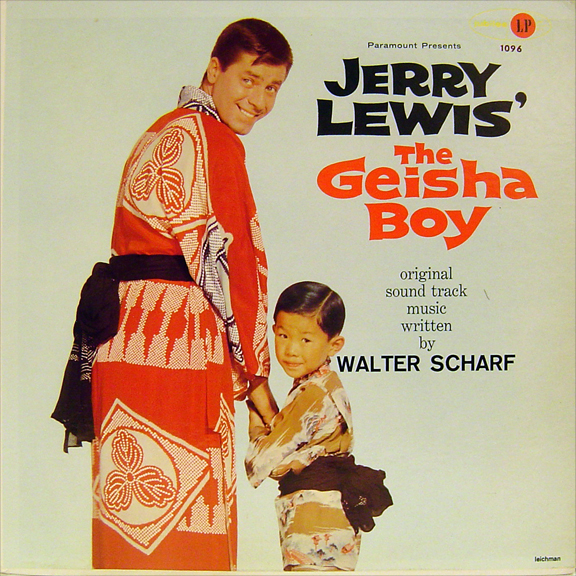

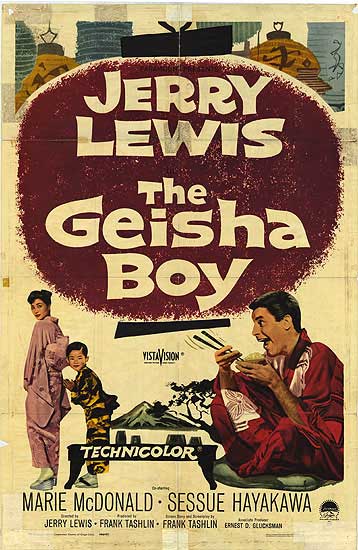

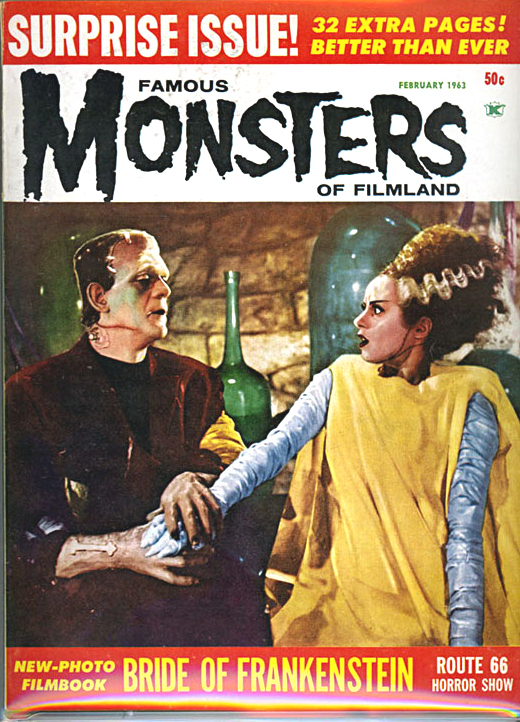

So . . . a brief stop by a West Village video store that specializes in

movies like From Hell It Came and The Black Sleep (which has the

only discussion of the difference between Presbyterianism and

Anglicanism to occur in a 1950s “B” horror movie — no kidding) and then

straight into the theater.

I don't want to talk about the initial staging — in which the actors are

set within the audience, in and through the side and transverse aisles,

and at one point are even asked to read lines of the play. I had seen

this before.

But I would like to reflect on the meaning of the play, as a pilgrimage

to me, which the staging finally makes possible. Act One of Our Town

is full of the gossip and interplay of the people of Grovers Corners,

New Hampshire. It presents two families, the Webbs and the Gibbses, as

they are in mid-career, going about their business with what we today

call “decency”, love for one's immediate family, and some elements of

Christian sympathy. The “theme song” of the play is established in Wilder's use of

the hymn, “Blest be the tie that binds/Our hearts in Christian love”.

There is also a tragic character, Mr. Stimson, the defeated alcoholic

choirmaster of the First Congregational Church.

Director David Cromer ups the emotion of Act One by universalizing

the characters through their everyday 2009 casual clothing and by

getting the actors to show their inward lives through concentrated

facial expressions and some intense action in pantomime. Thus Mrs.

Webb and Mrs. Gibbs reveal their inner drives through stylized, driven work in their kitchens.

You know you're being gotten to when young George Gibbs breaks down as the result of his

father's oblique and rather mild scolding of his son for neglecting his

chores at home, at the expense of his mother. George goes completely to

pieces with remorse, and it is so like an adolescent boy! What I am

trying to say is that Act One goes for the inward life of the

characters and is not content with the outward words and situations.

There is no sense of our being in the year 1910. We are rather in

2009, with every family's unhappiness and missed opportunities in the

field of love.

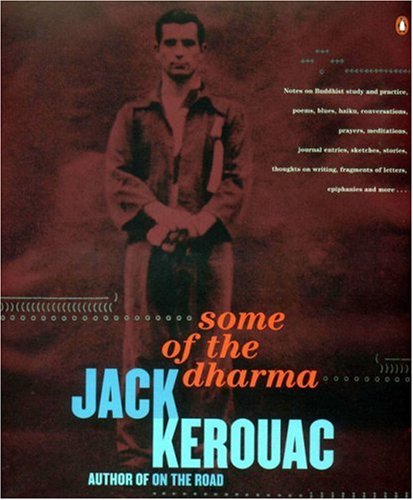

[Image©James Estrin for the NYT]

The text of Act Two goes a big step further as the

inwardness of Emily and George's wedding is brought out in their

tortured recriminations with their parents in the church. It's Wilder

writ large. This is to say that Emily's entrance into the church is

her “inner” entrance, and George and his mother , perfectly portrayed

by Lori Myers, act out his resistance with no mediation between thought

and act. This is absolutely wrenching — the unhappiness and also the

initial nobility of every marriage that has ever taken place. The

blistering Stage Manager, played by Scott Parkinson, 'preaches' here a

little, and that is correct, as he is now playing the Minister. Again,

everyone is in street clothes of the year 2009 so there is nothing

local or 'contextual' to draw the audience away from the universal

situation. If I had any criticism at all of the direction, I would

lodge it only and solely at the conclusion of Act Two, where Mrs.

Soames' comments about happiness are underscored a little too much.

Now for Act Three, the famous Act Three, the Tibetan book of the dead.

I never liked this act, speaking personally, because it seemed too

bleak, as if there were no real or warm heaven. (Note that William

Cameron Menzies, director of the later Invaders from Mars, designed

the canvass of the dead in the Hollywood version of Our Town, with

William Holden and Martha Scott. It is the high point of that film,

the dead standing, not sitting, on an autumn hillside. The hillside

looks like the one Menzies designed for Invaders, and that's an

organic connection in the history of film.)

In any event, I was now beginning to anticipate a “surprise”, about

which all the reviewers had written. I assumed that it would probably

have to do with George's grieving gesture at the end of the Act, which

has been staged in many different ways since the play's first

performance in 1938. Was George going to assume a crucified position

as Alec Guinness did at the end of the original Broadway production of The Cocktail Party, which my mother saw and has never forgotten? Or

might Emily come back from the dead, as she did in the filmed version

of the play — a change that Thornton Wilder himself approved? What

was going to happen?

[Click here to find out what does happen in Cromer's production — those of you who might see it and don't want to be forewarned of the surprise are advised to skip this section and just read Paul's conclusion below.]

I have sometimes said in talks and sermons that psychology explains

everything, and psychology explains nothing. Our Town embodies this

view of life, that the inwardness of the characters explains

everything, that the outwardness of life escapes everyone, and that we

are all actually waiting for a time when, to quote the title of an

early 'compressed play' by Wilder, The Sea Shall Give Up Its Dead.

“And tell me about your identity then, Mrs. Smith,” the Stage Manager says in Act Three.

The Barrow Street Theater production of Our Town, performed in the

late Winter and Spring of 2009, is a religious masterpiece. I wish I

could preach this message. I have tried to do it, and failed almost

completely. I am trying to do so still. It is a theme that can never

be exhausted.

Paul Zahl is a preacher and theologian, and dedicates the above essay to Mary McLean Cappleman.