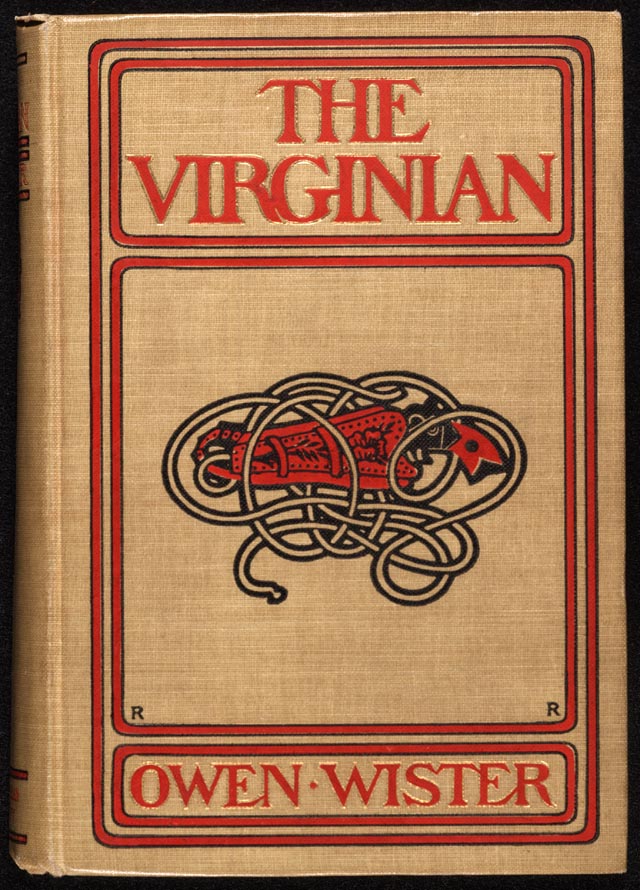

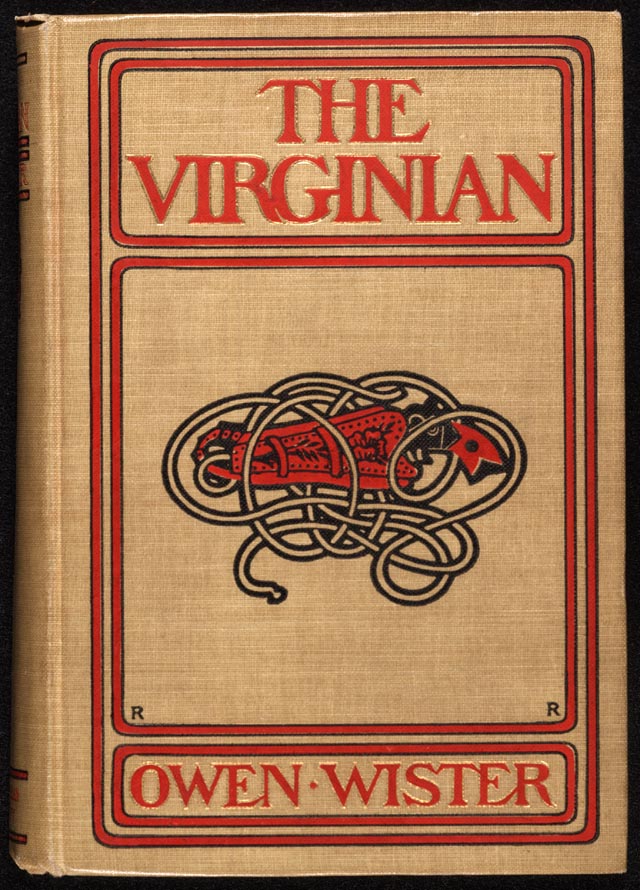

We tend to think that the modern genre of Western fiction began with Owen Wister’s The Virginian, from 1902 — and there’s some truth in the idea. The book was tremendously popular, a publishing phenomenon, and almost single-handedly created a market for novels cast in the same mold. It was a market that, within ten years, the prolific Zane Grey would exploit and expand dramatically.

The Virginian distinguished itself from the dime-novel and lurid stage-play Westerns that had preceded it by its literary qualities — it was a Western that respectable grown-ups could read without embarrassment. Hemingway was a fan of Wister’s work, Wister a fan of Hemingway’s — and they eventually became friends.

The story of The Virginian was skillfully told — the book is still a pretty good read today — and it introduced themes, incidents and character-types that have echoed down through Western fiction ever since, right up to Lonesome Dove. It placed the cowboy or lone gunman at the heart of the Western genre and established his conflict with or taming by civilized society as enduring subjects.

But The Virginian didn’t come out of nowhere, and its lone-hand protagonist wasn’t the only defining element of Western frontier fiction. Clarence King had previously published a popular series of novels about life on frontier Army posts, which would establish its own tradition within Western fiction, and in the Western films of John Ford and other Hollywood directors.

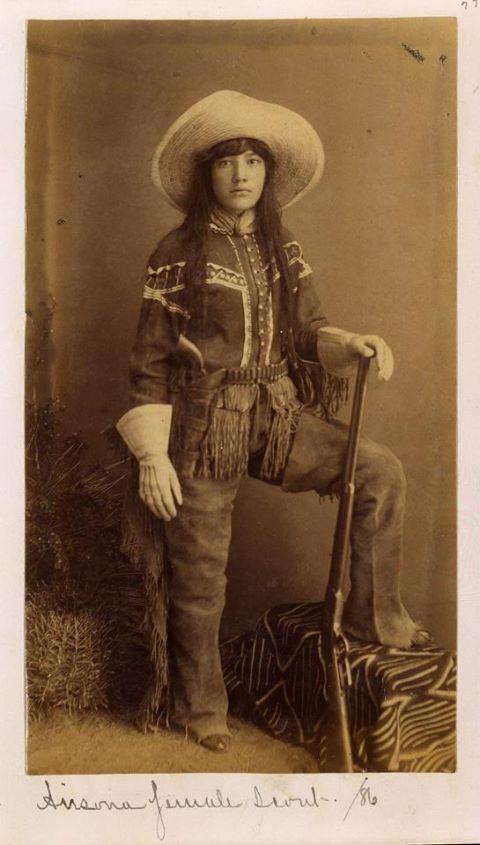

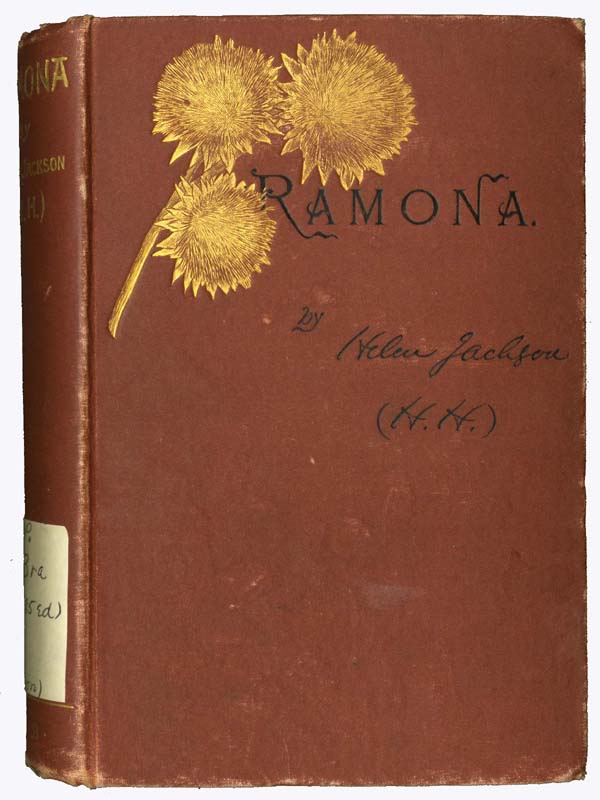

Romances like the popular Ramona, appealing strongly to female readers, had used Western settings before The Virginian — but such novels never established a distinct genre. They were romances first and Westerns only secondarily. There were many other kinds of novels set in the West, dealing with a variety of subjects, which didn’t lead directly into the Western genre.

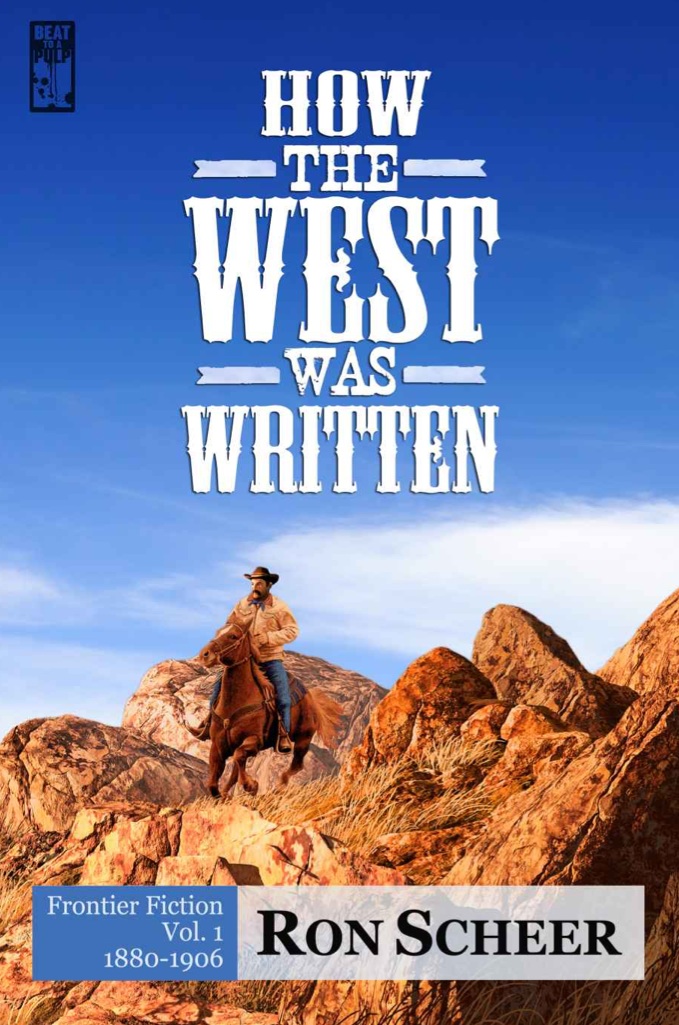

In How the West Was Written, Vol. 1, which covers the years from 1880 to 1906, Ron Scheer offers a lucid and useful survey of American frontier fiction of all types, giving a panoramic view of how the West was treated in novels of the time, in romances, adventures and ultimately in the archetypal, mythic narratives that came to constitute the Western genre as we think of it today.

Scheer’s book is extremely well written, perceptive, illuminating and important. A second volume covering the years 1907 to 1915, has just been published, and I’m really looking forward to it. You can find both books here.