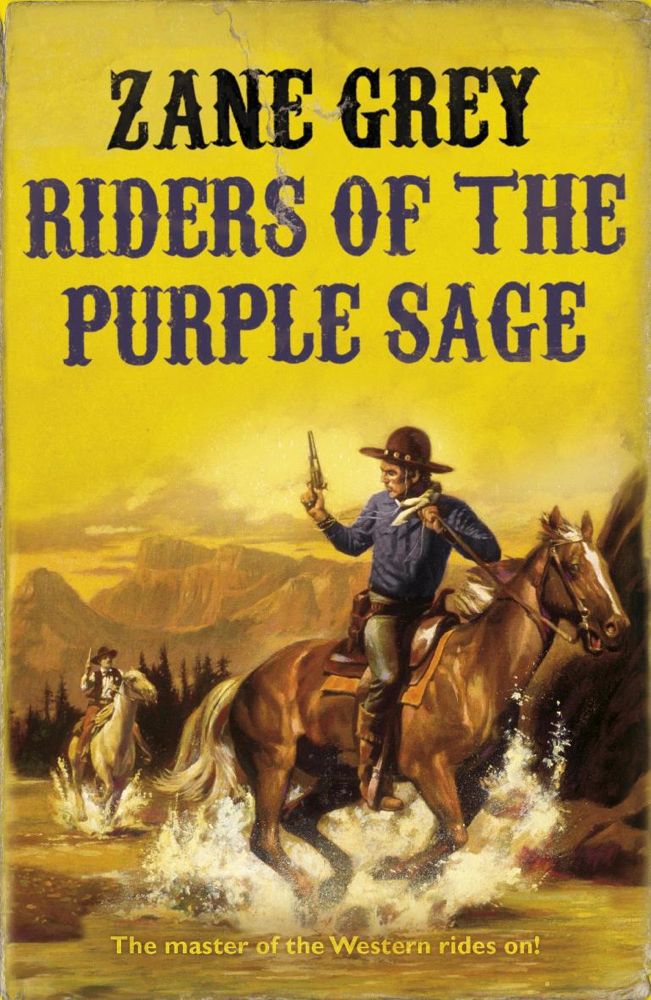

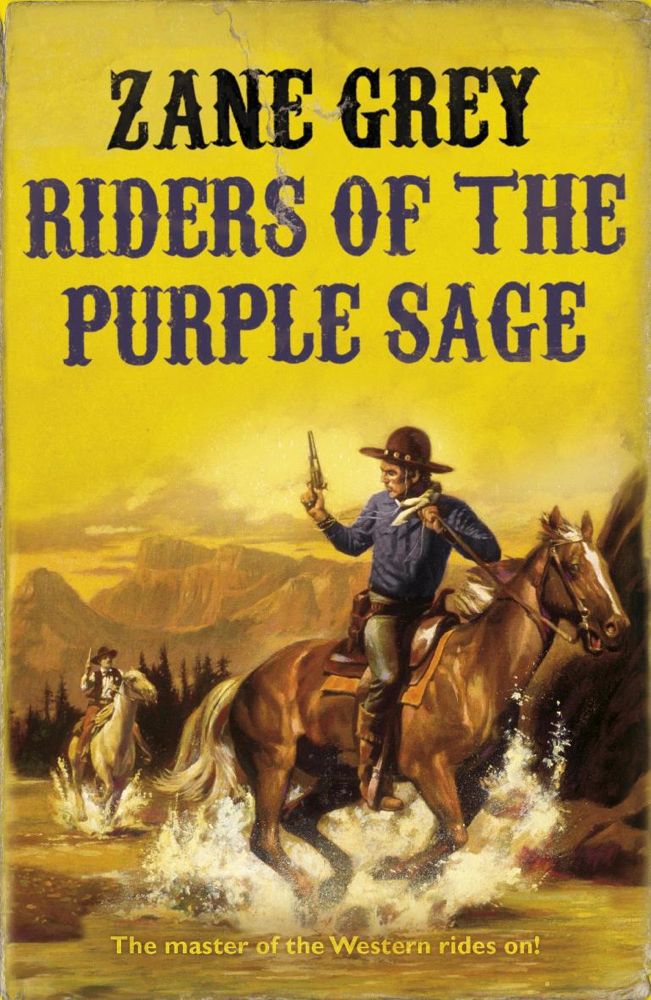

This is the first and only Zane Grey Western I’ve ever read. It was published in 1912. Its prose and some of its dialogue have a creaky Victorian quality, but man, is Grey a good storyteller. In the first chapter he introduces an appealing young woman in a creepy sort of jeopardy, some creepy antagonists and a mysterious stranger who seems to have the power to set things right. A rattling good yarn is off and running.

Grey’s archaic and sometimes clumsy prose is usually employed in the service of an almost mystical vision of Western landscapes — in this case that of southern Utah. The descriptions of landscape don’t read like stage dressing, however, but seem to reflect the author’s powerful personal reactions to places that were still exotic to most American in 1912.

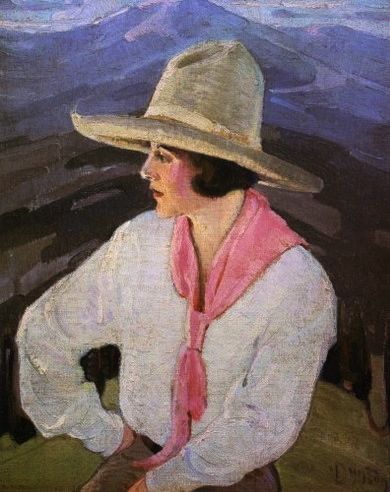

He is telling a tale in which the landscape is a character, one that shapes the human characters in the narrative. He iterates the words “purple” and “sage” repeatedly, like incantations, reminding us of his title, and of his belief that those who ride the purple sage, going about their heroic or nefarious purposes, are not quite like other people. It’s the sort of mystical understanding of the Western landscape that informs the Westerns of John Ford. Grey also spends time delineating the characters of the horses that carry the riders — they, too, become individualized protagonists in the narrative.

And yet for all this literary embroidery, Grey still manages to keep his story moving at a fast clip. His plot involves wicked Mormon elders (Grey apparently nursed a serious grudge against Mormonism), conspiracies with ruthless cattle rustlers, a mysterious canyon where cattle seem to vanish into the earth, a beleaguered but goodhearted and ultimately very powerful Mormon woman, and the unreadable stranger Lassiter, lethal with firearms but bent on some unknown mission, driven by some unknown purpose, that might involve the salvation of the oppressed.

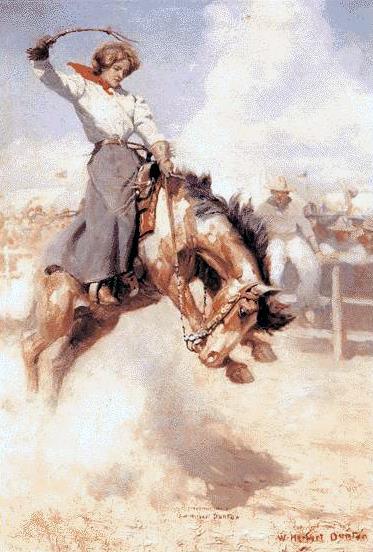

The female characters are particularly interesting — strong, spirited, competent, especially as riders, but with a certain saintliness that the men behold with abject awe. The romantic episodes become in consequence a bit drippy at times — extravagant Victorian paeans to the essence of womanhood. At the same time, the women inspire troubled, rootless men to acts of gallantry and tenderness — a common theme of Western storytelling.

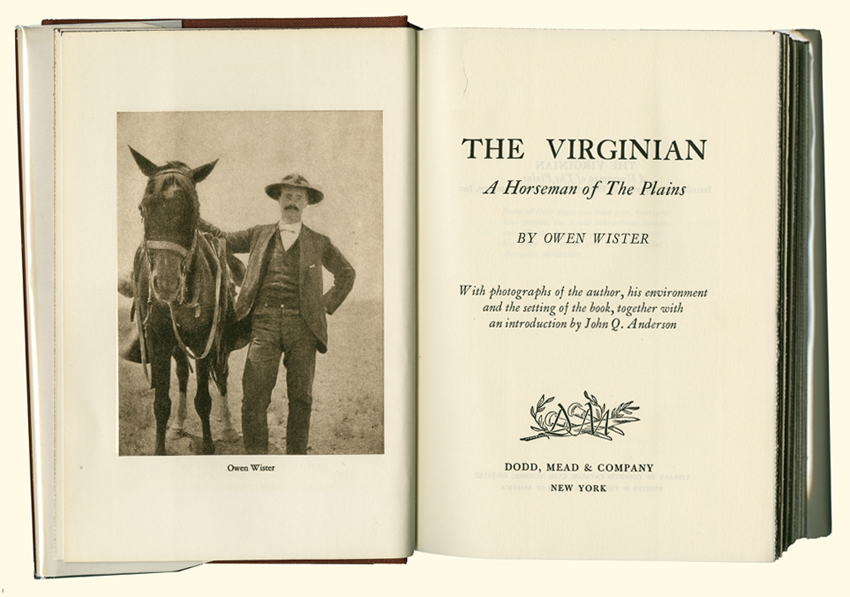

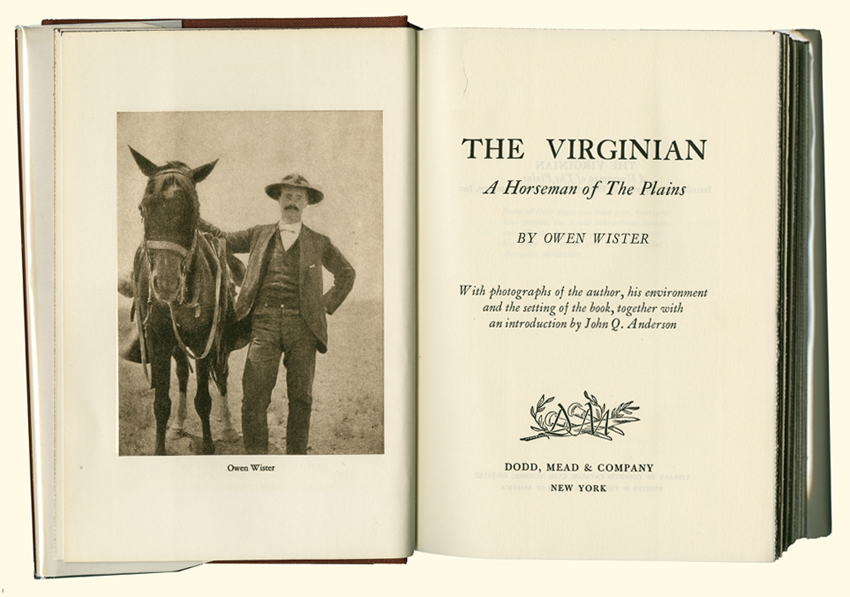

It’s interesting to compare this book with Owen Wister’s seminal Western novel The Virginian, published ten years earlier. The Virginian almost singlehandedly created the market that Grey went on to serve so prolifically. Wister’s prose is less precious, for the most part, less elaborated, and thus feels more modern, but his book is also more episodic — it doesn’t have the narrative drive of Grey’s novel, which imposes a mystery-thriller structure onto many of the Western themes that Wister established.

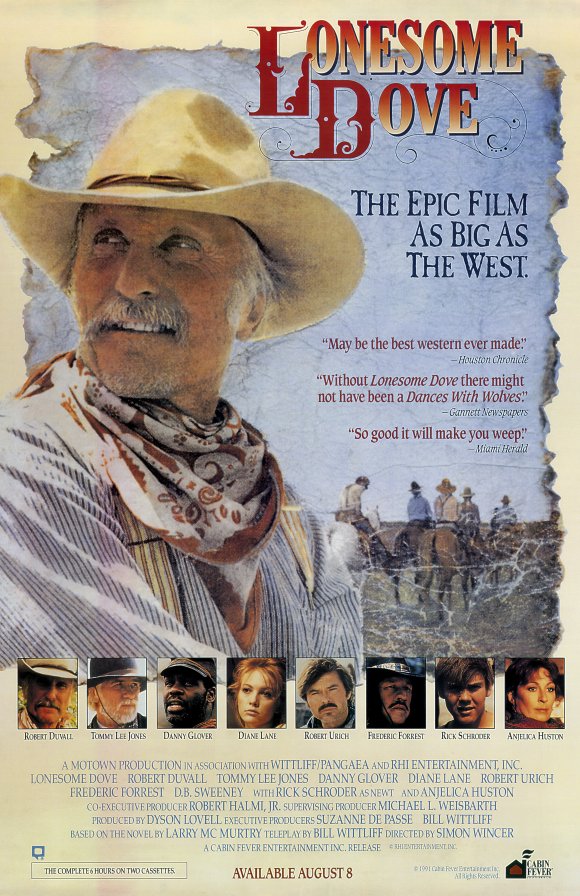

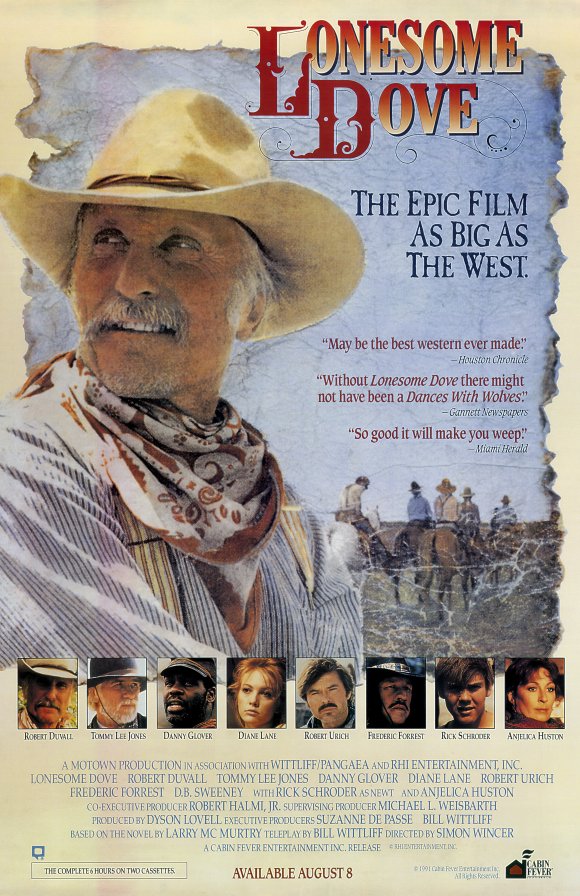

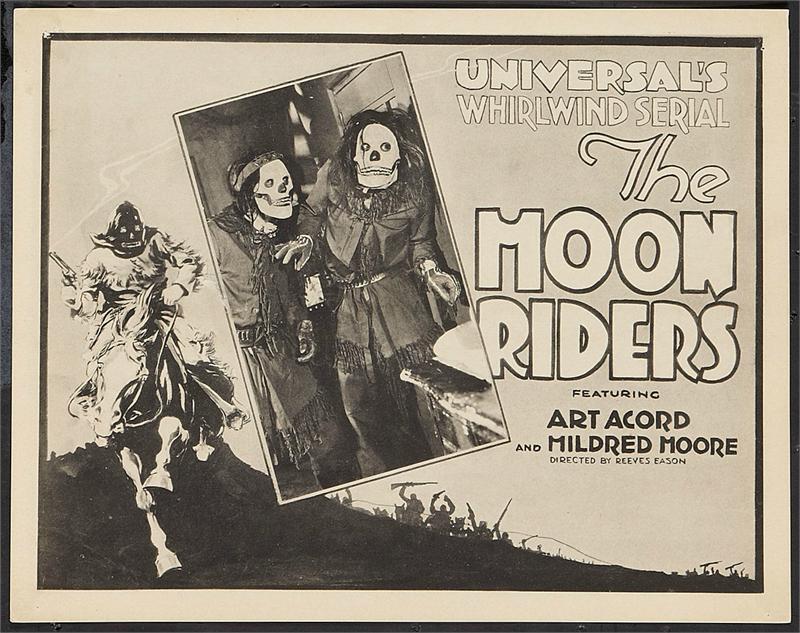

The episodic Western would reach full flower in Larry McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove, but the genre as a whole moved towards more tightly-plotted narratives. It should also be noted that the fabulous elements of Grey’s book would have a strong influence on Western movie serials, in which masked riders, secret conspiracies, hidden caves and canyons figured prominently.

In any case, there’s a compelling pulse of Victorian melodrama in Riders Of the Purple Sage, a momentum grounded in action, with an intriguing mystery thriller at its heart. You can see why the book has remained so popular for so long — one of the cornerstones of Western literature and Western mythology.