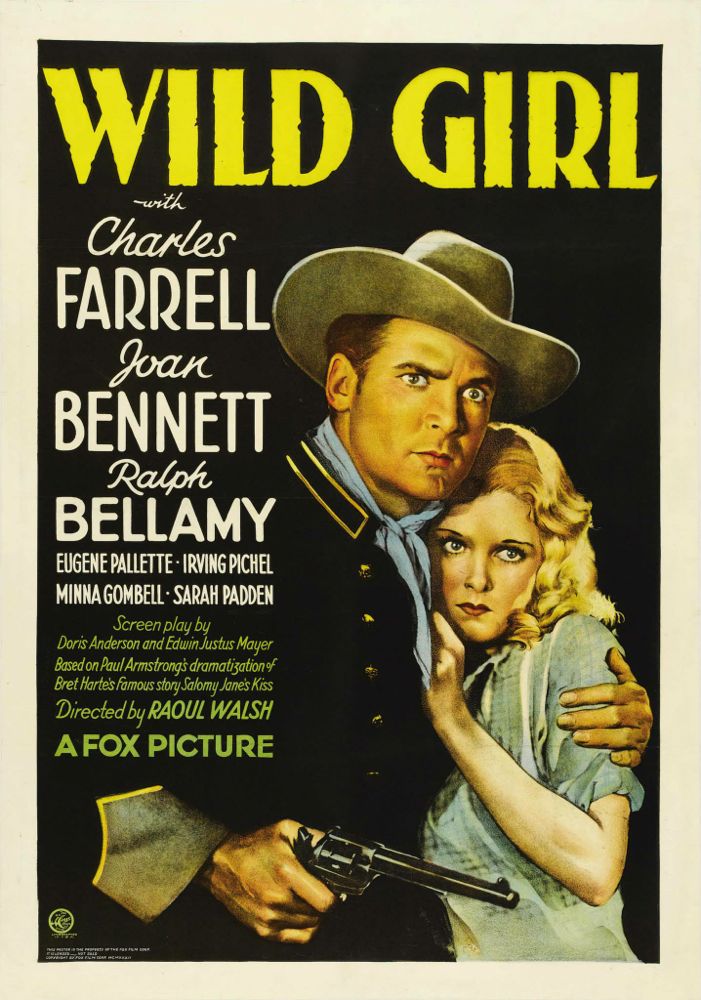

E. L. Doctorow’s first novel, Welcome To Hard Times, published in 1960, was a Western. It was, to be sure, a “literary Western”. Doctorow peppered his prose with passages of fancy-pants writin’ and eccentric punctuation, just to make sure readers knew he wasn’t toiling away in the trenches of mere genre. The villain of the piece was often called only “The Bad Man From Bodie”, capitalized in just that way, associated with a band of “Bad Men” — making it clear that he and they were not just men but mythological embodiments of evil.

Still, the tale starts well, setting up the traditional Western themes of shame, honor and redemption in stark and sometimes powerful ways. As the narrative unfolds, Doctorow loosens up a bit and indulges more and more often in deadpan Western humor and frankly entertaining yarn-spinning. He doesn’t exaggerate his fancy-pants style to the lunatic extremes of Cormac McCarthy’s convoluted gobbledygook, and frequently employs spare and direct language that’s enlivened by quirky insights and supple turns of phrase.

The genesis of the book explains a lot about it. Before he devoted himself to fiction-writing, Doctorow worked for a while as a reader for a motion picture company, in the course of which he plowed his way through many Western scripts. In Welcome To Hard Times, he set out to write a parody Western, but got caught up in his own story and in the tradition and switched to a different strategy — reclaiming the Western as a literary genre.

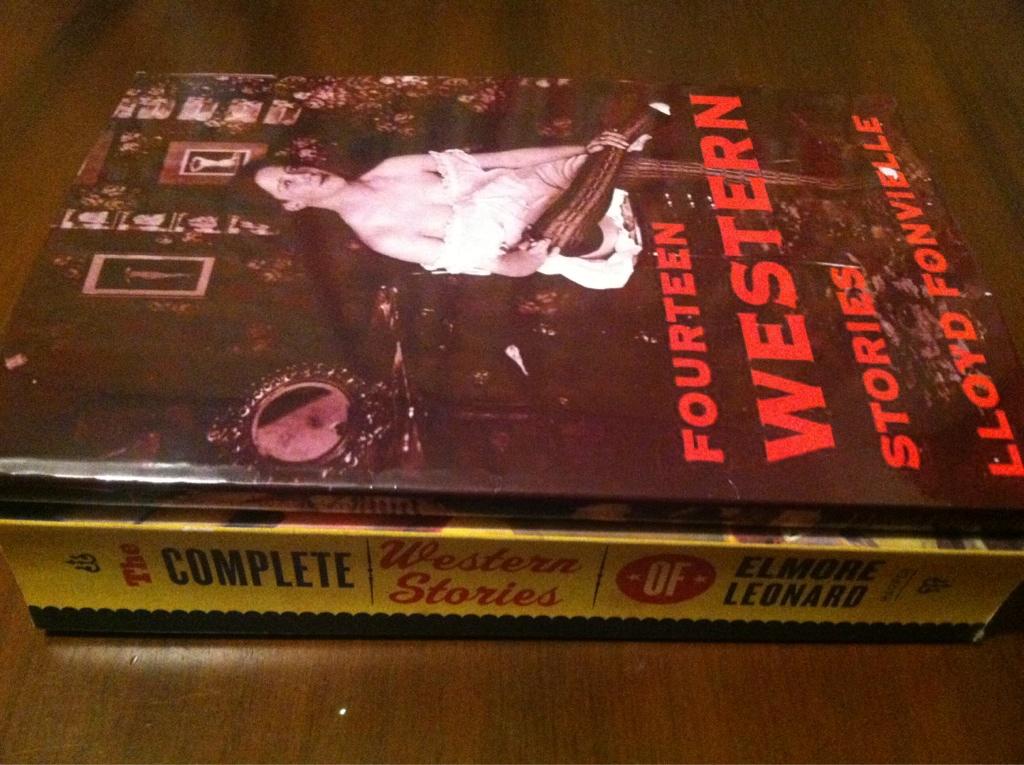

It was a pompous and patronizing ambition. Elmore Leonard, a much greater writer than Doctorow, was still writing Westerns when Doctorow was writing Welcome To Hard Times. The Western didn’t need to be reclaimed for literature as much as it needed to be recognized as literature.

The book’s parodic roots account for the humor of the work, Doctorow’s familiarity with the genre accounts for its mooring in the traditions of the Western, while the author’s sense of being above the genre accounts for the occasional pretentiousness of the style.

Sadly, Doctorow veers disastrously into “literature” at the book’s conclusion, into an apocalyptic and nihilistic climax that wrenches the tale entirely out of the Western genre, mocking the very idea of redemption. What might have been a respectable contribution to Western fiction becomes instead a fairly meaningless and churlish comment on the tradition. It’s the literary equivalent of shooting someone in the back.