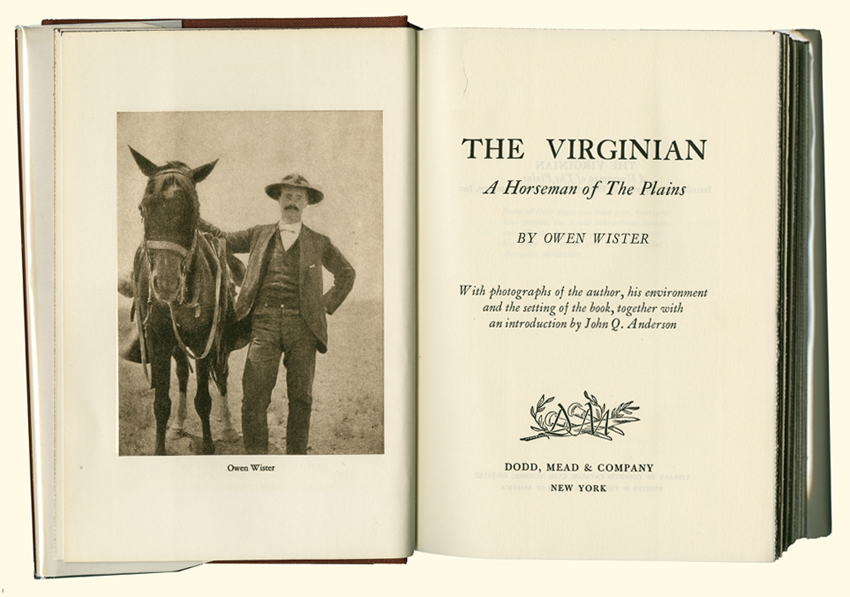

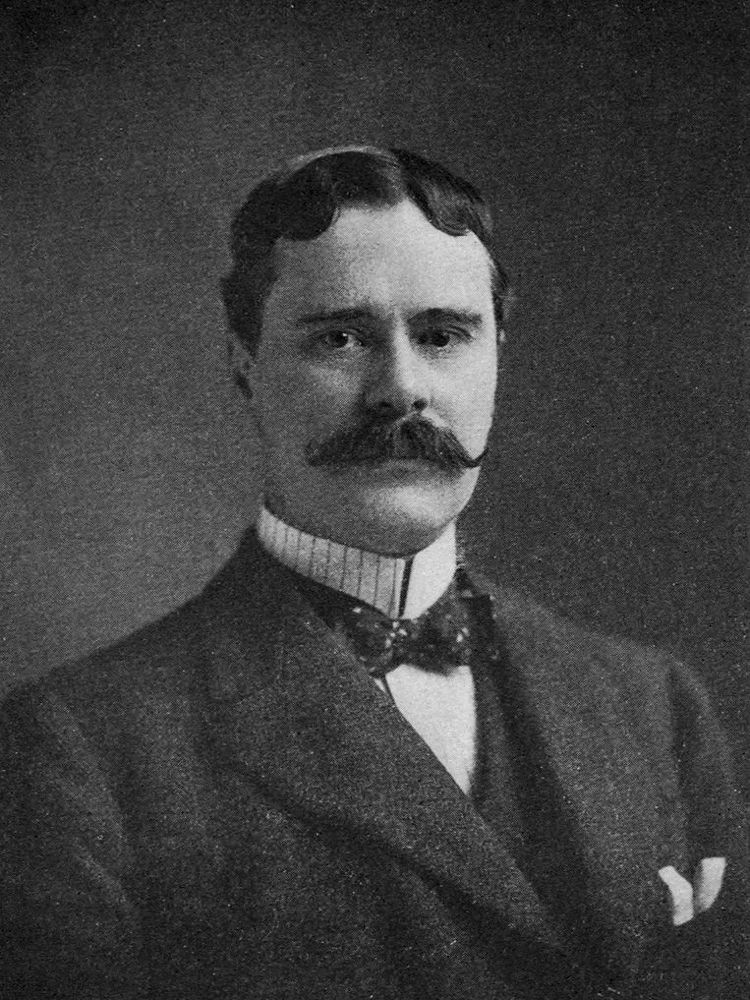

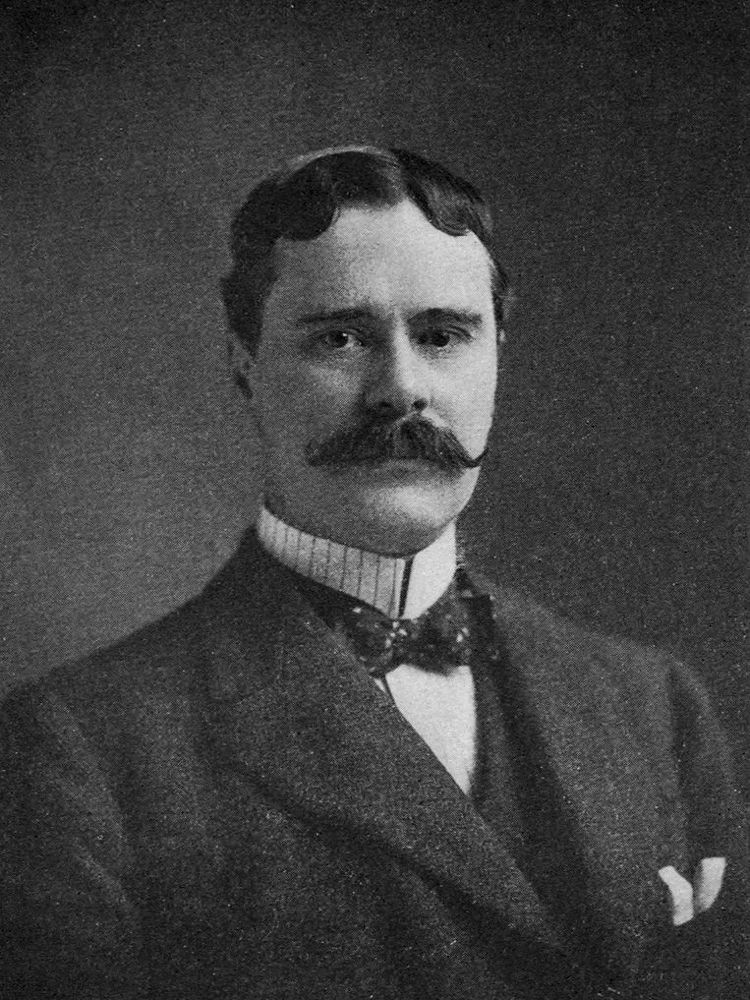

Ernest Hemingway once observed that all modern American literature proceeds from one book, Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn. It could be said with even greater justice that all of what we now call Western fiction proceeds from one book, Owen Wister’s The Virginian.

Western fiction didn’t really exist before The Virginian, at least not as a respectable literary form. You had sensational dime-novel narratives, and you had the frontier cavalry novels of Charles King, but The Virginian created the myth of the cowboy as a kind of knight errant of the plains, as a symbol of noble manhood to be emulated by the increasingly urbanized and emasculated Easterner.

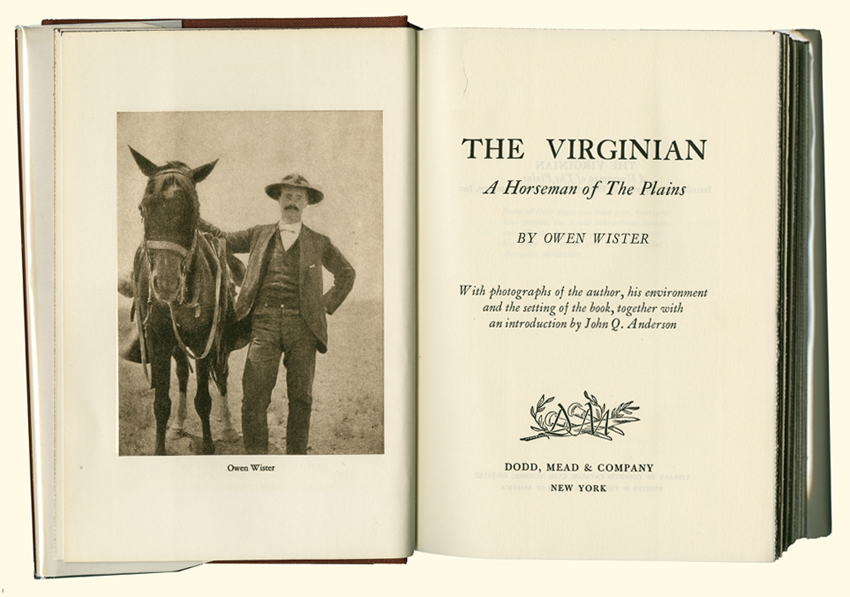

The book, published in 1902, was well received critically and wildly successful commercially — it instantaneously created a genre, and helped define it for generations to come.

Wister’s book introduced the catchphrase “When you call me that, SMILE,” as well as the theme of the Eastern tenderfoot instructed in the virile arts by a true plainsman. It introduced the theme of the Eastern schoolmarm courted and won by that same plainsman, as well as the theme of problematic vigilante justice on the frontier.

The Virginian of the book’s title — his actual name is never given — must at one point hang an old friend who has become a horse thief. The treatment of this is very similar to the treatment of an almost identical incident in Larry McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove.

The plot of the The Virginian revolves around a range war, which would become another staple theme of the Western. Wister based his on the Johnson County War in Wyoming, which also inspired Michael Cimino’s movie Heaven’s Gate, though Wister — perhaps predictably, since he came from Philadelphia aristocracy — took the side of the rich cattle barons, while Cimino depicted them as the villains of the conflict.

The book culminates in a threat directed by the villain at the Virginian to “get out of town by sundown” or face the consequences — meaning a gunfight in the street, which the Virginian must show up for, even though his soon-to-be-bride says she’ll leave him if he does.

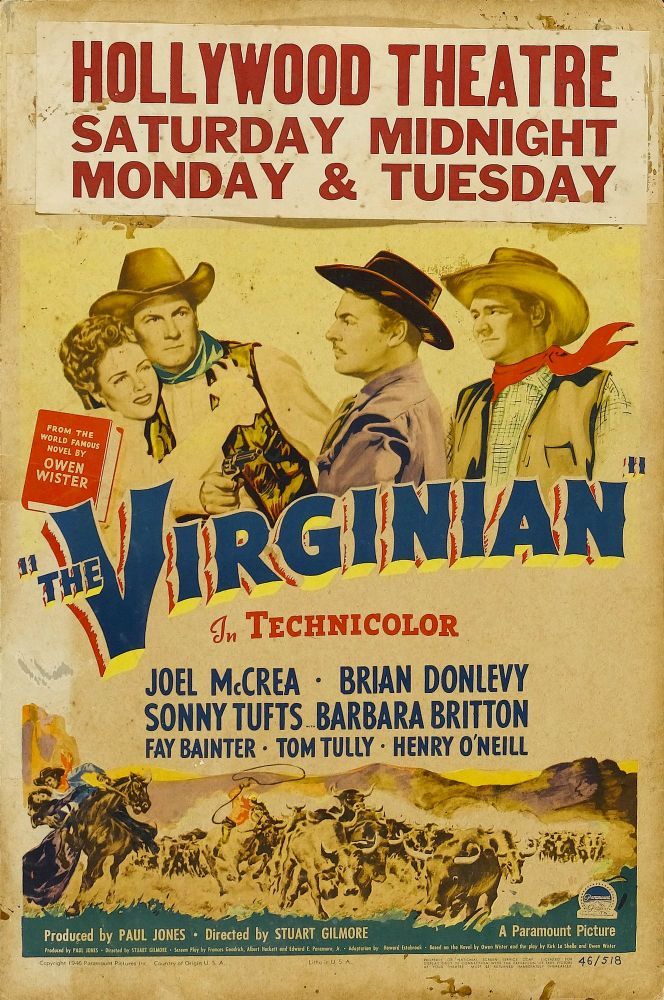

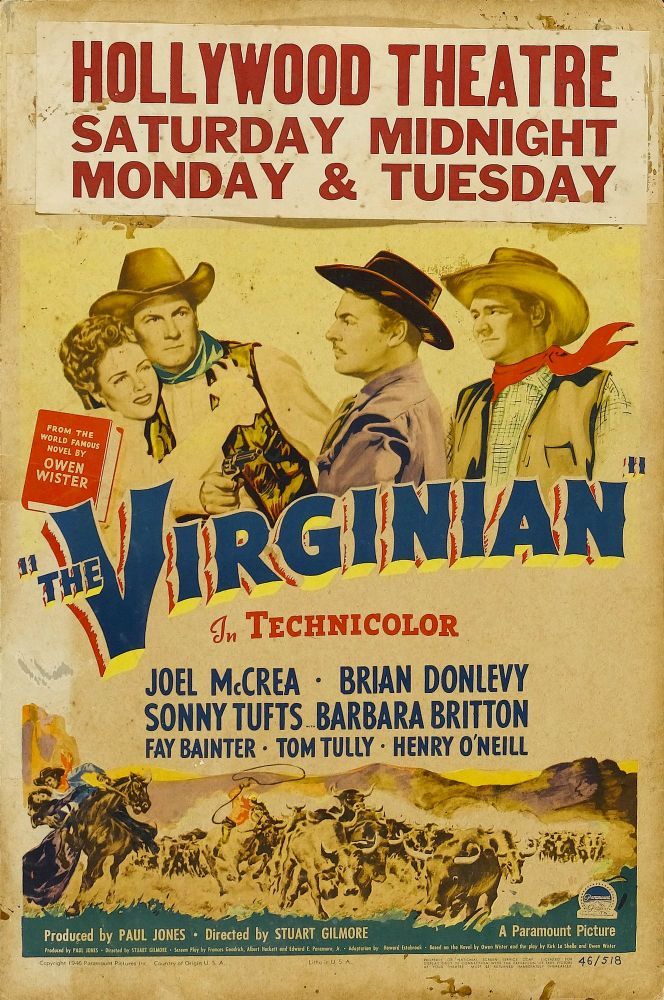

Echoes of the book sound in almost every Western story, on the page and on the screen, created since it was published. (And there have been six movie adaptations of The Virginian itself.) The themes and scenes of the book got reworked again and again in the Western genre.

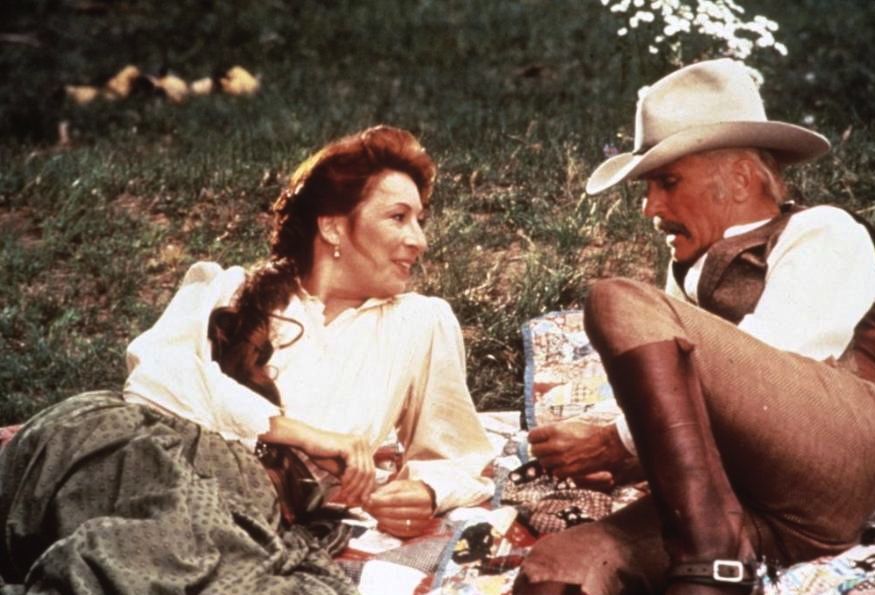

Most curious, perhaps, is that the female protagonist of The Virginian, the schoolmarm already mentioned, is an exceptionally strong character, whose courage and competence are likened to those of a frontiersman. The climax of the courtship comes when she discovers the Virginian in a remote place wounded in an Indian ambush and on the verge of death. He urges her to leave him and seek safety, in case the Indians return, but she simply reloads his pistol and refuses, then gets him back to safety, singlehandedly.

In the character of Molly Woods, Wister was anticipating the strong, active female characters absent from Western fiction for generations after The Virginian — ones that would begin to appear regularly in novels and movie Westerns only in the 1960s and later . . . in Charles Portis’s True Grit, for example, in McMurtry’s Western novels and in Elmore Leonard’s Western tales. More importantly, the love story between Woods and the Virginian is, despite all the other subplots and action sequences, the core of the novel, just as a love story is at the core of McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove.

Wister was hardly an artist equal to Twain, but he was, in his way, just as visionary and influential. He wasn’t even a storyteller in the class of Portis or McMurtry or Leonard — but The Virginian is, in its way, just about as entertaining as any of their Western tales.