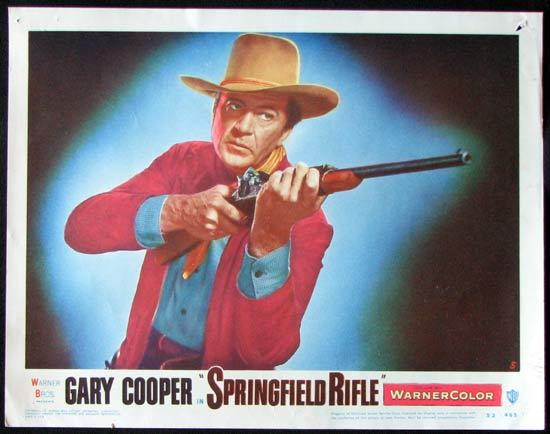

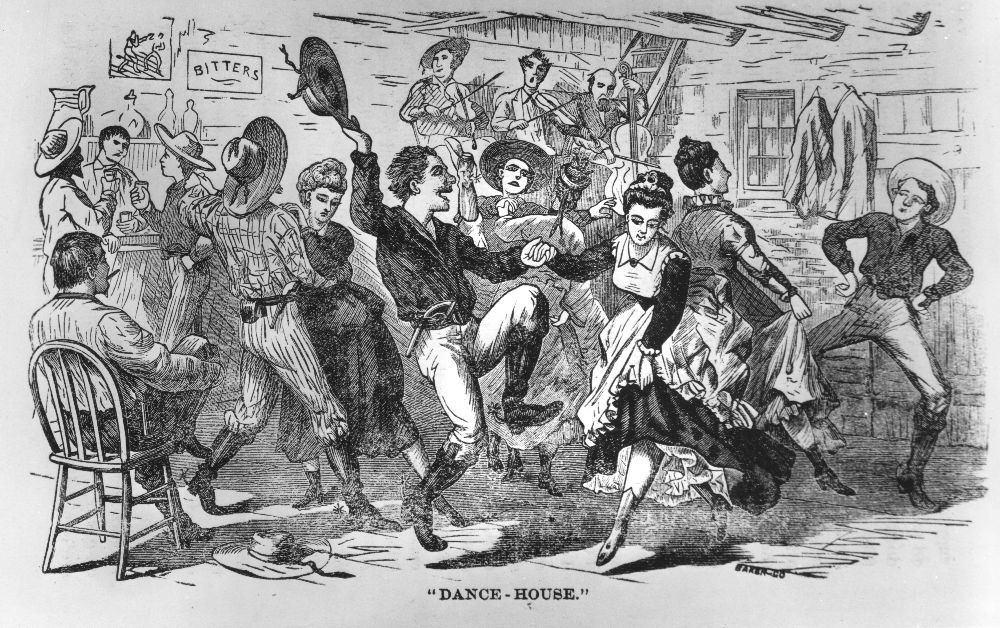

People have often accused Westerns of romanticizing firearms, and there’s truth in the accusation, in the sense that Westerns communicated a respect for firearms and depicted them settling problems. But until the Sixties, Westerns could also be seen as providing instruction in the responsible and even moral use of firearms.

The protagonists of traditional Westerns used firearms only for self-defense or in defense of innocents unable to defend themselves. Transgressing this code identified a man as a villain or as a hero with flaws which had to be redeemed.

Since the Western trafficked in mythology more than in history, the Colt handgun or the Winchester rifle became symbols for any kind of force available to a person, and connected honor and self-worth with using such force thoughtfully and humanely.

All that changed, almost overnight it seemed, with the first scene of Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch. In that scene, the leader of a band of outlaws, played by William Holden, in the course of robbing a bank, takes a group of innocent unarmed people hostage and tells his cohorts, “If they move, kill ’em.”

Holden and his men are the protagonists of the film. The passing of their way of life is mourned in lyrical terms and they die heroically. They were seen as cool — even though they would have slaughtered their defenseless hostages in the bank in order to further a crime.

To Peckinpah this made them tough, ruthlessly efficient, not wicked, and did not compromise their heroic stature. The commercial success of The Wild Bunch confirmed this attitude as acceptable to many but marked the beginning of the end of the Western, by robbing it of its once-central goal of presenting models of potent but admirable manhood. By beginning the destruction of the traditional Western mythology, presenting a more “realistic” portrait of the American past, The Wild Bunch blocked off one avenue of improving the American future.