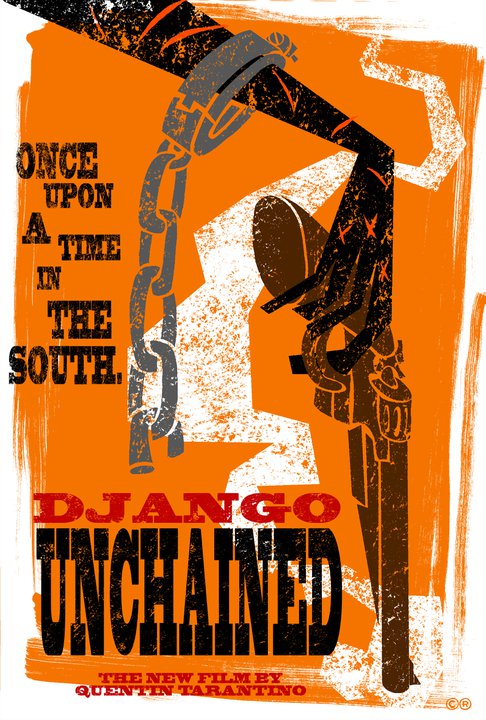

One of the coolest movie posters in decades, even if it is just a teaser.

Category Archives: The West

DJANGO UNCHAINED TRAILER

I’m kind of excited about this.

The first three shots in the trailer were made in Lone Pine, California, where Barbara Stanwyck’s ashes were scattered and where Budd Boetticher shot most of the Westerns he made with Randolph Scott. In short, it’s sacred ground.

A MOVIE PROGRAM COVER FOR TODAY

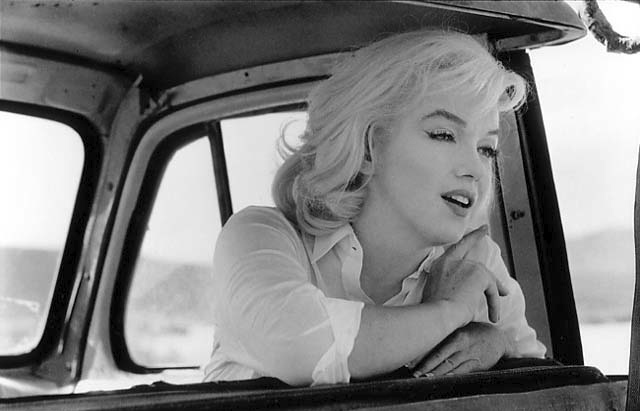

MISFIT

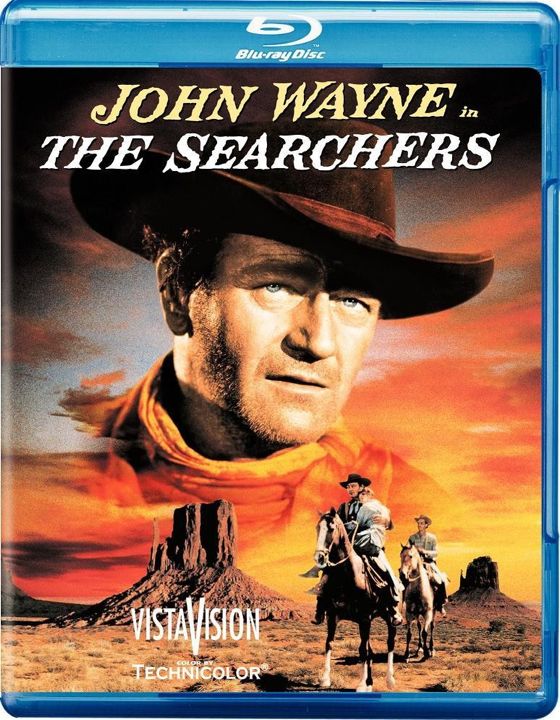

ESSENTIAL

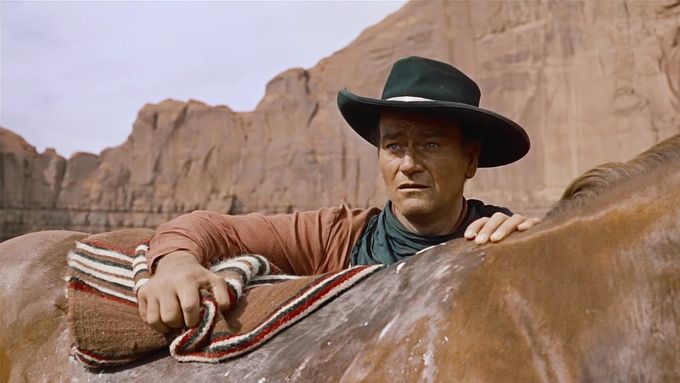

No civilized home should be without this stunning Blu-ray edition of The Seachers and the means to play it on a large-screen television. It’s as close as you will probably ever get, these days, to seeing a pristine Technicolor print projected in a theater — which is to say as close as you will probably ever get to one of the greatest works of art created in America and one of the greatest performances (by Wayne) ever committed to film.

THE SEARCHERS

We will probably never again, in our lifetimes, see a movie like The Searchers. It was made by grown men. They may not have been the best of men, but they were real men, and such creatures are no longer welcome in Hollywood. If a grown man wandered by mistake into Hollywood today he would be hunted down like a dog by the pussies who run the place and ridden out of town on a rail, to the accompaniment of high-pitched hysterical screams.

There are of course real men hiding out in Hollywood in 2012 but they keep a low profile and dream of escaping. They are relics of a vanished time.

This is all just a way of saying that Hollywood has become a place of terminally arrested adolecence and as such is doomed, will pass away shortly into nothing. To quote The Searchers, “Maybe it needs our bones in the ground before that time can come,” but that’s what our bones are for — to mark the fight against what’s pathetic and shameful.

And don’t mistake me — the virility of The Searchers is not about guns and horses and action and moving through wide open spaces. The widest open space in the film is the emptiness inside Ethan Edward’s heart, and inside the heart of the woman he loves, and who loves him, his brother’s wife Martha.

Ethan doesn’t become a real man until he can look into that abyss with clear eyes and live with it. It costs him everything — costs him all his pride and self-regard, his construction of himself as a tough guy. He becomes a man when he’s ready to pay that price. This is something only a man who’s paid that price, or knows he needs to pay that price, understands.

COWBOY GIRL

WHERE BARBARA WENT

When she died in 1990, Barbara Stanwyck was cremated and her ashes were spread, at her request, in Lone Pine, California, reportedly because she had enjoyed making Westerns there.

The Violent Men (above) is the only Stanwyck Western I can track down that was shot in Lone Pine — there may have been others.

Lone Pine is haunted by many movie ghosts, because a lot of movies have been made in the beautiful country around it. I felt their presence when I visited the place for the first time two years ago, but I didn't know then that Stanwyck was literally there, in the dust among the rocks, in the wind. I need to go back now, and take some flowers.

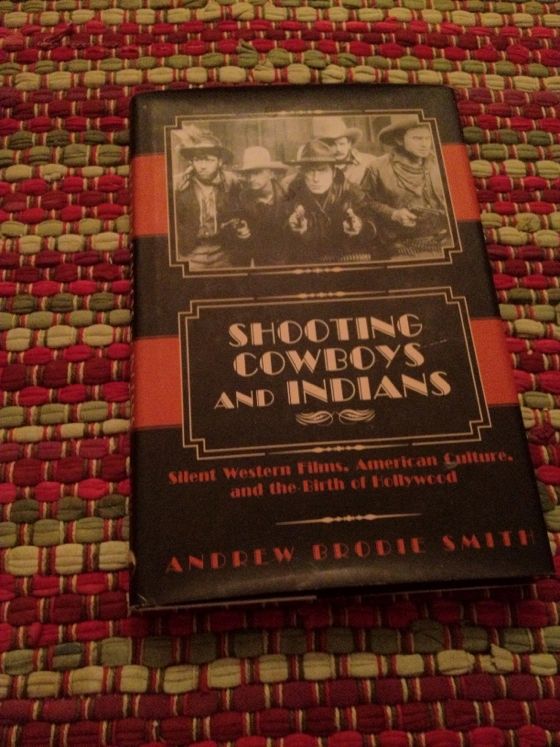

SHOOTING COWBOYS AND INDANS

Although the first truly important narrative film made in America, The Great Train Robbery from 1903, was a Western of sorts, it took about five years before the Western-themed film resolved itself into a recognizable genre. It was a wild and wooly ride, which the form almost didn't survive. Like The Great Train Robbery, early Westerns focused on violent crimes. They modeled themselves on sensational Western dime novels and appealed mostly to kids and male working-class moviegoers — and to foreign audiences. When producers and distributors decided to court a higher class of clientele, including women, the Western came to seem unsavory, driving the better sort of folk away from the fancy new movie palaces that were gradually supplanting the storefront nickelodeon.

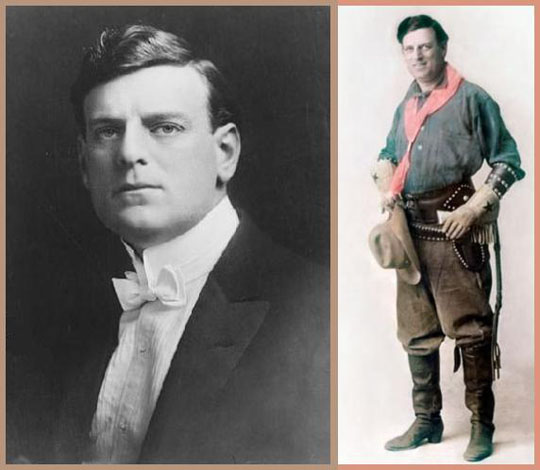

Gilbert “Bronco Billy” Anderson (above), who had played three bit parts in The Great Train Robbery, rode to the rescue by creating a Western hero who appealed to all classes and to women. “Bronco Billy” might start off as a bad man but his heart was always in the right place and he always ended up tamed by and defending conservative social values, usually personified by a beautiful and virtuous woman.

When Anderson lost interest in Westerns, and movies in general — his dream was to become a theatrical impresario — William S. Hart (above) was there to fill his boots. Hart played a tougher and more taciturn Western hero but like Anderson always came around to the defense of traditional values, religion and social order.

In the 1920s, an era of industry consolidation, the studios generally gave up on Westerns that might appeal to everyone. The B-Western was born, marketed once again to kids, to working-class males and to foreign audiences. These constituted a reliable though limited base for Westerns, which had to be cheap and formulaic to make money — but they made a lot of money on that basis and were a major source of studio profits. They produced big stars like Tom Mix, above, but stayed lean and mean where budgets were concerned.

The wonderful book by Andrew Brodie Smith pictured at the head of this post tells the tale of how the Western was born and how it evolved into a genre — restricted in form by the 1920s but still vital and immensely valuable to the industry. Well-researched and written, it's essential to understanding the role and nature of Westerns in the earliest years of cinema.

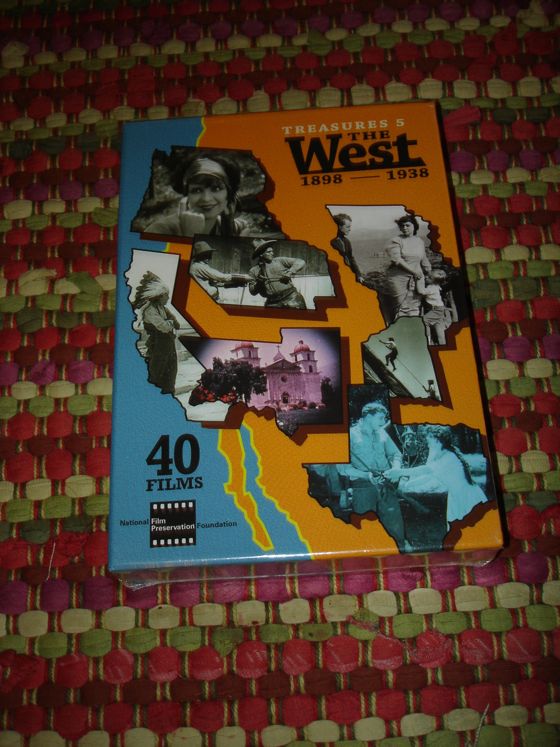

TREASURES WEST

You can't imagine how excited I am about this . . .

SHAME AND HONOR IN THE WESTERN

Facebook friend Ray Sawhill has a theory that classic Westerns deal with the themes of shame and honor, which began to feel old-hat in the Sixties when movies shifted more and more to the paradigm of guilt and therapy, following trends in the culture at large.

This wasn’t a universal trend, however — even though it came

to dominate Hollywood (which still has a strong culture of guilt and

therapy) as well as various other self-styled cultural elites — because

whenever a Western dealing with the themes of shame and honor has

managed to slip past the Hollywood gatekeepers, it has invariably found

a big audience. See Unforgiven and the new True Grit, for example.

As I see it, the difference between shame and guilt in this context would be — shame is something you feel because of your own failings, while guilt can be seen as something imposed on you unfairly by others. The difference between honor and therapy would be — honor requires you to make moral choices and take moral actions, while therapy can be seen as something you pay for with cash and consume passively, without the intervention of moral thought.

Therapy strives for vindication and healing — honor strives for redemption, and redemption is the theme of almost every great Western.

You have to have unusual power and authority in Hollywood to get a shame-and-honor Western made, you have to be Clint Eastwood or the Coen brothers, because the industry simply doesn’t understand such movies, and to the degree that it does understand them, it hates them, even when they make a lot of money — perhaps especially when they make a lot of money. If there ever is a full-scale revival of the traditional Western, it will have to originate outside of Hollywood.

BONNIE McCARROLL

Bonnie McCarroll, female rodeo rider from the early half of the last century, is famous for two things. The first is the amazing photograph above, taken in 1915 when she was thrown from a bucking bronco — and not badly hurt. The second is her death fourteen years later from a very similar accident.

In the old days lady bronco riders used to tie their stirrups together under the horse's belly for greater stability. On her fatal ride, Bonnie's horse leaped up then plunged to the ground in a kind of somersault, slamming Bonnie's head against the ground and knocking her unconscious. The horse got up again, with Bonnie still in the saddle, and Bonnie's boot got stuck in one of the tethered stirrups when a fellow rider tried to get her off the horse. Then the horse bolted, knocking Bonnie off and dragging her around the arena with her foot still wedged in the stirrup. She died in the hospital of brain injuries ten days later.

She was thirty-four years-old at the time — a woman of true grit.

SEARCHERS

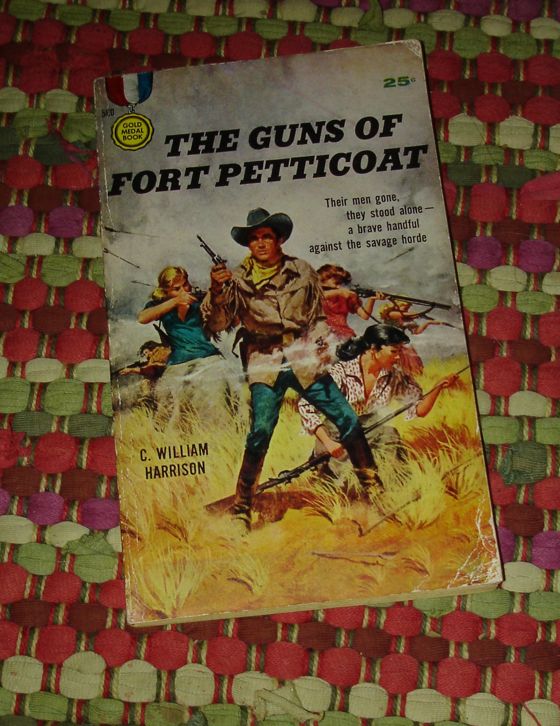

THE GUNS OF FORT PETTICOAT

They had only a few days in which to stave off slaughter — twenty-two women and one man forted up against all the howling hell that would be thrown against this lone, desolate stronghold!

Sounds good.

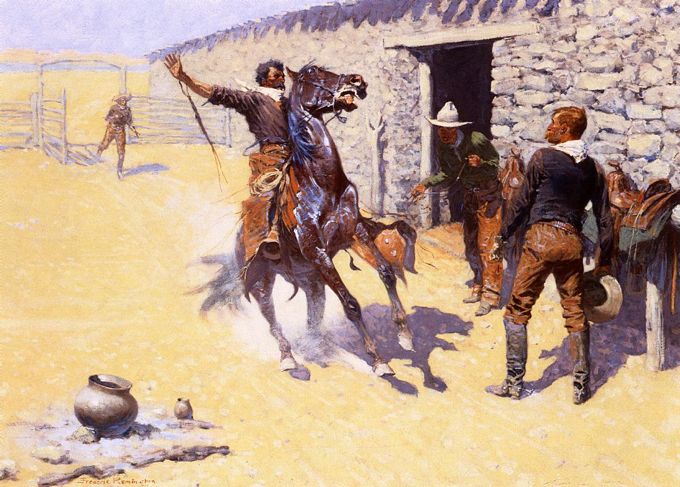

A FREDERIC REMINGTON FOR TODAY

The Apaches! — 1904