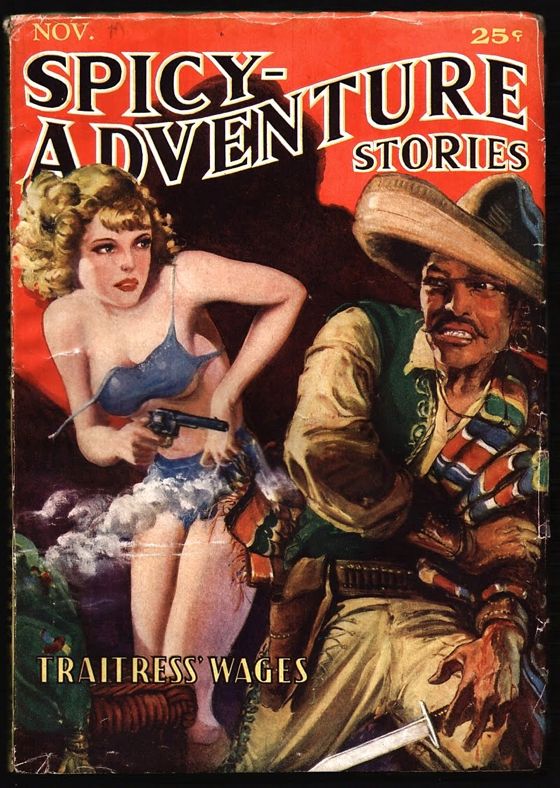

This looks spicy, indeed — from 1935 . . .

This looks spicy, indeed — from 1935 . . .

Directed by John Ford, 1926.

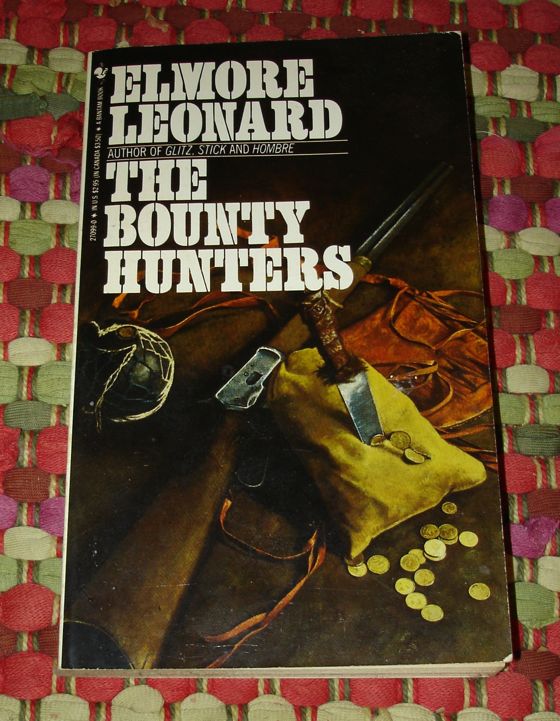

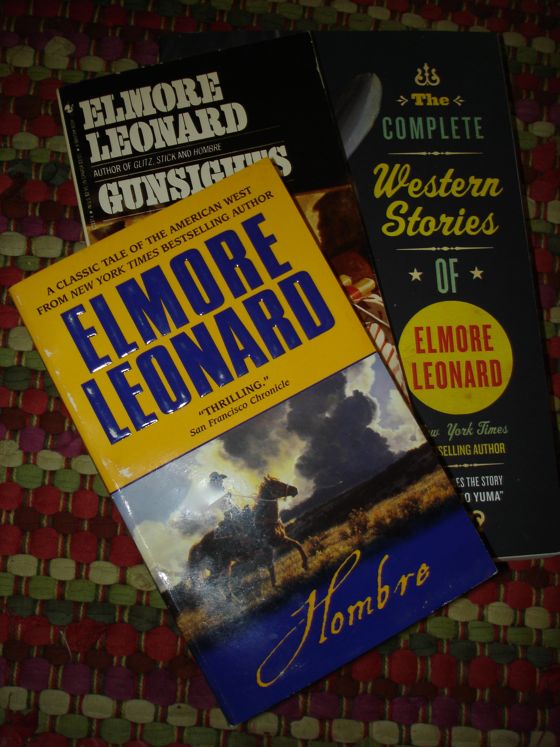

Before he became the best writer of crime thrillers in modern times, and one of the best novelists of modern times, Elmore Leonard wrote Westerns. He started out writing Western short stories for the magazines that used to print such things and then in 1953 he published his first Western novel, The Bounty Hunters, which I just read.

Although it was his first novel in any genre, it possesses most of the virtues of his later works — a taut, suspenseful plot, eccentric characters, startling episodes of violence, creepy villains and a protagonist who's cool but not too virtuous. It's invested with a strong sense of place, in this instance the Arizona Territory and Mexico, and the prose is spare but lively. The story moves.

The tale reworks a lot of familiar Western conventions, as most Westerns do — that's part of the challenge of genre fiction. One can see elements borrowed from Western movies and given a harder, sharper edge.

It's a fine piece of writing and a superbly entertaining read.

I'm going to go back now and read all the short stories Leonard wrote before The Bounty Hunters, and then proceed on to everything he wrote in the Western genre. Having read most of his contemporary thrillers, I feel as though I've discovered a brand new author. There are reports that he's thinking of writing a new Western. I hope it's true, because it would be fascinating to see how he'd approach his first love after achieving mastery and fame with other kinds of material.

Come on, Elmore — let's go to Missouri.

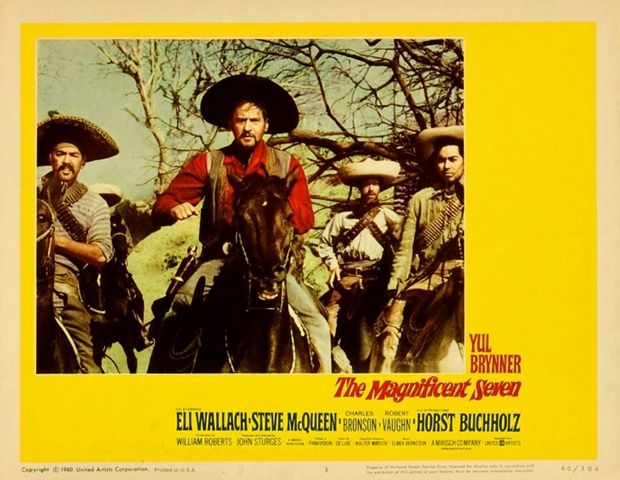

The Magnificent Seven is one of the most entertaining and influential Westerns ever made but it has some problems that keep it from being a great Western and they start with the hats worn by the seven gunslingers, too many of which are small and jaunty. They're TV cowboy hats, Rat Pack cowboy hats. Yul Brynner's is the worst. It's sort of a tiny tricorne, like the one the poet Marianne Moore sometimes wore. On her it looked cute. On Brynner it looks cute. A cowboy's hat should not look cute.

An actor playing a cowboy may not need a hat with a brim wide enough to keep the sun out of his eyes, or with a tall crown to keep his scalp cool, because he doesn't spend all day on horseback under a blazing sun — he has a trailer he can retire to between rides. But the character he's playing should look as though he could spend all day under a blazing sun and have a hat suitable to the activity.

Steve McQueen, Charles Bronson and James Coburn wear hats that are adequately large, barely, but they've rolled the brims up on the sides to convey a kind of hip jauntiness. Hip jauntiness is not a primary cowboy virtue. Still, it's worth pointing out that the three actors who wear more or less acceptable hats all went on to have careers as the stars of memorable action films, including many Westerns, while those who wear hats that aspire to the condition of the modern fedora did not.

When Eli Wallach and his band of Mexican thieves gallop onto the scene, with their grand and authentic-looking sombreros, your first impulse is to root for them in the battle over the beleaguered peasant village, because they wear the hats of men.

In a Western, wearing clothing that at least approximates the style of the period the film is set in has one great advantage — the film has less of a tendency to date. It always looks classic.

Brynner doesn't give a bad performance in The Magnificent Seven, but he doesn't quite inhabit the Western genre. He has a peculiar regal walk which commentators on the film have often drawn attention to — the walk of an actor who has played the king of Siam a few too many times. It doesn't have the natural, fluid grace of a real cowboy's walk, a real horseman's walk. He also has a Russian accent, which the film tries to sell as a Cajun accent — a preposterous ploy that only draws more attention to its anomalous quality.

His silly little hat becomes a symbol of his unconvincing Western persona — inescapable even when he's not talking or walking. A respectable Western hat would have gone a long way towards reconciling us to that exotic persona.

The same is true of the German actor Horst Buchholz, whose German accent the film tries to sell as Mexican. He has the physical grace of a cowboy, and when he dons a big sombrero for a few scenes he actually looks like a cowboy. At all other times his dainty little hat brands him as an impostor.

What were they thinking?

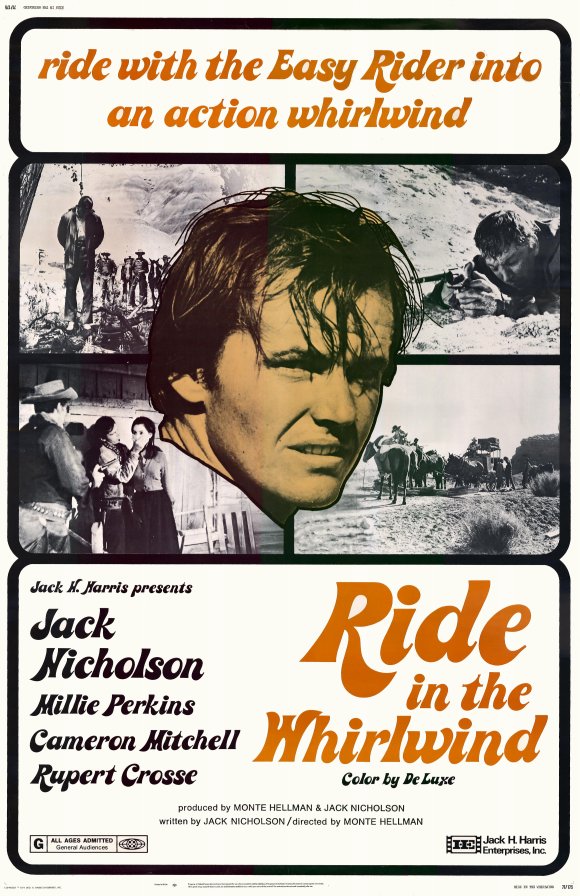

This is a poster from a 1971 re-release of the film, orginally made in 1965. The tag line of course references Easy Rider, released in 1969, which had made Nicholson a marketable personality. The film was financed by Roger Corman and made back-to-back with another Hellman Western, The Shooting, near Kanab, Utah. The films were then sold to a distributor who sold them directly to television. Ride In the Whirlwind was subsequently released theatrically on a couple of occasions and became a huge hit in France, especially among cinéastes there, who have lionized Hellman ever since.

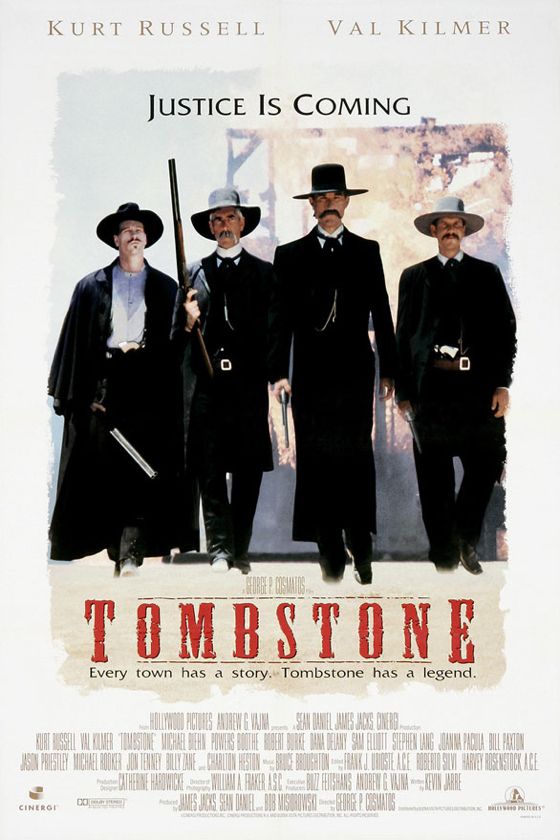

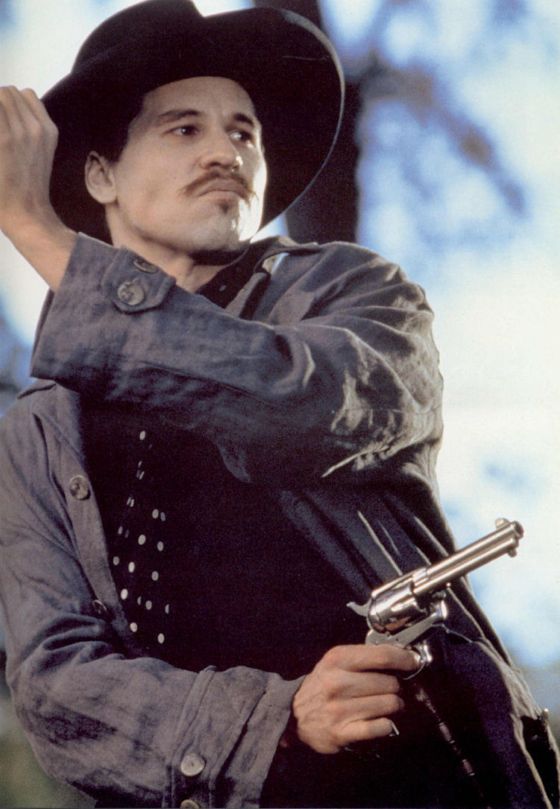

In the wake of my friend Kevin Jarre's recent death, I decided, fearfully, to re-watch the movie that might have been his masterpiece, Tombstone, released in 1993 as “A George P. Cosmatos Film”.

I watched it for the first time, when it came out, in a state of sorrow, but this time I watched it in a state of rage. Then, one could see it as a lost opportunity for cinema, for the Western, and for Kevin. Now that he's gone one has to view it as the last opportunity for Kevin, who had the ability once to resuscitate not just the Hollywood Western, but Hollywood itself.

When I read his original 138-page draft of the script, not long before Kevin went off to start directing the film, I believed I had encountered something momentous. “This movie,” I said to him, “is going to be like Jackson's flank march at the Battle of Chancellorsville.” That march was a recklessly bold move by most of Lee's available forces to strike the rear of the overwhelmingly superior Union forces confronting him. While Jackson was on the move, Lee would be totally vulnerable to even a modest Union advance. If the march had been detected while in progress, Lee's whole army could have been crushed in detail.

It was not detected, it took the Union forces totally by surprise and sent them into a full-on rout. It turned what was a stalemate at best into an impossible victory.

I associated this with the movie Kevin was about to make because I knew that Kevin had conceived of a film which would be both stunning, artistically, and wildly commercial. Hollywood would not know what had hit it. Kevin had revived the craft of storytelling from Hollywood's Golden Age, brought it forward into the modern era and opened a way back into films that were both entertaining and powerful, exhilarating and profound.

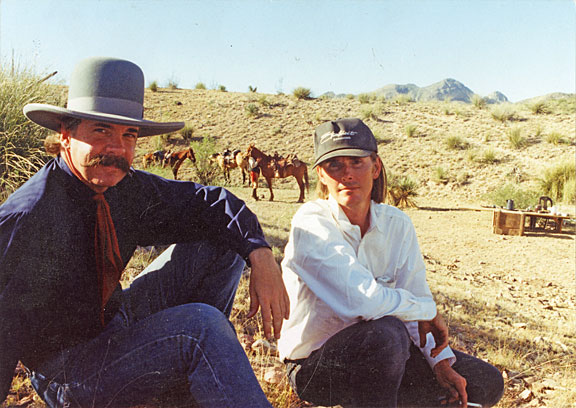

Kevin (above right, on the set) lasted only a few weeks as director of the film. I can't say of my own knowledge why he was replaced. There are stories of eccentric behavior on his part, and of falling behind schedule. I do know that the power on the production shifted to mediocrities, and that they trashed his vision. Enough of it remained to make the film beloved by fans of the Western and a solid hit at the box office, but enough of it remained also to make clear what it could have been.

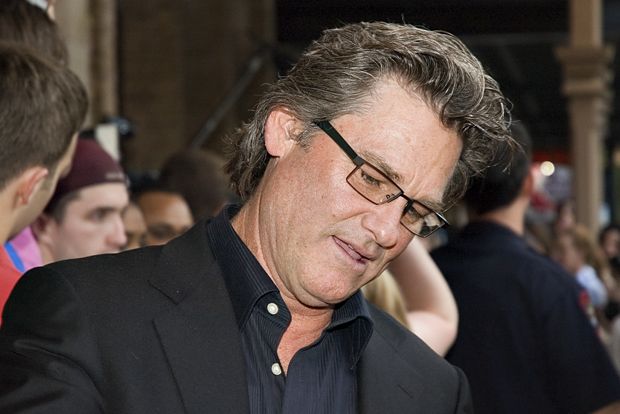

Kevin cast the film, of course, and supervised the design of the production. Every choice he made on those fronts was pitch-perfect. Some of the footage he shot remains in the film, and all of it is breathtaking, worthy of John Ford, a comparison I don't make lightly. The rest of the film looks like crap, like a high-class TV movie. About 30 pages of Kevin's script were discarded, and Kurt Russell and Val Kilmer worked with the director who replaced Kevin, George Cosmatos, and with a journeyman screenwriter named John Fasano to “improve” existing pages.

Everything done after Kevin was fired cheapened and diminished the film. After the film was favorably received by critics and audiences, the mediocrities were proud to take credit for the cheapening and diminishing, as though these things had actually been what “saved” the picture and made it work.

These people didn't just want to take the miraculous gift Kevin had given them — they wanted to pretend that they had given it to themselves.

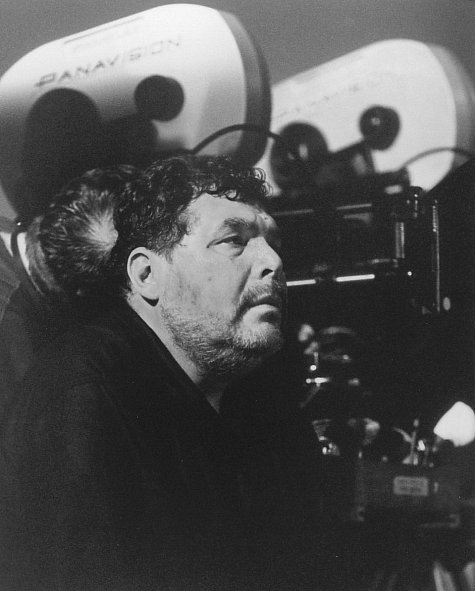

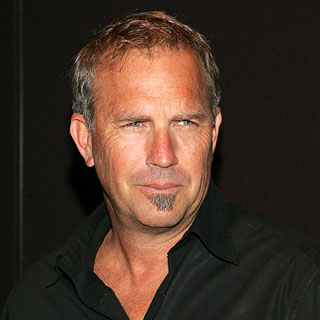

In his director's commentary on the DVD, George Cosmatos (above) takes full credit for the historically authentic details of the story and look of the film, even though he had nothing to do with these things. He also reveals the secrets of his approach to shooting the film, which involved using multiple cameras to record each scene, so the editor could make the choices he didn't know how to make on the set, and varying the style of the shots as much as possible, to create “interest”. This is the craft of a journeyman, at best. Cosmatos was a competent journeyman.

After Cosmatos died, Kurt Russell “revealed” that in fact he himself had directed the film after Kevin left, using Cosmatos as a front. He did it by stealth, giving the stooge Cosmatos shot-lists the night before each day's work and executing his ideas on the set by a series of hand signals he and Cosmatos had worked out. This would constitute the first time in film history that a movie has been secretly directed by someone without anyone else on the production suspecting the fact. The idea that you can direct a film with shot-lists and hand signals is beyond ludicrous — it's pathetic.

Russell and Cosmatos seem to have known so little about what directing a film actually entails, or I should say what directing a film well actually entails, that they may have believed their sad fantasies of themselves at the true auteurs of Tombstone. In any case, Cosmatos probably knew he could get away with retailing his fantasies on the DVD because Kevin was never much interested in re-fighting the battle of Tombstone in public. Russell certainly knew that he could get away with trashing Cosmatos's contribution to the film, such as it was, because Cosmatos could not argue back from the grave.

I knew Cosmatos slightly, and I know he was extremely proud of having directed Tombstone. It's not easy to replace a director while a shoot is in progress, and Cosmatos got the job done, however one might evaluate the quality of his work. I have a lot of respect for Russell as an actor, and he gave a fine performance in Tombstone — but even if he did secretly direct the very badly directed film, the fact remains that decimating Cosmatos's legacy the way he did, when Cosmatos was no longer around to defend it, strikes me as just this side of nauseating. Russell should have put his name on the film as its director or kept his mouth shut. If the film had tanked at the box office and had no reputation today, I strongly suspect that he would have kept the secret of his extraordinary accomplishment to himself.

People are used to merely throwing up their hands at dishonorable behavior like this because “it's just the way Hollywood works”. But it only works that way because enough people throw up their hands, and in many cases actually respect the yacks for possessing enough power to behave like insolent curs and get away with it.

In the interview in which Russell revealed his secret authorship of Tombstone, he said he respected Kevin Costner for trying to prevent the release of Tombstone, so it couldn't compete with Costner's (far inferior) version of the tale, Wyatt Earp. “He was playing hardball,” Russell said. No, he wasn't playing hardball. In hardball, as Earl Weaver once said, “you've got to put the ball over the plate and give the other fellow his chance”. Men play hardball. Collapsed males play the Hollywood game.

I think the rage I felt watching Tombstone again is useful — following the principle that “the tygers of wrath are wiser than the horses of instruction”. The moment has come when filmmakers, and the culture, need to say, as Wyatt Earp says in Kevin's script, when he's had enough of the insolence of the curs, “You tell 'em I'm coming . . . and hell's coming with me, you hear? Hell's coming with me!”

Anyone who has a problem with this can step right up and get their time. I'm your huckleberry.

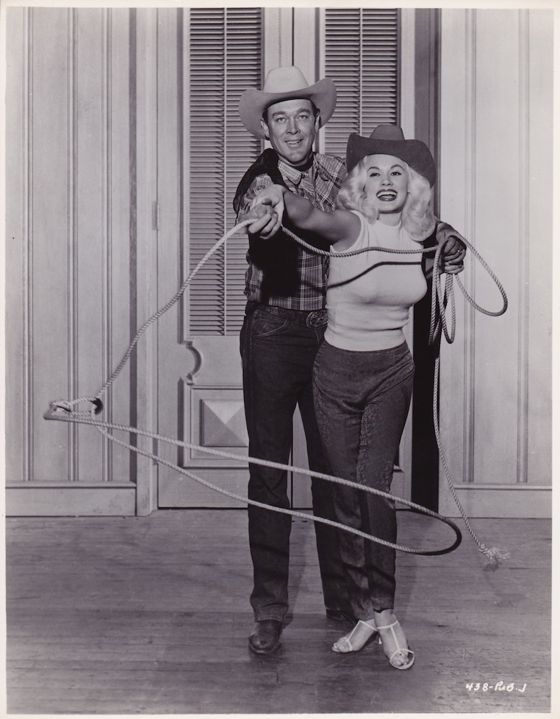

An amusing publicity shot of Ben Johnson and Mamie Van Doren, courtesy of Paula Vitaris, who hosts a great Ben Johnson fan site here. Paula thinks the photo probably dates from 1949, when both actors were working at RKO, and observes that Mamie seems to be having a grand old time while Ben is wishing he was somewhere else.

Paula recently posted a series of screen caps and a review of Cherry 2000 on her site, to which I contributed some memories of my brief encounter with Johnson on the film. You can find it here, under the date of 8 May.

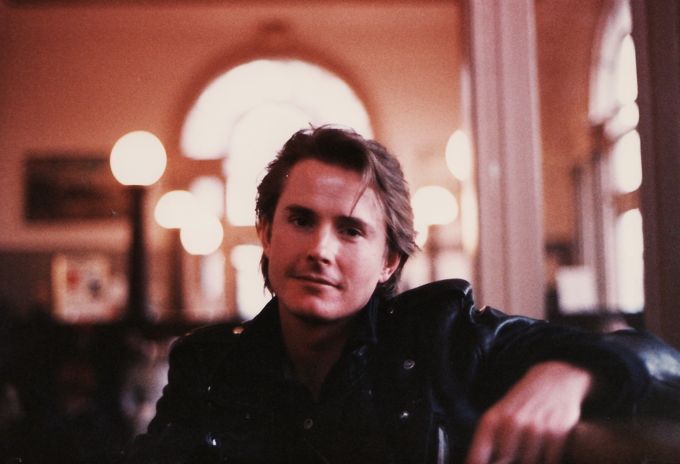

My friends Kevin and Darci after taking blue ribbons in separate events

at the Funkhana, an amateur rodeo competition at Tanque Verde Ranch in

Arizona. Kevin was an experienced horsebacker, Darci not so much, but

she willed herself into first place in a state of excitement which the

horse picked up on, somehow understanding that he and Darci could not lose. Watching the performance, Kevin said, “Look, Lloyd — two beautiful creatures being hysterical together.” An image from golden days long past.

My friend Kevin Jarre died earlier this month. He was four years

My friend Kevin Jarre died earlier this month. He was four years“Of course I know how to ride a horse,” I said.

“No, you don’t. You don’t know anything about riding a horse. But I’m going to teach you.”

He gave me one of the two McClellan saddles he owned, and one of the

two horses he kept out at a stable in Sylmar, at the northwest edge of

the San Fernando Valley, and we started riding together every day, just

after dawn, up in the San Gabriel Mountains above Sylmar.

Kevin taught me everything he knew about horses, which was just about

everything there is to know about horses. He taught me that the trick

of riding is trying to be as decent and noble and gallant as the animal

who’s carrying you — and to learn how to do it with ease and grace.

I tried to absorb what he taught with my mind, but what he taught were

things you can only learn with your body and your heart. Once, when I

was trying to learn how to sit the trot — not the easiest thing to do

in a McClellan — he said, “Lloyd, can you just forget for five seconds

that you were raised Protestant?”

Sometimes when I’m drifting off to sleep I’ll retrace one of our trails

through the San Gabriels in my mind, trying to remember every turn of

it.

Kevin is always with me on those ghosts rides, and always will be. He

was a fine horseman, and fine horsemen are in touch with something

eternal.

Cast a cold eye on life, on death.

Horseman, pass by!

[Warning — a few plot spoilers here.]

Movie Westerns are about the spectacle of the Old West, of course, about the history of the frontier and America's collective memory of it — but none of these these things quite sums up, much less defines, the genre. The genre has always been a vehicle for showcasing, reviewing, sometimes redirecting but always celebrating American values. It's not concerned with sociology — dispassionately analyzing the actual values Americans have lived by — but with moral aspiration, with stories that endorse the values we think we ought to live by . . . in a form that says, accurately or not, “We have always lived by these values, these values have made us what we are.”

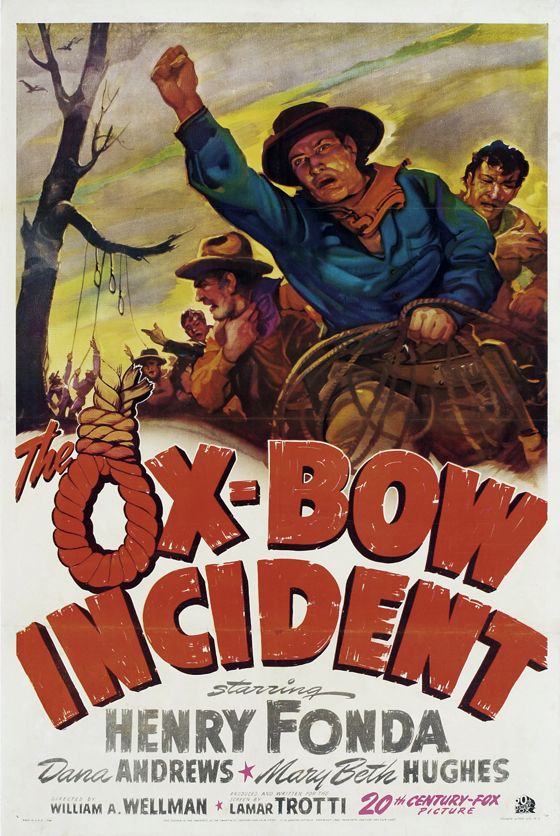

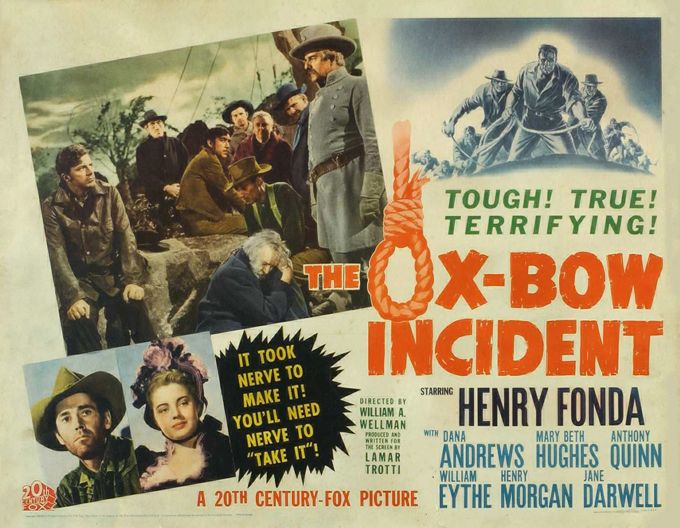

Westerns which don't do this may, like The Ox-Bow Incident, from 1943, look very much like regular Westerns, they may deal with the same themes and feature the same iconography, but they don't feel right. They don't feel like Westerns, and people who like Westerns won't go see them.

The Ox-Bow Incident is a very well-made film, with a compelling drama. But it's based on a novel which offered a kind of critique of the Old West and its values, a critique of frontier justice. Written in the late 1930s, it had a contemporary agenda — it wanted to warn Americans of the dangers of fascism, then rampaging through Europe, and to condemn lynching in other American contexts than the Old West.

It tells the tale of a successful lynching, and shows how decent men can become a party to such a thing. It shows cowboy hero types as complicit in socially sanctioned murder.

These are all valid things to do in the context of a period film, but when they're done in the context of a Western, they disorient audiences. Lynching is a common theme in Westerns, and almost always condemned, but condemned through the medium of the lone hero who stands up to the angry mob and stops it. It may be more powerful, and in some ways more honest and realistic, to make us identify with the hero who can't stop it — to implicate us in his failure. But this is not how Westerns typically work.

Audiences of 1943 stayed away from The Ox-Bow Incident in droves, despite glowing reviews and several Academy Award nominations, including one for best picture, and despite Henry Fonda in the starring role, giving one of his best performances.

The post-WWII, noir-inflected Western showed that authentic Westerns could get very dark indeed and still redeem even a neurotic hero who managed somehow to rise to the occasion at the end and behave nobly. Audiences had no problem embracing these more nuanced and complex and troubling variants of the formula. But with the rise of the anti-Western in the 1960s — Westerns which denied the reality, the validity of traditional American values, which grew cynical about the code of the hero — audiences reacted just as they had reacted to The Ox-Bow Incident in 1943. After an initial bout of enthusiasm, fueled by the novelty of the thing, the frisson of transgression, they stayed away in droves.

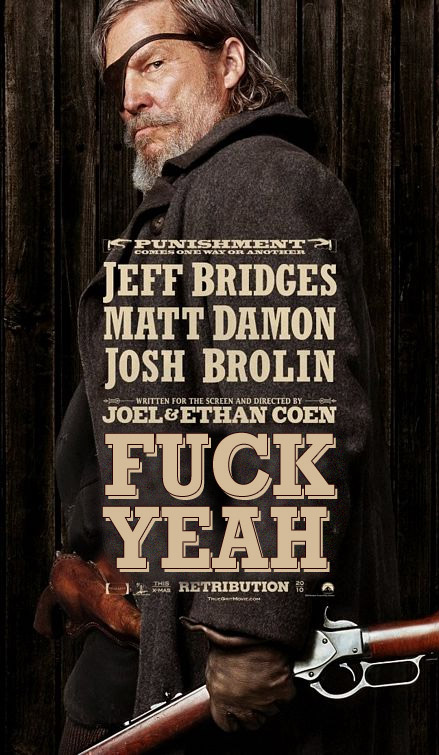

They're always ready to come back, however, when an authentic Western appears on the horizon — as the Coen brothers' True Grit recently proved. It's not a hard phenomenon to understand — except, apparently, in Hollywood. The extraordinary commercial success of the new True Grit — now closing in on a quarter billion dollars in international grosses — will undoubtedly lure someone else in Hollywood to try another Western. It will, most likely, be a Western that cynically challenges traditional American values — because that's the hip thing to do. When it flops at the box office, Hollywood will say, “Well, we were right all along. People don't like Westerns. True Grit was a fluke.”

But the success of True Grit wasn't a fluke, anymore than the failure of The Ox-Bow Incident was a fluke. It's all about what Westerns are, what people want them to be — need them to be.

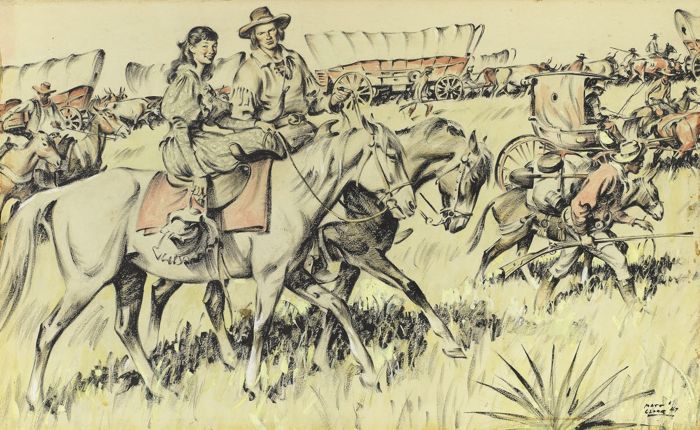

“Bonanza, The Comstock: A Caravan Returns to Gold Canyon”, American Weekly story illustration, 1947.

The Comstock Lode was the first major deposit of silver located in the United States, in 1858, in what is now Nevada but was then the western part of the Utah Territory. It created a rush similar to the California Gold Rush, leading to the founding of Virginia City — a place of fabulous wealth and vice — and the creation of the state of Nevada. The lode was pretty much played out by 1874. Virginia City has only about 1,500 residents today and makes its money mostly off of tourism, because many remnants of its former splendor are still standing, out in what is now the middle of nowhere.

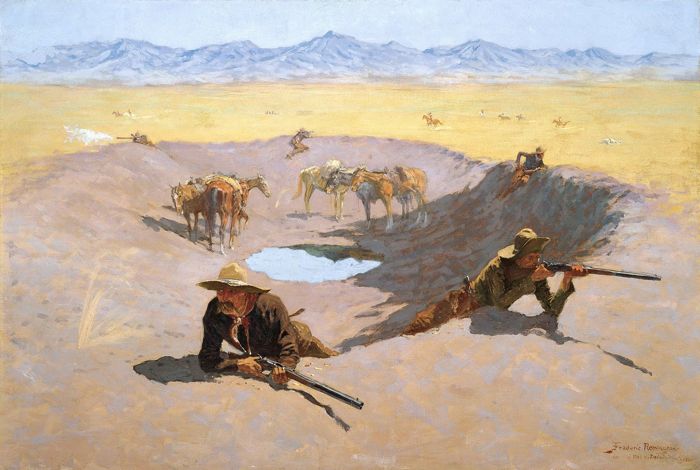

The Fight For the Water Hole — a narrative image that became a staple in Western movies. The painting dates from 1903, the year of the wildly popular short film The Great Train Robbery, a Western, which helped establish the story film as the dominant genre of cinema. This was the era when the mythic iconography of the Old West was becoming codified. Coincidentally or not, the coda of the Coen brothers' True Grit is set in 1903.

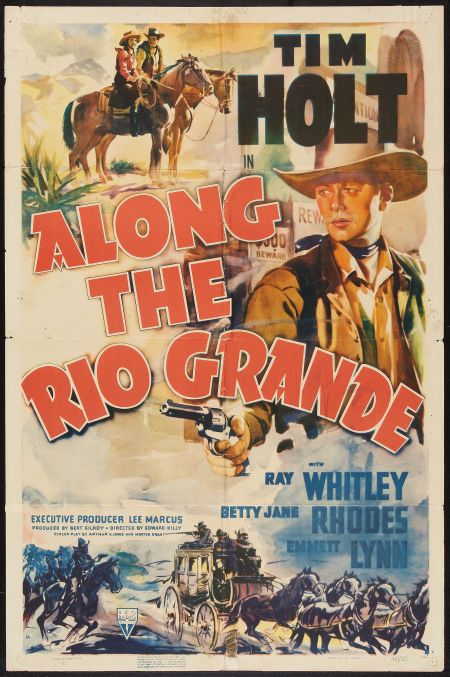

Most B-movie Westerns were done as parts of series featuring a star and

recurring actors in supporting roles, often a comic sidekick but

sometimes a musical sidekick, if the star wasn’t himself a singing

cowboy. The bad guys and the female romantic leads changed from

picture to picture.

When RKO set Tim Holt up as the star of his own B-Western series in the

early 1940s, they gave him a comic sidekick and a musical sidekick.

Even when a B-Western star didn’t have a musical sidekick, musical

numbers were usually a part of the formula in the 1930s and 1940s, and

they were usually anachronistic — Western Swing numbers written for

the films rather than authentic cowboy songs.

Along the Rio Grande, from 1940, is the first film in the new Tim Holt B-Western

collection from The Warner Archive which features Holt in the starring role. It was, I believe, the third B-Western in which he starred. (He had earned his spurs before this playing second leads to more established B-Western stars.)

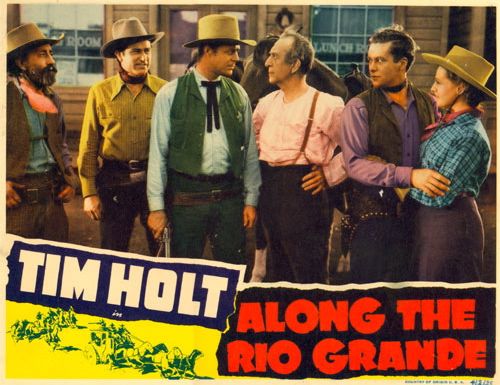

These early Holt Westerns play like variety shows rather than dramas.

Dramatic exposition and action sequences alternate with musical numbers

and comedy bits in a regular pattern. In a way they harken back to the

Western arena shows of the 19th Century, which were essentially variety

shows with a Western theme, mixing staged dramatic spectacles — mini-narratives, like the attack on the stagecoach, on the settler’s cabin — with self-contained acts featuring theatrical displays of marksmanship and horsemanship, all knitted together with musical

interludes.

A little something for everybody was the idea in most B-Westerns, too — all of a simple and unsophisticated nature, reflecting the primary audience for these films, kids

everywhere and older folks in the smaller towns and rural areas.

The variety is what keeps the films enjoyable even today. The

conventional plots and merely serviceable acting couldn’t sustain them

as works of drama, but (as was true in vaudeville, or Buffalo Bill’s

Wild West) you always knew there was going to be a change of pace soon

— another routine by the comic sidekick, another song, another awkward

but charming interchange with the leading lady, another thrilling chase

on horseback.

There’s usually a lot of entertainment packed into these short films —

modest, perhaps, but pleasantly varied. The horsemanship is always

first-rate, though, and if all else disappoints, you rarely have long

to wait before someone says, “We’ve got to head them off at the pass!”

. . . at which point the screen will explode with beautiful images of

beautiful animals galloping through scenic landscapes, with heroic

figures in the saddle, bent on righting one wrong or another. If for

nothing else than this, the B-Western remains a delightfully dependable

form of amusement.