Of the many pleasures B-Westerns can deliver, not the least of them is incoherence — both narrative incoherence and conceptual incoherence. These movies were made quickly, to fill out release schedules. “Elements” — stars, character types, action sequences, themes, locations — were taken from an existing pool and sometimes thrown together illogically, just to get something in the can and out to theaters in time for next Saturday's matinee.

The results can be oddly exhilarating.

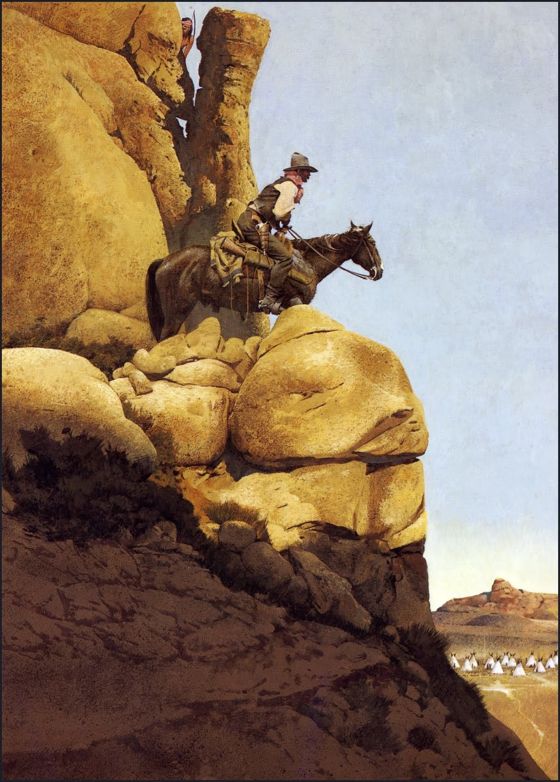

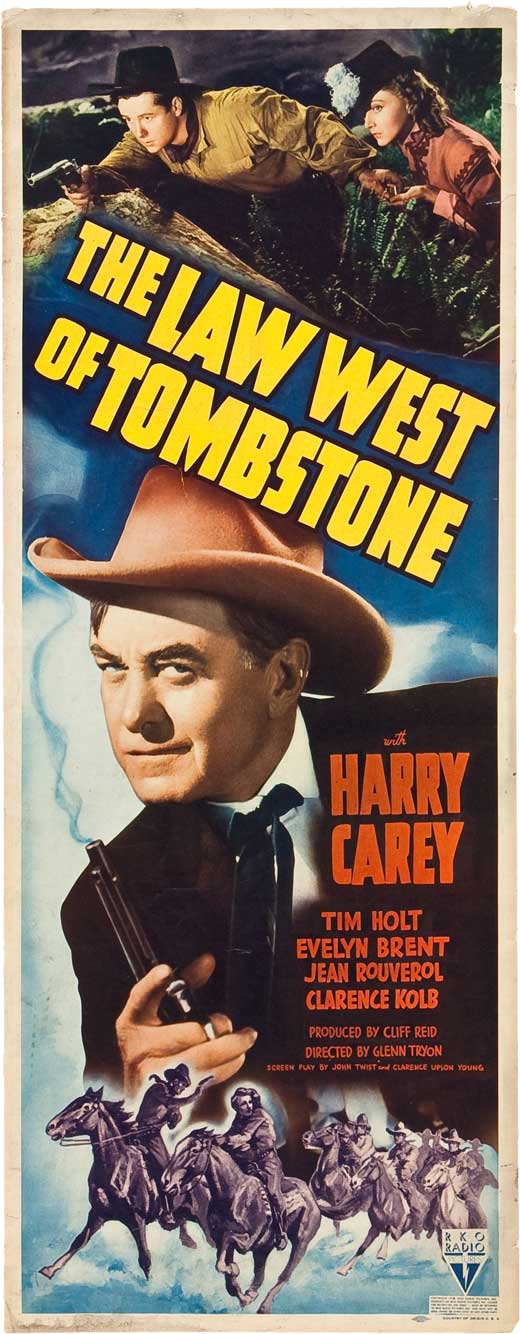

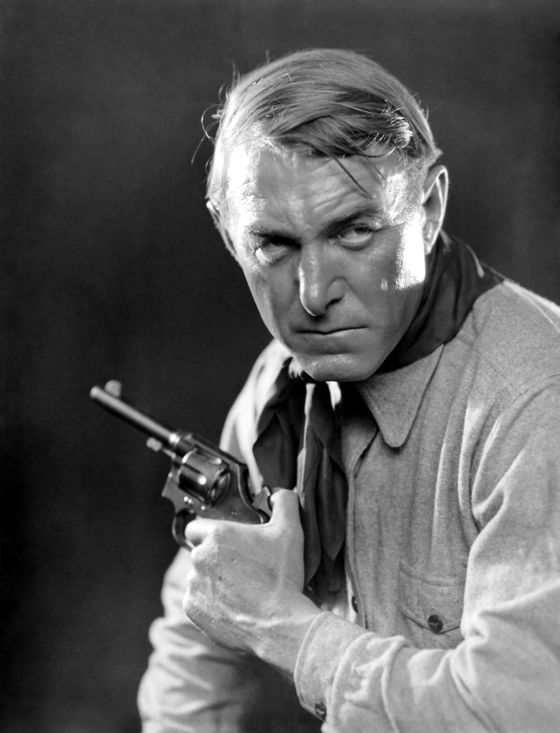

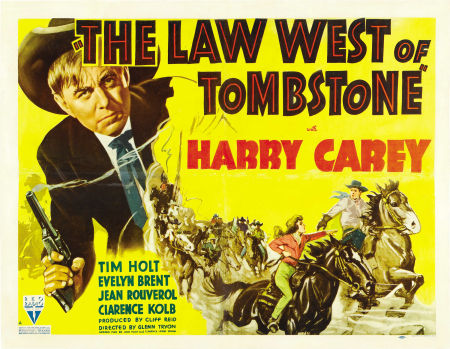

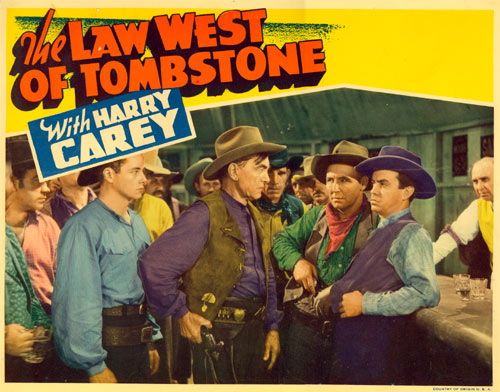

A case in point is the second film in the recently released Tim Holt collection from The Warner Archive, The Law West Of Tombstone. Holt plays the second lead here in a film starring Harry Carey (above). Carey was a big Western star in the silent era, most famous for his collaborations with John Ford, and he still had enough of a following to allow him to carry a B-Western well into the 1930s, but he was getting too old to play a traditional leading man by the time this film was made, in 1938.

The solution was to make Carey a kind of featured character actor, and to let the much younger and more vital Holt handle the romance and the big action sequences. It was all part of a process — Carey's name and his reputation as an authentic Western star sold the picture to aging fans of the genre, even as Holt was being groomed as a Western star in his own right, someone who could appeal to the younger fans.

The sequences featuring Carey and the sequences featuring Holt have not been fully integrated with each other. You get a sense that they were conceived separately and then cobbled together without regard for dramatic consistency. Carey is introduced in New York, running an improbable scam on a wealthy Easterner, then shuttled back to the West where he's soon sentenced for another scam, and given a reprieve in return for bringing the “Tonto Kid” to justice.

Holt plays the Tonto Kid, and the Carey character has no intention of bringing him to justice — he actually wants him to marry his daughter, who doesn't know she's his daughter. The daughter is engaged to marry the Tonto Kid's partner in crime, who's a genuine bad guy. The Tonto Kid kills him in self defense in a bar fight, but the daughter thinks it's a case of murder. “You killed him!” she screams at Holt. “Yeah,” Holt says, with a casual “so what?” look on his face.

At this point, the plot transforms itself into the tale of a range war between some local ranchers and a tribe of Indians being manipulated by corrupt agents. Did I mention that the Carey character has a pet monkey?

It's all quite mad.

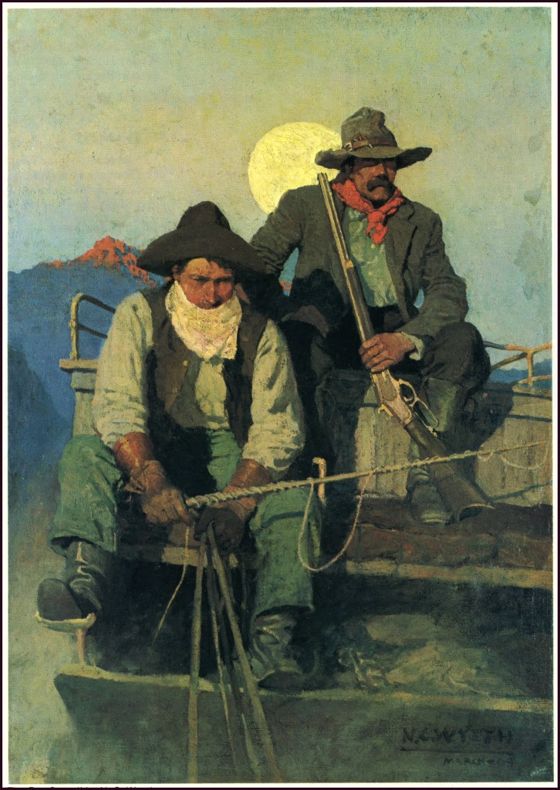

In the midst of the muddled melodrama, there's a train robbery, preceded and ended by stunning shots of the robbers, Holt and his partner, boarding and escaping from the train — off of and onto the backs of horses running beside the train. These are shot from the platform at the back of the train in single takes, without stunt doubles. The images are incredibly exciting and beautiful, and when you're watching them you just don't give a damn about the plot anymore. On some level they justify the whole film.

Fans of Josef von Sternberg's silent films will be tickled to see Evelyn Brent, who starred in two of them, featured in The Law West Of Tombstone in a

supporting role as an aging gold-digger, who's an old flame of the Carey character — another nod, perhaps, to the audience's nostalgia for the silent era. There are echoes within echoes in the Western genre here. In von Sternberg's film Underworld, Brent plays a character called “Feathers” (above), the nickname given to the Angie Dickinson character in Rio Bravo in homage to the earlier film, from which Hawks also borrowed the spittoon gag in the opening scene with Dean Martin. And in the last shot of The Searchers, John Wayne delivers one of Carey's signature gestures, grabbing on to his left arm with his right hand, as an homage to the late Western star. Carey's son Harry Carey, Jr. appears in many Westerns by Ford and other directors, including Hawks, and Carey's widow Olive Borden appears in The Searchers.

If The Law West Of Tombstone had been made last year, we might be tempted to read it as a deconstruction of the B-Western form, and to find the exercise extremely witty and sophisticated, charmingly surreal. Audiences of the time may have experienced it in much the same way, as an incoherent but delightfully demented compilation of familiar elements — a kind of freewheeling jumble with its own bizarre integrity, like a pile of pieces from a disassembled jigsaw puzzle. You enjoy each element for what it is, and your enjoyment becomes the film's organizing principle, in the absence of any other.