My nephew Harry and I, a couple of movie-mad kids at heart, made a pilgrimage last week to Lone Pine, California, to pay our respects to a location where scores of Westerns and other kinds of films have been shot over the years.

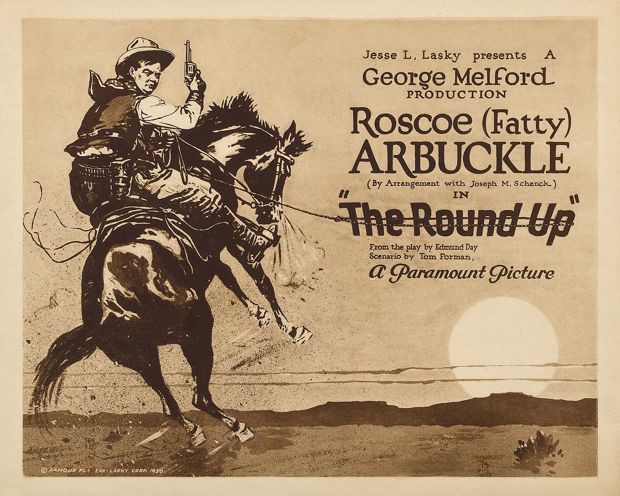

Fatty Arbuckle made The Round-Up there in the silent era (1920), and most of the exteriors of Gunga Din were shot there, incorporating some massive sets constructed in the Alabama Hills, in 1938.

Many of the films in the Hopalong Cassidy series were made in and around Lone Pine . . .

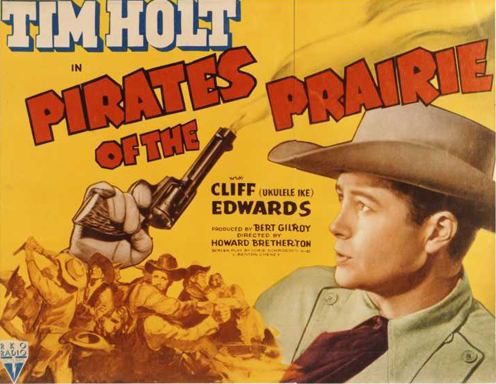

. . . and many of the Tim Holt Westerns, too.

The films in both of those series are beautifully shot — they are B-Westerns with first-class cinematography and can be watched over and over again for the aesthetic pleasures of their images alone.

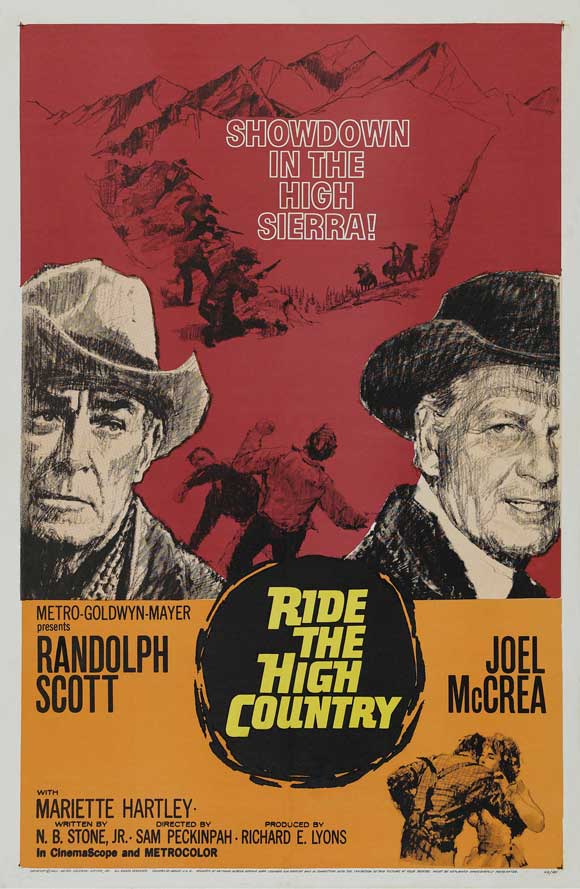

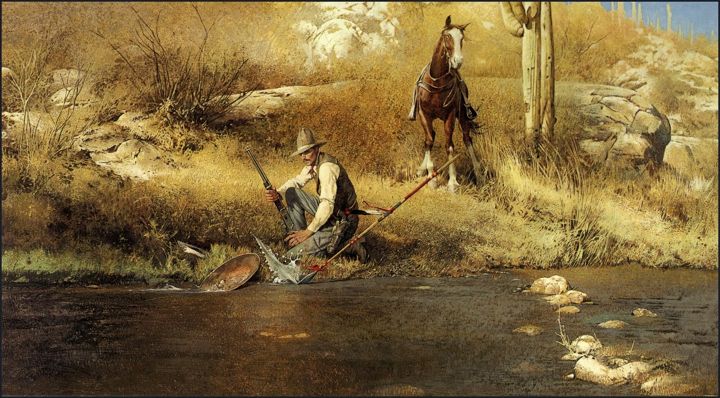

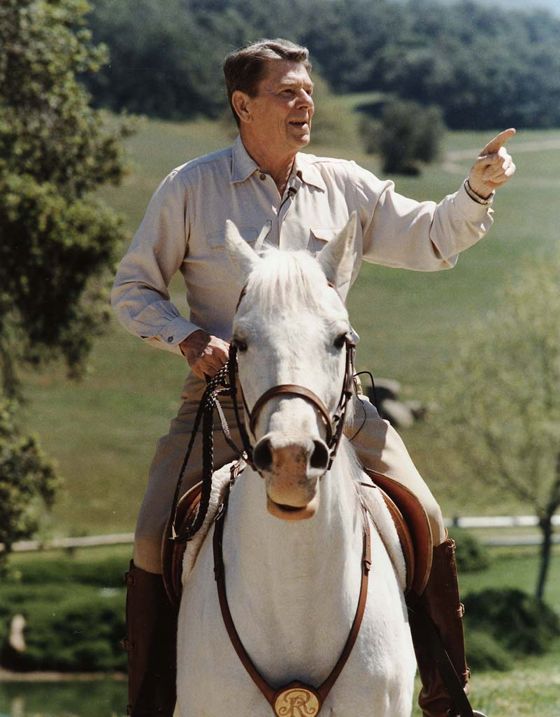

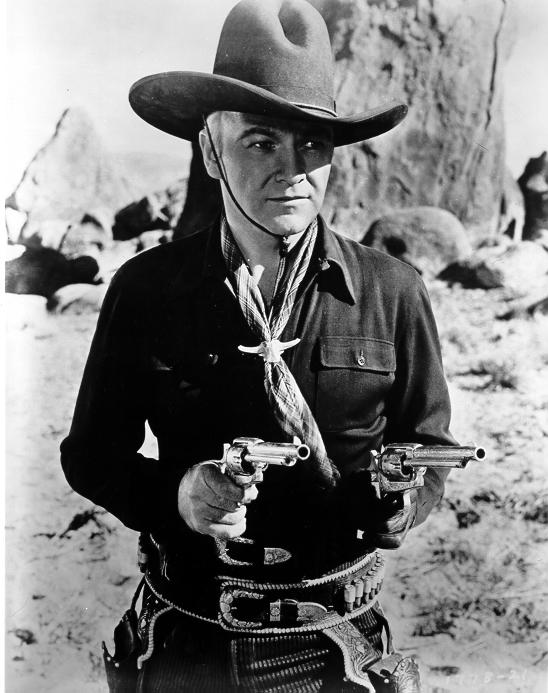

The greatest films shot in and around Lone Pine were the Randolph Scott-Budd Boetticher Westerns, including The Tall T (above), Ride Lonesome and Comanche Station (below), and these films have consecrated the locale for me. Lone Pine and the nearby Alabama Hills were for Boetticher what Monument Valley and Moab, Utah, were for John Ford. I wanted to move through that landscape and see the raw material from which Boetticher conjured his enchanted spaces.

I was also doing a very preliminary location scout for a no-budget Western I'm working on, wondering if Lone Pine might be a place it could be made.

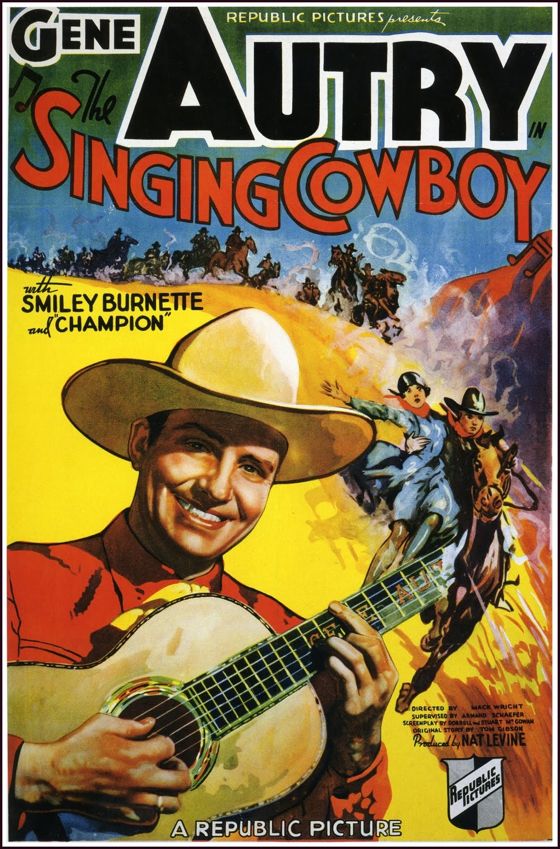

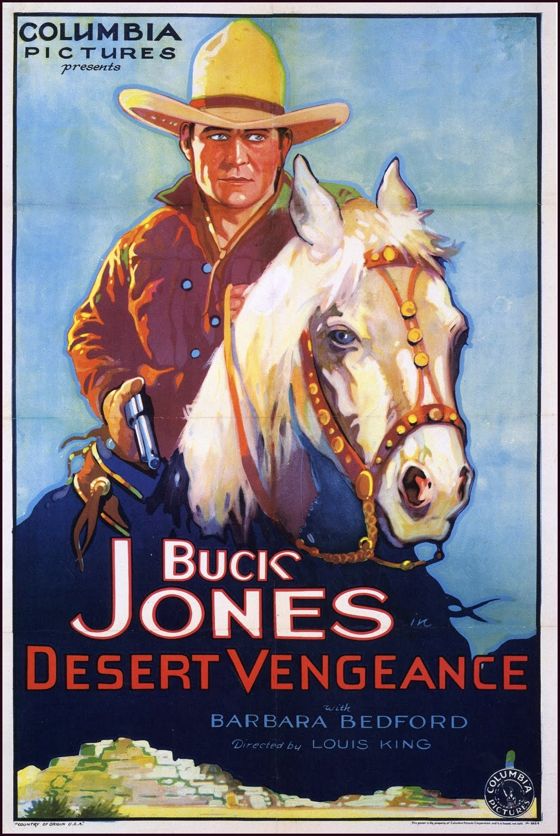

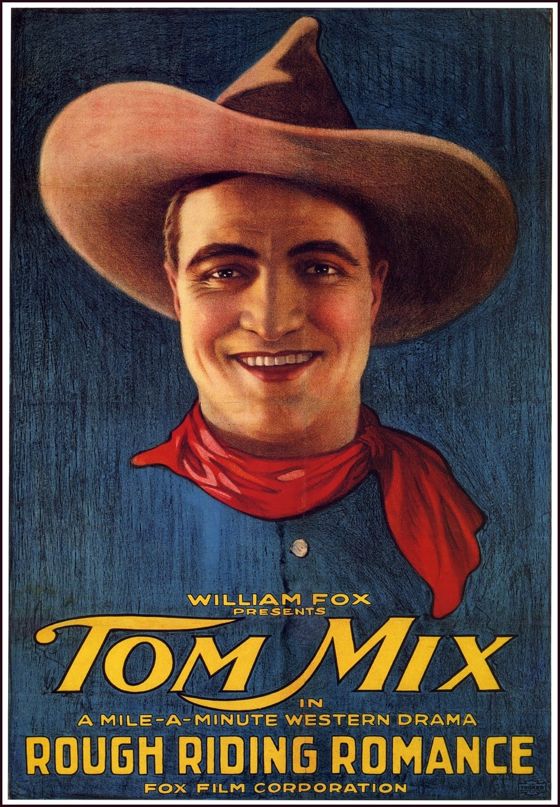

We started out our day at the excellent film museum in Lone Pine, which has an amazing collection of posters from the films shot in the area and a number of sublime artifacts — the most sublime of which was a cowboy hat worn by Barbara Stanwyck in a film made at Lone Pine. My heart skipped a little beat as I stood before it, thinking of the way that woman could sit a horse.

The lane above runs next to the museum.

Like Monument Valley and the valley near Moab through which the Colorado River flows, Lone Pine has a lot of different-looking landscapes concentrated in a small area — which facilitates rapid company moves on a low-budget shoot. You can get a sense of numerous contrasting locations with minimal logistical complications.

The Alabama Hills are a labyrinth of odd rock formations, passes and basins. Minutes away to the east the Owens River runs through shady groves and reeds — familiar from the beautiful river crossing scenes in the Boetticher films.

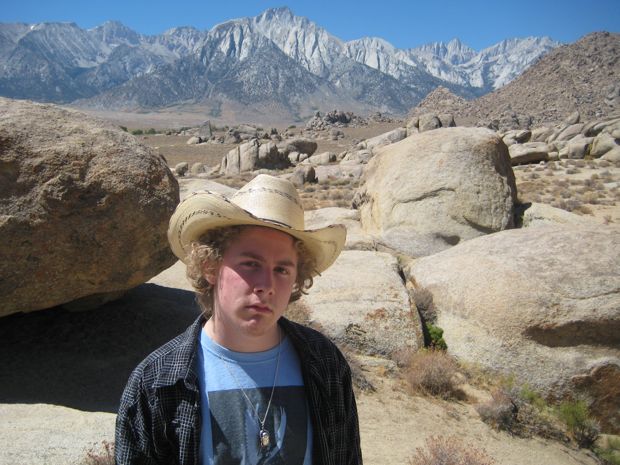

One of the glories of Lone Pine is the range of the Sierra Nevadas looming up to the west of the Alabama Hills.

It makes for some spectacular scenery, but would be a problem for my film, which is set in North Texas, where such mountains do not exist. Working in the Alabama Hills or along the banks of the Owens, which could stand in quite well for Texas, one would be severely limited in the directions from which one could cover a scene, but it's probably a limitation one could live with.

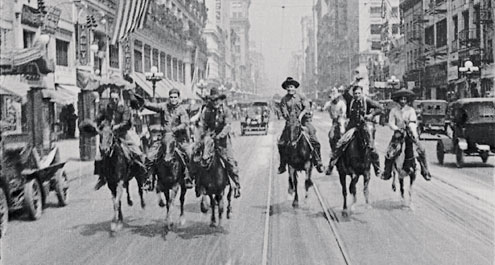

But that's a problem for another day. The day we spent in and around Lone Pine was magical — it's ground haunted by galloping ghost horses ridden by ghost cowboys, whose images live on, even in these degraded and ignoble times.

We drove back through the furnace of Death Valley that afternoon . . .

. . . and sped straight to the In-N-Out Burger for sustenance. That night, inspired by the grand Western landscapes of Lone Pine, Harry watched Jean Renoir's La Règle du Jeu for the first time.