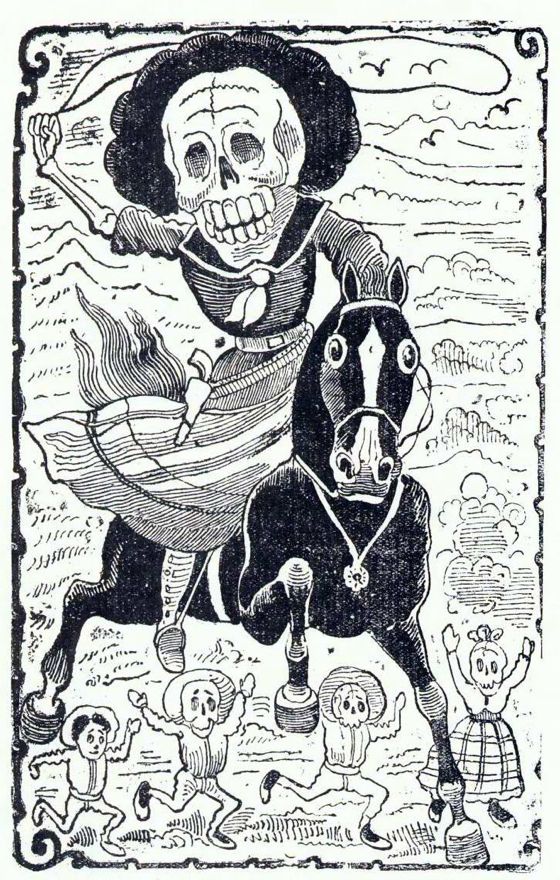

A calavera by José Guadalupe Posada.

A calavera by José Guadalupe Posada.

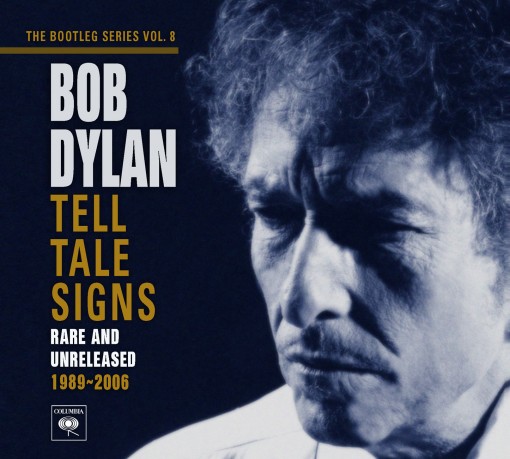

Bob Dylan’s song “Red River Shore”, from the compilation album Tell Tale Signs, has no direct precedents that I know of, but it references a couple of older cowboy songs. The first is “Red River Valley”, a standard from the second half of the 19th Century:

From this valley they say you are going.

We will miss your bright eyes and sweet smile,

For they say you are taking the sunshine

That has brightened our pathway a while.

So come sit by my side if you love me.

Do not hasten to bid me adieu.

Just remember the Red River Valley,

And the one that has loved you so true.

The last line is often rendered as “And the cowboy that loved you so true”.

This song in turn was probably influenced by (or possibly influenced) another cowboy song, based on an old English ballad, “The Girl From the Red River Shore”, whose title is a recurring phrase in Dylan’s song.

Both are songs about loss — the second describes a cowboy who gets into a fight while riding to marry a girl from the Red River shore. Her father, who disapproves of the marriage, has ridden out to meet him with a cohort of gunmen — the cowboy kills several of them and now can never go back to claim his love.

I don’t know how old this second song is — an arrangement of it was copyrighted and recorded by the Kingston Trio in the Sixties but its words have a 19th-Century feel. I also don’t know why the Red River became associated with lost love . . . it was probably just an accident, although “Red River” does suggest the coursing of the blood, the beating of the heart.

Dylan’s song was recorded during the sessions for Time Out Of Mind but left off that album for some reason. Curiously, it influenced a song on a later album, Modern Times, “Nettie Moore”. The title and the first two lines of the chorus of that song were taken from an 1857 song called “Gentle Nettie Moore”, which is about a man’s longing for a young girl who has gone off somewhere else. The older song references good times past, including boating on a river, and Dylan adds a river to the chorus of his song, after the quoted lines:

Oh, I miss you Nettie Moore

And my happiness is o’er

Winter’s gone, the river’s on the rise

I loved you then and ever shall

But there’s no one left here to tell

The world has gone black before my eyes

This echoes the plight of the narrator of Dylan’s “Red River Shore”, who goes back to the place where he knew his lost love and can’t find anyone who remembers her, or them together. In a final, mystical image, the narrator wonders if anybody anywhere ever saw him, except that girl — suggesting that he only had authentic being in her eyes, that if she isn’t looking at him he’s dead. This is why that last verse references Rabbi Jeshua of Nazareth, someone who knew how to bring the dead back to life. If the girl from the Red River shore is really gone, then the rabbi might be the only hope of life left, a dubious hope in the narrator’s estimation.

The song thus becomes something much more than an exercise in nostalgia, in romantic longing — it becomes a kind of cry of existential terror.

One day, as you drift into your fifties, you wake up and realize that you are closer to the end of things than to the beginning. It’s not necessarily a bad or depressing realization, but it does induce different kinds of thoughts than you’ve ever had before. It makes you think seriously about what your life might add up to, when all is said and done. Lost loves come back to haunt you. For me these ghosts are often sweet revenants, because they remind me of the times I did feel most alive, of the times when my being seemed fullest.

In “Red River Shore”, Dylan has written a great song about this phenomenon. It will certainly speak most clearly to people who are nearer to the end of things than to the beginning — but the truth is that this could be any of us, for all we know, whatever age we’re at, and all of us will get there eventually.

There’s a girl (or guy) from the Red River shore in every life, and eventually he or she will become a ghost, even if it’s only the ghost of the youth of someone you’ve always been with. Eventually that ghost will show up at your door one day and say, “Remember me?” . . . and the question will really be, “Do you remember who you were when you were most alive?” It’s an important question — since that memory might be the only thing you’ll take with you from this world, the only thing worth taking with you from this world.

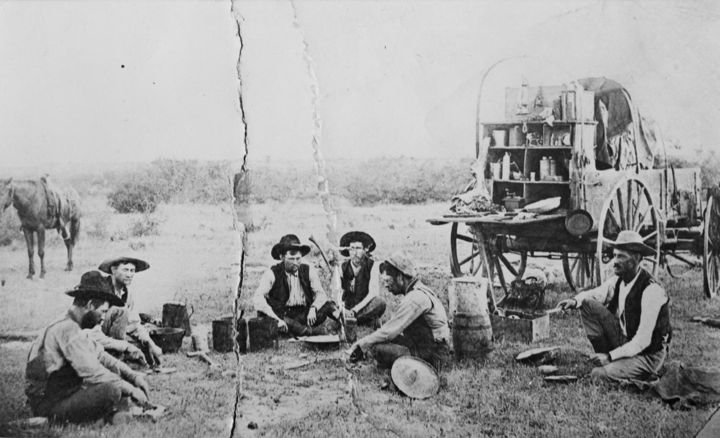

. . . on the Texas plains in the 1880s.

The girls of Little River they're sweet and they're pretty

The Sabine and the Saber have many a beauty

The banks of Nacogdoches have girls by the score

But down by the Brazos I'll wander no more

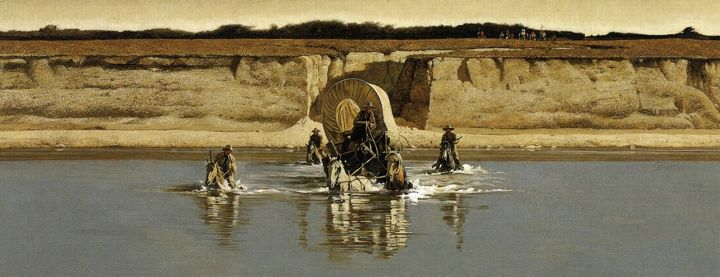

Another wonderful Western painting by Robert McGinnis. Horses and wagons crossing rivers are seminal images in movie Westerns — for Ford and Boetticher they had a spiritual quality. They would create little poems out of them, little arias, stopping the narrative to show the process in detail.

Here's Don Edwards singing the cowboy song quoted above — a Homeric catalogue of Western river names, laced with rue over a lost love:

Down By the Brazos

[Right grateful to Golden Age Comic Book Stories for the image.]

Red River Valley

The composition is a bit static, though I guess you could also call it monumental, iconic. Pretty cool, all the same.

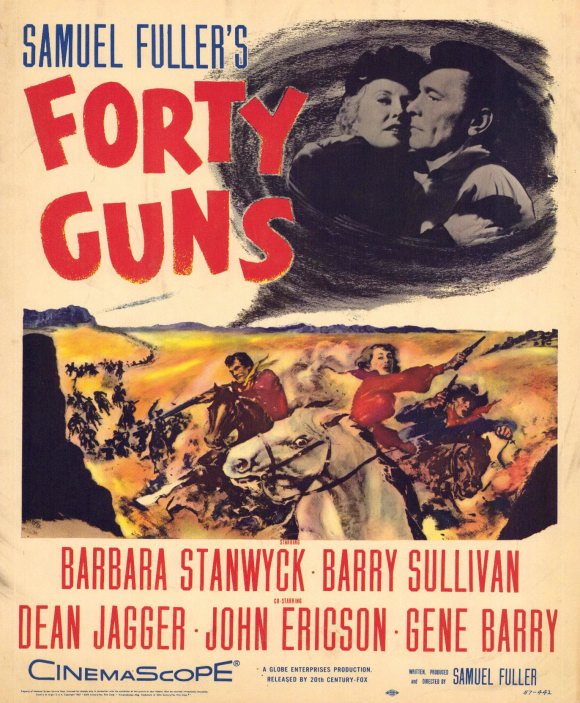

If you haven't seen it, there's no way I can convey to you how strange this 1957 Samuel Fuller Western is. I can tell you it's about a mythically powerful woman who rides the territory of her ranch with forty hired guns, like an escort of armed valets. She is a primal variant of the femme fatale, wreaking havoc on a world of collapsed males. Her type is not unknown in films of the Fifties, especially in film noir, but here she takes on the dimensions of a Greek goddess, terrible and timeless.

Her power is contested, and ultimately overcome, by a man willing to stand up to her, reducing her to a state of pliant femininity — which rarely happens in film noir — but at the same time she's such a vivid embodiment of the nightmare of the collapsed male that the triumph of the hero here feels provisional. She might have been vanquished in last night's dream, but she'll be back in tomorrow night's dream — you can count on it. The threat she poses is eternal. (Fuller had a darker fate in mind for his fatal femme but the studio vetoed the idea.)

What I can't convey is the American-Gothic vision of the Old West Fuller has concocted — it's as though Poe has lit out for the territory and found the same sickly-sweet decay in the Western myth that he found in the European myths back east.

Fuller deconstructs the classic beauty of the best-looking Western films, of Ford and Wyler and Hawks, by pushing their methods into realms of extreme self-consciousness. His camera travels endlessly on tracks, swoops deliriously on cranes, exaggerating the conventions into a new form, one with no restraints on style.

This is a Rococo Western, in which style breaks loose from narrative goals and serves only archetype.

It's a very odd and very beautiful film, and not like any other I know. By the time directors like Godard began to embrace Fuller's daring methods of self-conscious filmmaking, they were ready to abandon genre itself, except as an ironic referent. (It's worth noting, however, that Godard quoted a shot from Forty Guns in Breathless — it was clearly on his mind as he began to forge his own style.)

Fuller stays inside the Western genre in Forty Guns but lays waste to it mercilessly from within. Only a man who loved the form could have done this, just as only a man who loved women could have feared them as much as Fuller fears the commander of the forty guns, the high ridin' woman with the whip.

From 1920, when Westerns were Westerns and movie posters were works of art.

[From (where else?) the wondrous Golden Age Comic Book Stories.]

I love the way she sits a horse — looking to sign on as her forty-first gun.

Budd Boetticher's Comanche Station might just be the greatest film ever shot in twelve days. It's lean and mean, with a small cast, absolutely no interiors and only two exterior sets that needed dressing. Its script is short, with terse dialogue that suggests much without going into detail about anything.

As a model for how to shoot landscapes, with people and horses moving through them, the film cannot be bettered, even in John Ford's Western oeuvre. Some of the long tracking shots of people riding and talking are like self-contained lyric poems. The action sequences are choreographed with unerring skill, a sure sense of the drama inherent in complex movements through space — beautiful without ever becoming glamorous.

Horses are not props in this film, as they are in almost all modern Westerns — they are true characters in the story, shot with admiration and respect for their magnificence and grace and power. Boetticher knows that a horse and rider crossing a deep river is among the most beautiful things it's possible to witness on this earth.

One could almost call this a chamber Western, except that there are no chambers in it — only rugged country and big skies and people trying to stand out against them. In Boetticher's universe, they do this by acts of moral, not physical, heroism, although the latter tend to flow inevitably from the former. It's a small work by Hollywood standards, but it's bigger than Avatar in its mastery of storytelling and cinematic form — it gets its 3D effects the old-fashioned photo-chemical way. It dazzles, blows you away, by its simple, elegant perfection.

Rio Grande, from 1950, the last film in John Ford’s cavalry trilogy, isn’t really about the cavalry, it’s about marriage, and like any serious work about marriage it deals with the subject of boundaries — boundaries respected, boundaries transgressed and boundaries transcended.

“Love is the mutual respect of two solitudes,” says Rilke, but in a marriage those two solitudes interpenetrate, in the partnership of daily living, in sexual intercourse and in the not unrelated phenomenon of bringing children into the world. To say that it gets complicated is to put it very mildly indeed.

The river that gives this film its title is itself a boundary, of course, between two countries. Its very name embodies its divisive nature — on the Mexican side, the river is called the Rio Bravo, reminding us that people don’t always have the same names for the things that separate them, complicating communication considerably. The river is problematic for the film’s protagonist, Colonel Kirby Yorke, played by John Wayne, because Apaches living on the Mexican side are raiding into U. S. territory and he can’t follow them back to their refuge below the border.

He is compelled to respect the boundary and also to find a way out of the dilemma this places him in. He offers to put his command under the authority of the Mexican army for the purposes of a punitive expedition against the Apaches, who are bedeviling Mexicans as well, but national pride prevents the Mexican army from accepting help.

This is a fine set-up for a Western adventure film, but it’s only a metaphor for the film’s real drama, which concerns Colonel Yorke’s marriage.

Yorke has been estranged from his wife for seventeen years, ever since, under orders, he burned down her family’s Virginia plantation during the Civil War, after which she came to hate soldiers, the profession of soldiering, and him. She took their infant son with her when she left him, but the son has become a soldier himself now, seventeen years later, against her will, and has been assigned to serve under his father at the remote fort near the Rio Grande.

Kathleen Yorke, played by Maureen O’Hara, shows up at the fort to purchase her son’s release from the army — but neither the son nor the father is prepared to sign the necessary papers, as they stare each other down across another kind of chasm, the awful chasm that exists between a father and son who don’t know each other.

Here, then, is one spectacularly dysfunctional family. Proximity saves them — proximity and the ritual etiquette of military life, of gallantry between the sexes. With personal passions roiling beneath the surface, they treat each other with respect, obeying the outward forms of civility, long enough to get to the bottom of things, to transcend their personal passions — bitterness, suspicion, resentment, shame, wounded pride.

The outward forms of civility, military and courtly, are all about respecting boundaries — establishing a border between people across which they have a chance of seeing each other as individuals.

But these borders exist to be crossed — and this is the ultimate profound and paradoxical message of Ford’s film. Yorke’s commanding general finally orders him to cross the Rio Grande in pursuit of the Apaches, in violation of international law. Yorke finally hauls off and kisses his wife, transgressing the line she has drawn between them. His wife offers to clean and repair his uniform — his soldier’s uniform, the symbol of everything she despises about him. The son crosses his own boundary into self-sufficient manhood, and the parents allow him to do it — and their re-established love for each other gives them the courage to do it.

People who see this film as simplistic, as an old-fashioned celebration of gallantry towards women, of military life, completely miss the point. The darkness in Yorke’s soul, the existential loneliness of his wife and son, are as devastating as any portraits of despair in a film noir. The rituals that save them are also the rituals that imprison them. There is no simple way to cross the Rio Grande — the cost of the crossing is enormous, almost more than the characters can bear. But the only salvation lies on the other side of the river.

Rio Grande is a film often damned with faint praise, but it’s one of the greatest of all American films, and in its deceptively simple, elegiac way, one of the deepest and wisest films ever made about marriage.

It’s a film whose sublime artistry is disguised by hiding in plain sight. Take for example the remarkable sequence in which Ben Johnson and Harry Carey, Jr. put on a display of Roman riding — galloping around a ring and taking a jump while standing on the backs of two horses running together. It’s a display enacted mostly for the Yorkes’ son Jeff, who must then try it himself, with mixed results.

Jeff has to learn a similar skill in life — finding a footing in the world of his mother and the world of his father, before he can come into his own as a man. And they must relearn how to work as a team in order to give him a chance to find that footing. The whole interior psychology of the film is thus summed up in a series of stunning visual images that on the surface read as a throwaway action interlude.

Cinema just doesn’t get any better or more eloquent than this.

[With special thanks to Dr. Macro’s High Quality Movie Scans for the illustrations.]

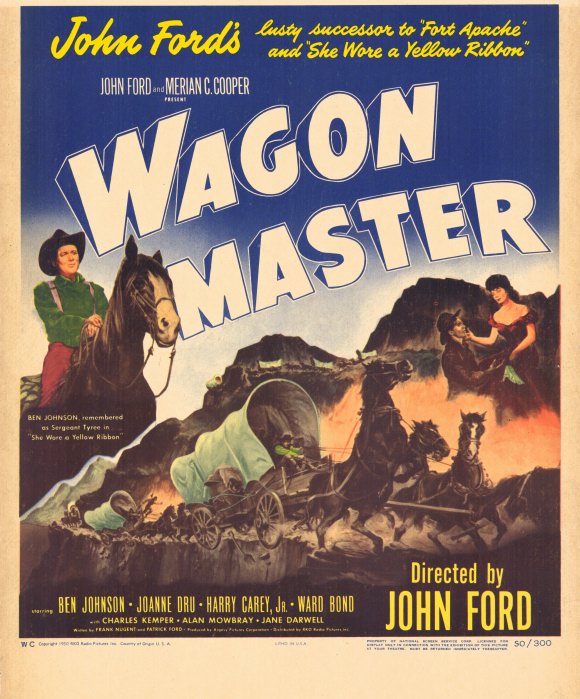

A few days ago I was driving with my friends Mary and Paul Zahl from Kayenta, Arizona, to Moab, Utah. We were going up to Moab to track down the locations where John Ford shot parts of Wagon Master (and other films.)

On the way, Paul suggested we make a detour to see the fabled Valley Of the Gods, a large basin surrounded by mesas and dotted with odd rock towers. My instinct was to proceed directly to Moab, but Paul's instinct was stronger so we set off on a dirt road into the valley.

It was a good road, of red clay — or would have been a good road if it hadn't been raining recently. The rain had turned it into glass. My big Navigator, in four-wheel-drive, kept losing traction on it, threatening to slide over the embankments on sharp turns. It was a little scary, but the car handled it all very well.

Then, at the end of the road, we found ourselves driving straight towards the nearly sheer face of a tall mesa. There was, improbably, a road leading up the side of the mesa in a series of hair-raising switchbacks. The maps we had said the road was paved, and it was, but only in parts. The other parts were wet dirt — something we discovered too late.

I started up the road, which is called the Moki Dugway — seen above in better weather conditions than we faced — and we all soon realized that we had made a big mistake. But I also realized that trying to turn the car around on such a road would probably be more dangerous than proceeding up it.

So we proceeded up it, at a snail's pace, with our hearts in our throats. I hugged the side of the mesa on the sharp curves, honking and hoping we wouldn't meet any oncoming traffic. There were no shoulders to speak of for most of the way, only terrifying drop-offs. If the Navigator's tires ever lost traction on the slippery dirt sections, it would have meant a certain flaming fiery death for all of us.

Below is a picture Mary took with her iPhone during the ascent. She took it upside down, as it happened — the condition of our stomachs at the time.

For a while it seemed as though the road would never end, but it finally did, on top of the mesa, where we were presented with . . . a winter wonderland. An endless plateau covered in snow, dotted with cedars, new snow falling gently on it all.

It was like a vision of peace and grace, granted to us after our ordeal.

I couldn't get this extraordinary experience out of my mind. The next morning I had what felt like a revelation — I felt we had been led supernaturally to the Moki Dugway, where we reenacted, in a sense, the climactic scenes of Wagon Master, when the Mormons take their wagons up the side of a precipitous cliff, where wagons were not meant to go, in order to reach their promised land.

I became convinced that John Ford himself had been riding with us on our climb up the mesa, having decided that we would not just have a leisurely meander up to Moab to gawk at his sublime locations for Wagon Master, but drive right into the heart of the movie. Mystical as it may sound, I think that's exactly what we did.

This September saw two important events in the life of our culture. One of them got a lot of attention, the other didn't. The attention went to the CD release of the remastered Beatles catalogue — an event that was important but in great measure symbolic. It was wonderful to have all those albums sounding so good — as good as CDs probably can sound — but it's not like the music had been unavailable before the remasters. The remasters were primarily an excuse to listen to it all again and begin thinking about The Beatles' place in history.

A week after the remastered Beatles catalogue was released, John Ford's Wagon Master appeared for the first time on DVD in the U. S. Its arrival didn't cause much of a stir. Wagon Master was a film that had been very hard to see, and for that reason lingered at edge of Ford's body of work, greatly admired by some but generally considered a second-rank effort in the Ford canon. The reviews of the DVD I've run across online, very respectful for the most part, have confirmed this status — the consensus seems to be that it's good to have the movie on DVD at last, even though its appearance is not likely to spark a major critical reevaluation, placing it in the same league as The Searchers, for example.

However, that's just where it belongs. Wagon Master may well be Ford's greatest film, his most perfectly realized film and, in some ways, his most radical film.

It is certainly one of his most personal films and he himself often cited it, sometimes in company with The Sun Shines Bright, as his favorite film. Harry Carey, Jr., who starred in the film with Ben Johnson, Ward Bond and Joanne Dru, said that Ford was in a good mood the whole time he was making it. This was not usual for Ford, to put it mildly — he had a vicious streak that almost always found its way onto the sets of his movies. It was nowhere in evidence on the set of Wagon Master, which Ford banged out in 30 days in something resembling a state of bliss.

One can imagine a few personal reasons for this. It was a low-budget film, made by his own independent production company, and it had no name stars in it. Ford had no executives on his back up there in Moab, Utah, where he shot most of it, and no star egos to keep in check. He made this film with almost complete freedom from studio interference.

Ford said that he fought a thousand battles with the studios in his career and lost all of them. Occasionally, with a studio head like Daryl Zanuck, he was fighting with someone he admired, grudgingly. But look at the changes Zanuck made to My Darling Clementine between the surviving preview version and the release version. They all coarsen the film, diminish its poetry and its subtlety. They may or may not have been wise changes from a commercial standpoint — we will never know — but the film would have been a greater work of art if Zanuck had kept his hands off of it.

Wagon Master is one of the only Hollywood films I can think of which does not open with a corporate logo. It's not marked up front with the brand of the nasty little men who controlled Hollywood by the simple expedient of exercising a virtual monopoly over film distribution in America. (If you think any of those guys would have survived six months in a free market for movies, you just haven't looked past the glamor of their artificially-created power.)

Instead of a corporate logo, Wagon Master opens with a dark image of a robbery in a small office, superimposed over a wanted poster of the robbers (above) — the Cleggs, a family of outlaws who will figure importantly in the story we're about to see. There's probably an ironic joke in this. When Ford tried to create his independent production company, he was robbed blind by the studios he still depended on for distribution — and there was nothing he could do about it. Working on a small profit margin, Ford's company eventually failed because the financial edge it needed was stolen from him by the studios he was trying to break free from.

So Wagon Master is brought to you by the Cleggs — like every other Hollywood movie from the era. Dumb, brutal thugs, the Cleggs will come a beggin' to the good folks of the film's wagon train, sponging off them, feigning gratitude, just waiting for the moment when they can exercise their ugly form of control. You can see the good folks of the wagon train as the people in Hollywood who actually did the work there, who actually made the films there, for the benefit of the dimwits with the guns. How delightful it must have been for Ford to set the dimwits up in this way, all the while knowing that in the story of this film, at least, they would get their comeuppance, and then some. No wonder he was in a good mood out there on the frontier, telling this tale.

But even if this joke is embedded in Wagon Master it's not finally what the film is about. It's a lot deeper than that, a lot more complex. On one level it's about the way men and horses move through landscapes — about the way horses behave when they're pulling wagons through rivers, about the way Ben Johnson sits a horse. The way Ben Johnson sits a horse is at the very heart of the film.

Johnson's grace in the saddle is every bit as magical as Fred Astaire's casual defiance of gravity in his dances, and every bit as cinematic. It helps to have some familiarity with riding to appreciate it. On the commentary for the new DVD, Harry Carey, Jr., himself a fine horseman, keeps crying out with pleasure at Johnson's way with a horse. (“That's how you get on a horse!” Carey will shout occasionally. “That's how you get on a horse!”) But even if you've never been close enough to a horse to smell it, you can feel the magic of what Johnson is doing — just as you can feel the magic of Astaire even if you've got two left feet.

As with dance, horsemanship suggests moral values. Treating a horse in a kindly, respectful way parallels the courtly partnership of a great pas de deux. Skill and ease on a horse, the physical virtuosity of it, evoke character, testify to history. Johnson, like Astaire, had the sort of virtuosity which can only be achieved through a lifetime of discipline, a lifetime spent in the saddle or in the practice studio.

Here's something to look for in Wagon Master — a scene where Johnson does his most spectacular riding, fleeing from a band of mounted Navajos. He and his horse traverse rough ground like water flowing over a rocky stream bed. At one point Johnson loses his right rein at a full gallop downhill and leans down to retrieve it like a short-stop scooping up an easy grounder. Johnson once said of a spectacular ride in another Ford film, “I was just a passenger on that one.” This gets close to the mystery of riding — a great horsebacker is always a great passenger, in tune with his mount, with the ground they cover, in tune therefore with the earth but creating new possibilities of movement in space, like a dancer. It is a combination of mastery and surrender, of harmony and challenge, an image of human potential at its extreme limits.

When you see Astaire dance, you know he's going to get the girl in the end. When you see Johnson ride, you know he's going to save the dream of the Mormons migrating west.

You know he's going to get the girl, too. The “love story” between Johnson and Dru, playing a slightly worn showgirl, is one of the deepest in all of Ford's work, and one of the sexiest, though Ford doesn't even give them a fade-out kiss. It's all about the gracious courtship of a woman who has long ago given up dreams of gracious courtship. It's about her surprise at this, and mistrust of it, and final surrender.

It's a romance that plays out in physical terms, in the way he moves and the way she moves — a complicated sexual display in which every casual touch or glance is erotically charged. In the last two-shot of the couple, riding on the seat of a wagon, nothing has been spoken about what's ahead for them, but you can see it in their eyes. It's almost indecent, what you see in their eyes.

Wagon Master is a film made up of closely observed physical phenomena which Ford has somehow invested with moral and spiritual meaning. Good and evil don't need to be given symbolic markers — we see them at work without masks, without name-tags. In all of art, I think only Tolstoy, in War and Peace, got anywhere close to this effect.

In Wagon Master, Ford shot a thoroughly convincing documentary about the world of spirit . . . about spirit made flesh, literally. Other films have tried to do this, but Wagon Master makes even the best of them, like The Diary Of A Country Priest, look ham-handed by comparison.

The ending of Wagon Master is as odd and unconventional as its opening. Just as the settlers get within sight of their promised land the narrative deconstructs itself — we are presented with a montage of discontinuous shots. Some seem to show the characters riding on to a new life, others are shots from earlier in the film. Time dissolves, the wagon train moves on, in the mystical dimension the film has conjured from its meticulous rendering of actualités.

To put it very bluntly, as Ford might have, to get us off the scent of his piety and faith, Wagon Master is a God-damned miracle.

I just finished watching the new DVD of John Ford's Wagon Master — a beautiful transfer of a very beautiful film. I'm speaking from a place of unexpected emotion at the moment, but I think what I'm about to say is true all the same — Wagon Master is John Ford's greatest film.

More on this subject soon . . .