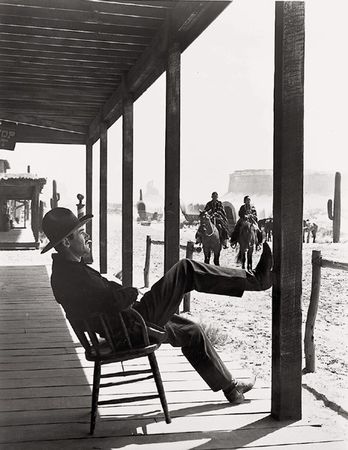

Recently, watching an excellent documentary about Buffalo Bill Cody, from the PBS American Experience series, an image jumped out at me. It was part of the relatively rare surviving film depicting Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show in performance. It depicted one of the show’s most popular episodes — “The Attack On the Settler’s Cabin”. A fairly small, square replica of a cabin was set up in the middle of the arena. Performers portraying a pioneer family would defend this from an attack by mounted Indians until Buffalo Bill and his trusty cowboy compadres rode in to rescue them. (The photograph of the cabin above gives a sense of its stage-set quality but not of its isolation in the emptied arena, conveyed in the documentary film footage.)

The precise iconography of the image, and not just the dramatic situation, seemed oddly familiar, and I quickly realized where I had seen it before — in the films of D. W. Griffith. Several times — in The Battle At Elderbush Gulch and in The Birth Of A Nation, for example — Griffith had staged an attack on an isolated cabin that evoked the staging in Buffalo Bill’s arena. Griffith would start with a long shot of a small, square cabin in a valley that had the theatrical quality of an arena. He would cut back repeatedly to this long shot during the course of the attack.

Of course, an attack on an isolated cabin would become a staple of Western films, as would most of the episodes of Buffalo Bill’s show — the attack on the wagon train, the ambush of the Deadwood Stage, the heroics of the Pony Express Rider, the buffalo hunt, Custer’s (or some other cavalry leader’s) last stand against swarming Indians — but Griffith’s iconography was very distinctive and rarely reproduced, the cabin looking too small to hold the defenders later revealed to be inside it, set in the middle of a topographical amphitheater, seen from above, as though from some ideal vantage in the bleachers.

Note also (in the frame above from The Battle At Elderbush Gulch) the curious isolation of the cabin, with none of the outbuildings or stock pens one would expect to see surrounding a real pioneer home. The cabin has something of the feel of a set, or a prop, as did Bill’s cabin. Contrast this with the remote homestead attacked by Indians in The Searchers, which looks like a working ranch complex.

I’m sure that Griffith was echoing, consciously or unconsciously, something he’d witnessed in a performance of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West — augmenting the theatrical spectacle with the photographic authority of a movie shot on a real location. The reality of the location was important — it was part of what made all Wild West arena-show recreations seem old-fashioned to the growing audience of 20th-Century moviegoers — but the evocation of Buffalo Bill’s show was also important, because this was where so many moviegoers had gotten their first thrilling glimpse of the mythic West that Bill had done so much to create or consolidate in the world’s imagination.