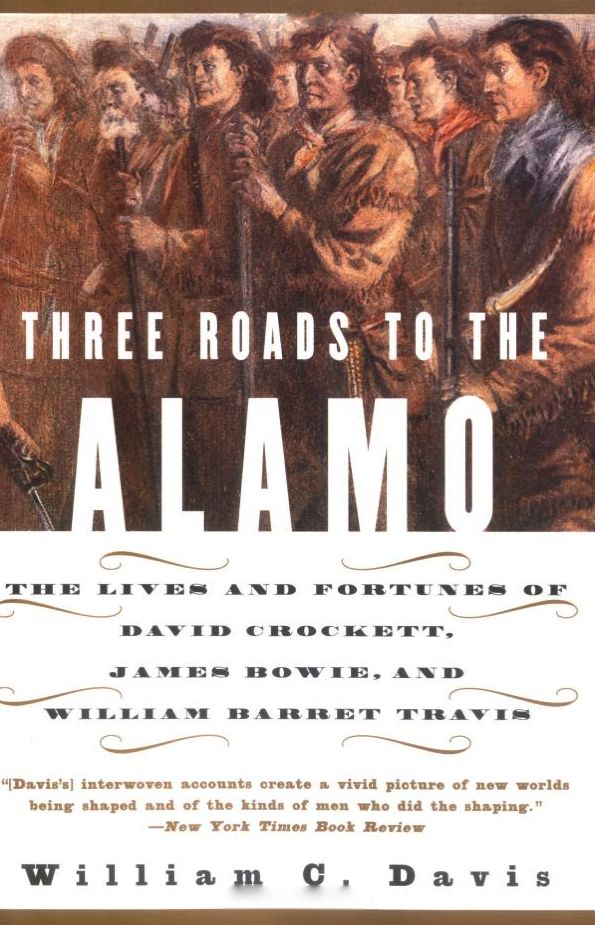

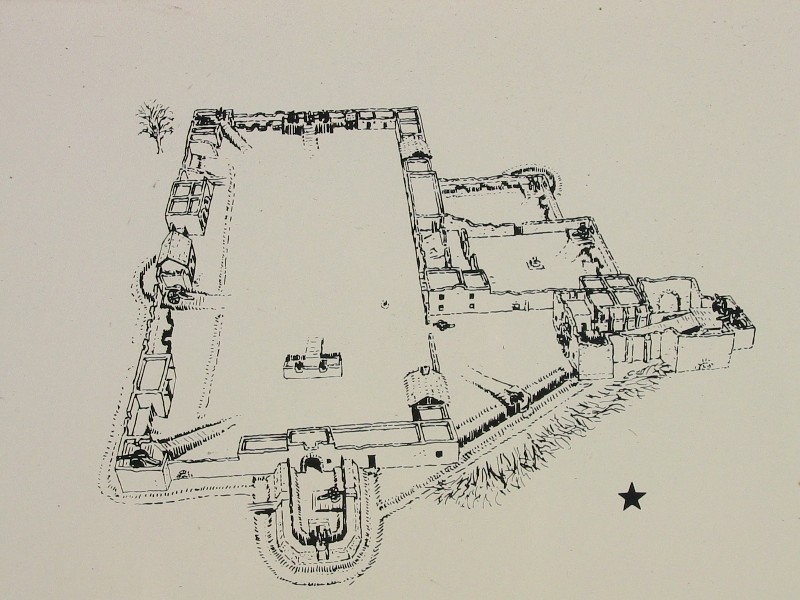

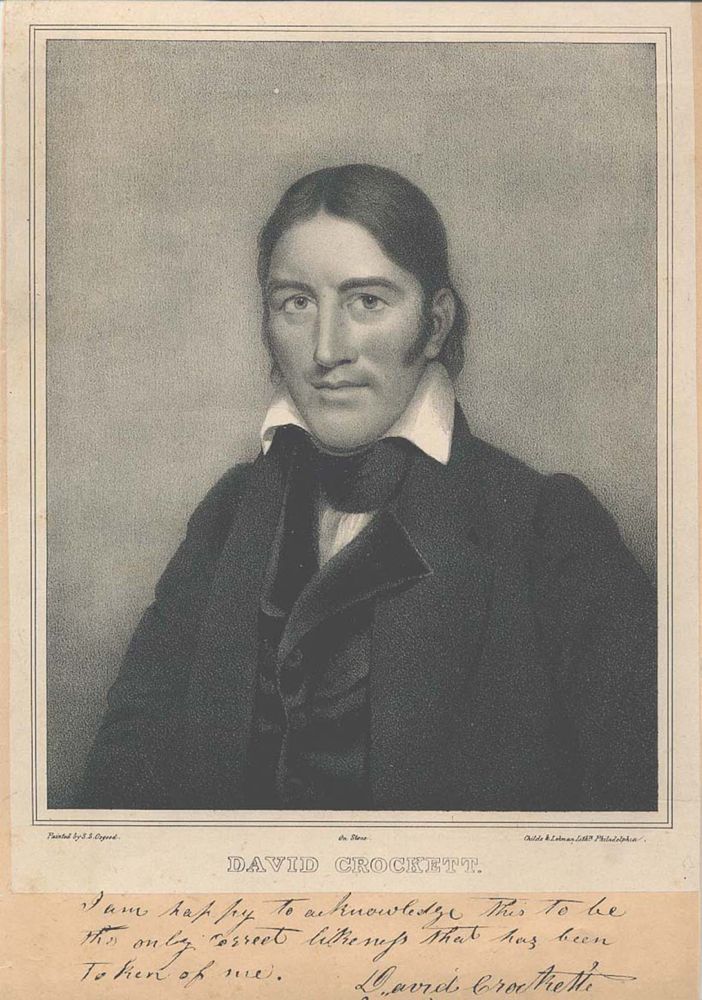

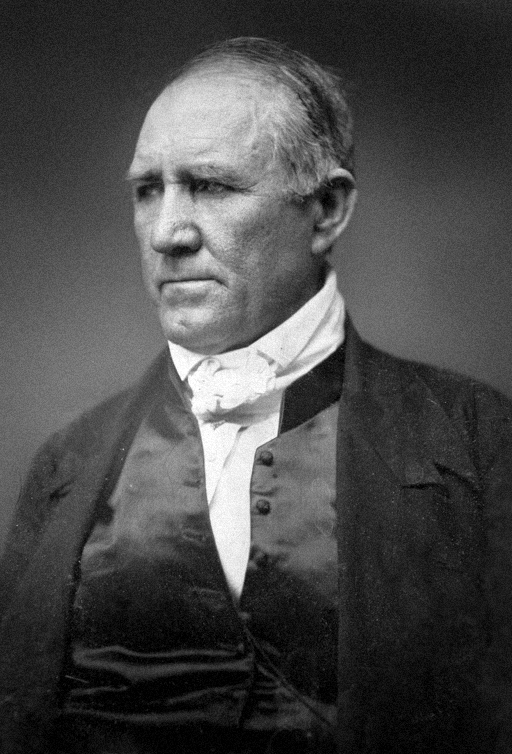

This is an extremely interesting combined biography of David Crockett, James Bowie and William Barret Travis. It follows their lives up to the moment they all found themselves with two hundred or so others inside the Alamo compound early in 1836, prepared to defend it against a Mexican army ten times as large.

Dying there, when they could easily have chosen not to make the stand, they became martyrs to liberty, in some sense transcending their troubled pasts, living on as myths.

That they were all flawed men, impelled out to the Texas frontier by humiliating failures, for motives both idealistic and self-serving, doesn’t really lessen their stature as American icons — in a way it enlarges it, showing how imperfect men can rise to great occasions.

The book is invaluable as a survey of the American frontier in the 1820s and 1830s, a rambunctious time when the common man, under the inspiration of Andrew Jackson, took hold of the reins of America and illuminated some of the fundamental contradictions of the American character.

Personal honesty and honor counted for much, except when big schemes were afoot, in which case skulduggery was tolerated, even admired. Notions of liberty were inextricable from notions of gain, a capacity for sacrifice inextricable from a capacity to bully and bamboozle.

The moral landscape of the frontier was as wild as the physical landscape — anything was possible, reinvention of the self and a renewal of one’s dreams lay just beyond the next river, the next mountain range.

Dying at the Alamo seemed to confirm that the journey for Crockett, for Bowie, for Travis, had always had a noble destination somewhere up the trail — a reassurance that America needed back then, and still needs.