Category Archives: The West

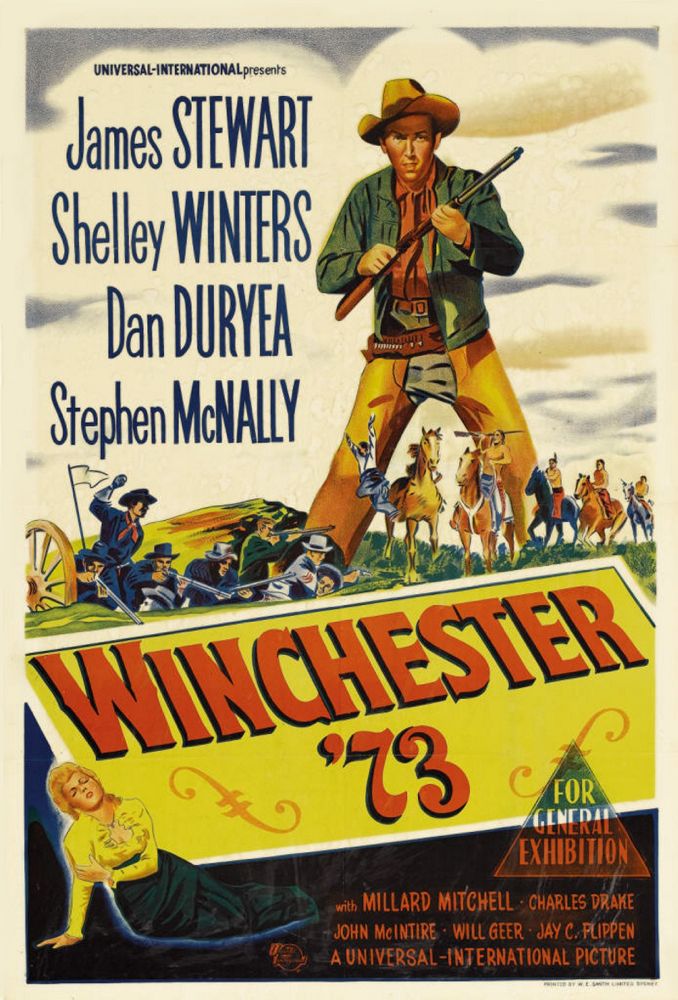

A WESTERN MOVIE POSTER FOR TODAY

A WESTERN MOVIE POSTER FOR TODAY

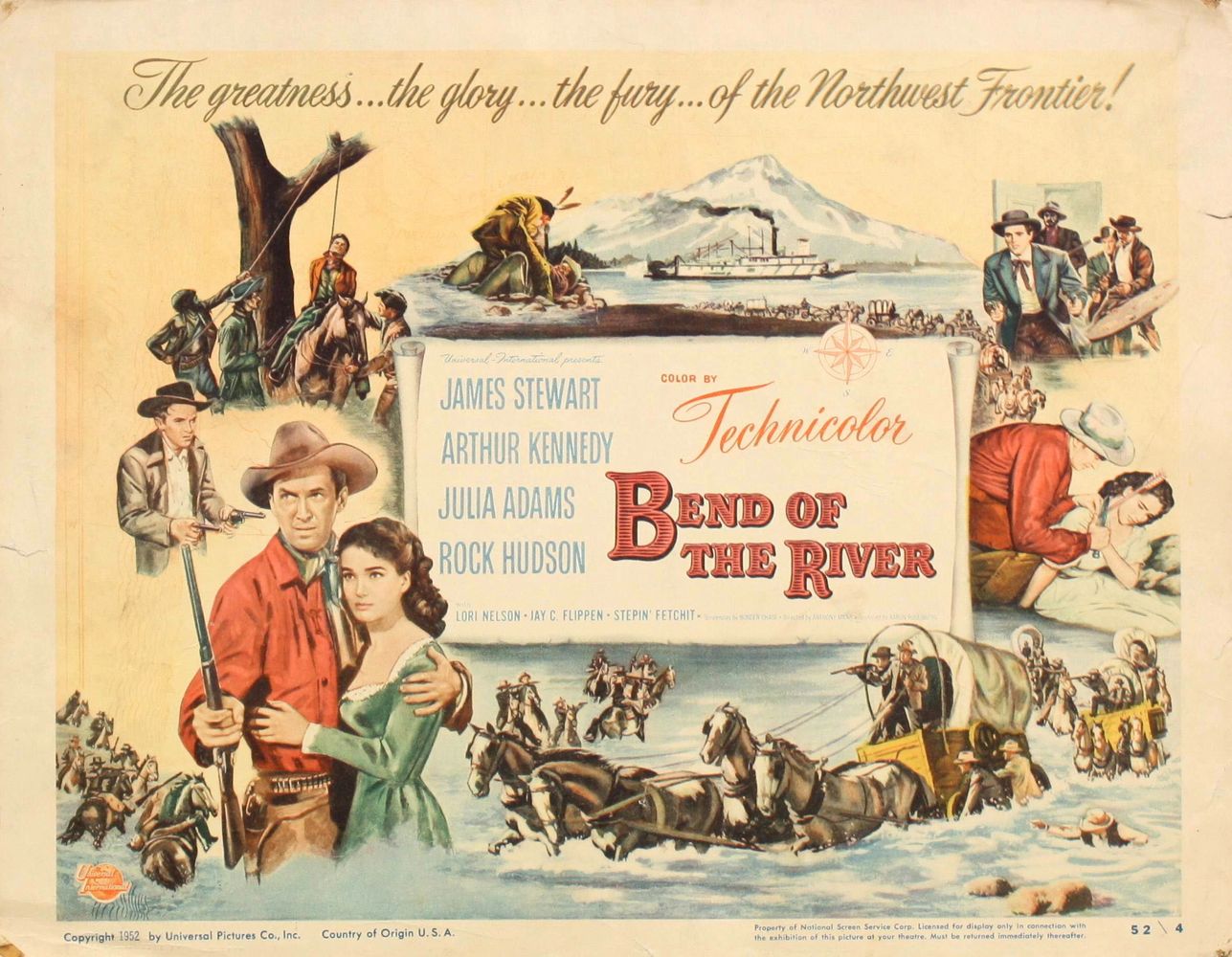

A WESTERN MOVIE LOBBY CARD FOR TODAY

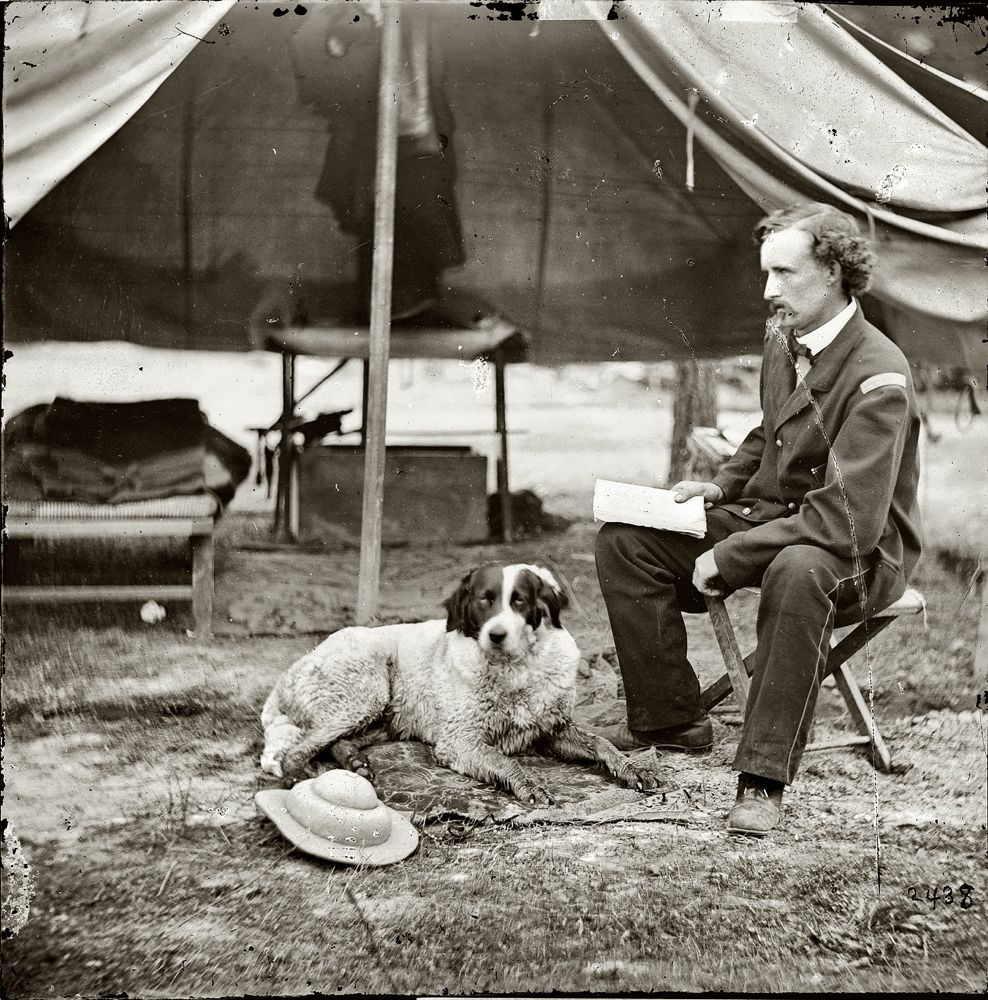

YOUNG CUSTER

LIFE ON THE FRONTIER

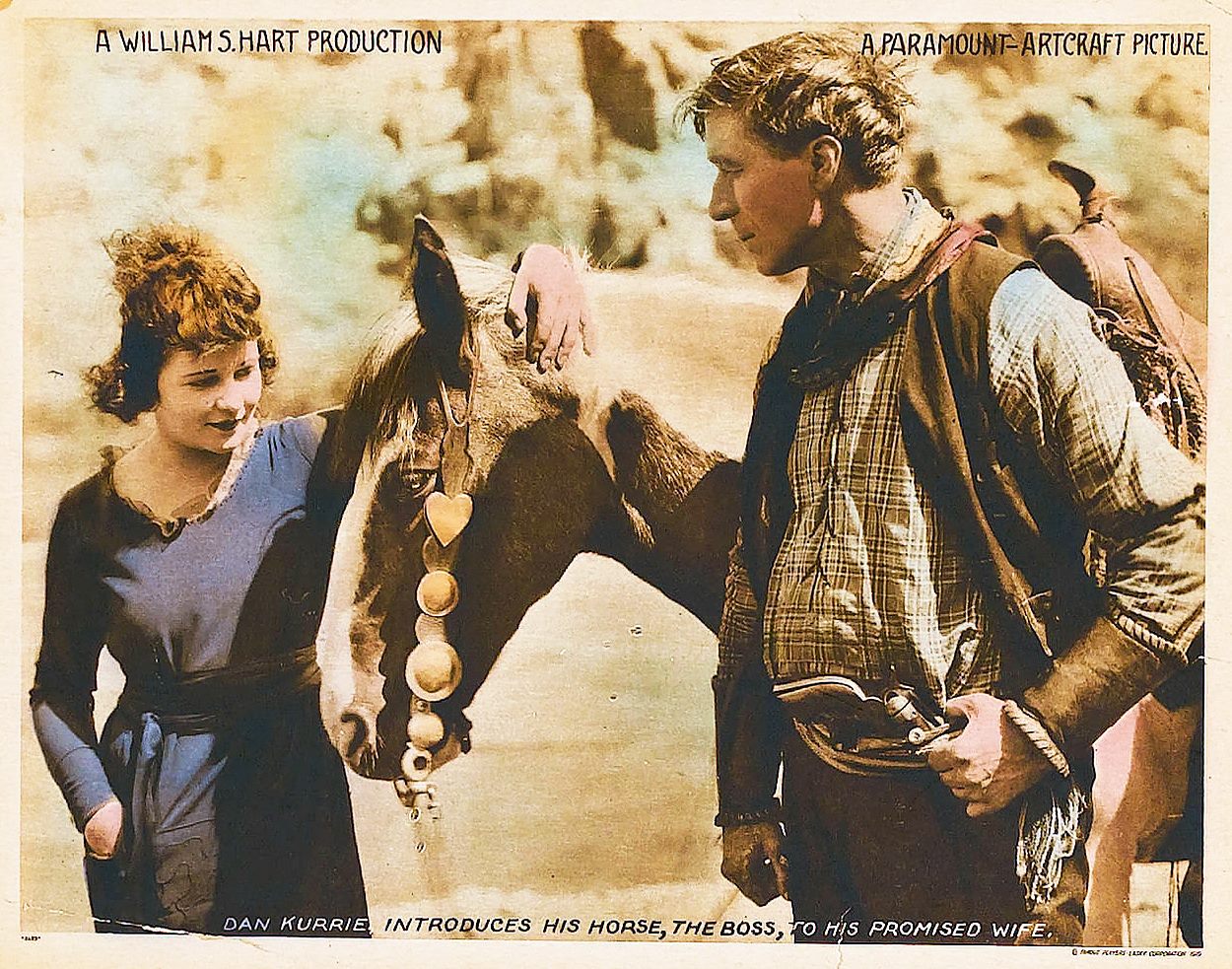

A SILENT WESTERN LOBBY CARD FOR TODAY

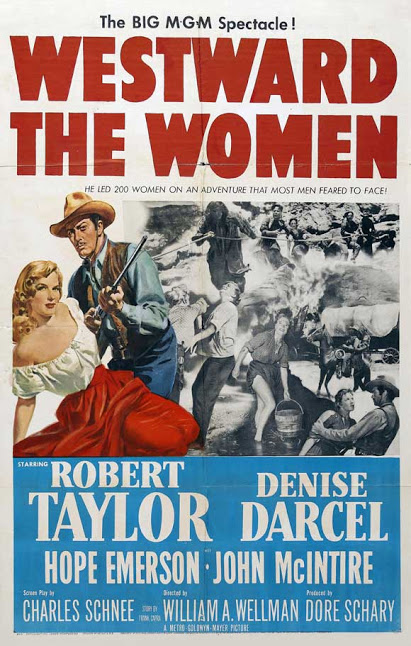

WESTWARD THE WOMEN

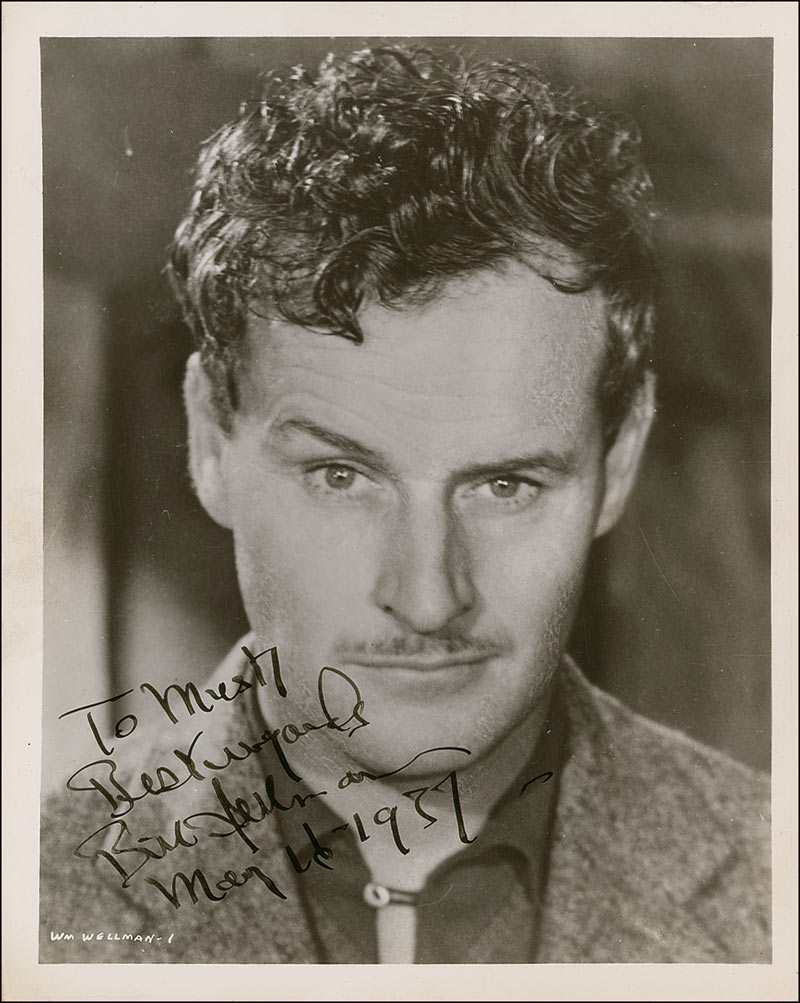

A lot of Hollywood directors who earned their spurs in the silent era and survived into the sound era had backgrounds far removed from the picture business. A number of them were mechanics, race car drivers, pilots. They were what used to be called manly men, and they brought a traditional masculine perspective to their work in action films. I’m talking about guys like William Wellman, Howard Hawks and Victor Fleming.

Curiously, these men were also exceptionally skilled in presenting strong women on screen — they seemed to be fascinated and not in the least bit threatened by strong women. Victor Fleming, who directed Gone With the Wind and The Wizard Of Oz, both anchored by strong female leads, was also the first director to let Clara Bow do her thing on screen in the silent film Mantrap, in which she ran sexual circles around her male leads and laughed at them while she was doing it.

Hawks unleashed Hildy Johnson and Sugarpuss O’Shea and Lorelei Lee on equally defenseless males and made us laugh at their invincible power and wit.

In 1951 William Wellman made the very odd Western Westward the Women about a wagon train of mail order brides making a 2000-mile trek from Chicago to California to hook up with prospective mates on the frontier. There are a couple of ex-hookers among them, hoping to turn over a new leaf, but they’re mostly “good women” looking for good husbands.

They’re led by the exceptionally competent but distinctly misogynistic trail guide Buck Wyatt, played by Robert Taylor. He admits up front that only two things in life scare him, and they’re both “good women”. He says he hates women’s cooking, and doesn’t expect much out of his charges except suffering and perseverance. He hires a gang of men to provide for their defense on the journey.

But then most of the men desert the train when Wyatt executes one of them for raping a woman. Wyatt wants to turn back but the women won’t turn back, even if he does. At that moment they become the heroes of the film, and Wyatt watches as they do what needs to be done to get the train through, at first amused, then a little bit awestruck.

The women don’t turn into men. Before they arrive at their destination they insist on stopping so they can make themselves presentable when they meet their future partners. Wyatt doesn’t understand this — it seems a little “girly” after all they’ve been through — but he’s past arguing with them. They’re his equals as trail bosses now.

Yet when the women show up to meet the men they’ve prettied themselves up for, their spokeswoman makes it clear that the women will do the choosing. Their passage across the continent may have been paid for by the men, but the women are in charge of the pairing up — they’ll have the last word on that.

Wellman presents all this with little comment — not making a point of female courage and competence, just showing it. Nor does he patronize the women’s desire to make themselves attractive at the end. He just respects it without judgment — not suggesting that they’ve turned back into “girly girls” but accepting that they’ve always been girly girls, as well as tough characters, as tough as any man. They can work like men, and fight like men, and die like men, but they’re . . . different.

Wellman was a tough guy — he won the Croix de Guerre with two palms flying airplanes in France in WWI. It took a tough man to make a movie like Westward the Women.

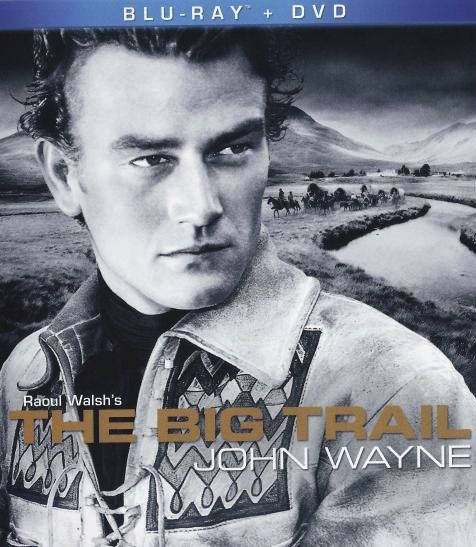

THE BIG TRAIL ON BLU-RAY

Raoul Walsh’s The Big Trail from 1930 is one of the most beautiful movies in the history of cinema. Almost every shot is masterfully composed, lit and choreographed, moving effortlessly between the lyrical and the epic, astonishing at every turn.

It was filmed in an early widescreen process that didn’t catch on but the movie survives in that form, and is now available in a Blu-ray edition that does more than a measure of justice to Walsh’s achievement, which is really amazing. He made one of the first full-scale widescreen films and it’s as elegant and accomplished as any that have followed it, including the widescreen pictures of John Ford and David Lean.

Unfortunately the film was an early talkie, and though the sound recording on a wide variety of exterior locations is technically impressive, the actors deliver their lines in a stilted, declamatory style, perhaps for the benefit of the microphones, which seriously undermines the total effect of the movie. It doesn’t help that their dialogue is clumsy in its own right, very badly written.

Once you get past this flaw, however, you’re treated to a visual feast that’s inexhaustible, a pageant of breathtaking images that are simply unforgettable.

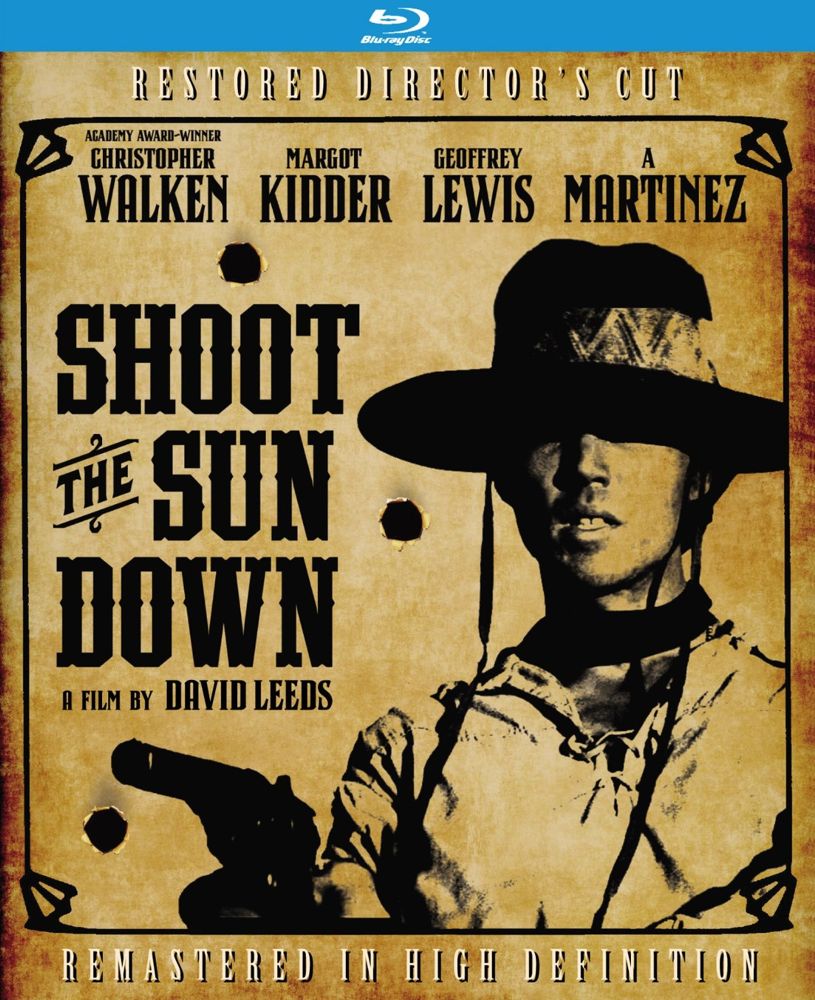

SHOOT THE SUN DOWN

This quirky Western from 1978 got a limited theatrical release when it first came out and then disappeared from sight but has recently been released on Blu-ray by Kino. It’s sort of an American version of a Spaghetti Western, slightly tongue-in-cheek and occasionally verging on the surreal, with a score that rather deliberately mimics Ennio Morricone’s work for Sergio Leone.

Christopher Walken, looking impossibly young and pretty, does a fair impersonation of The Man With No Name, though his character does have a name of sorts here — Mr. Rainbow. Margot Kidder, looking equally young and pretty, plays the female lead.

The narrative meanders off the trail aimlessly from time to time, and the tale never gathers much momentum, but the film is always engaging, primarily because Walken and Kidder are so engaging. It was handsomely shot, apart from a few too many zooms, by the estimable Michael Chapman, uncredited on the film for some reason.

If you like Westerns you’ll enjoy it, and even if you don’t like Westerns you’ll probably find it fascinating for its off-beat charm and imagination.

JOHN WAYNE

A MAXFIELD PARRISH FOR TODAY

ESSENTIAL

To my mind, this is one of the greatest Westerns ever made, all the more amazing for being made in the 90s, when Westerns of any kind were few and far between.

As I’ve written before, I think all truly great Westerns deal with the themes of shame, honor and redemption. They’re parables on the subject of being a moral person, usually a moral man, a worthy man. Because its setting is the American frontier, the genre is often seen, and sometimes dismissed, as the embodiment of a national myth, a myth about the nature of America itself, and it’s partly that, but it works on deeper and more universal levels, too, which is why it has been embraced internationally.

It’s a genre about achieving full manhood, and sometimes full womanhood, seen as states of moral maturity.

Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven is an example of how dark and morally problematic a Western can be and still stay within the traditional bounds of the genre. Its protagonist William Munny, a reformed drunk and killer, has put his outlaw ways behind him under the influence of a good woman — but she’s dead and has left him with two small children to raise.

He’s lured into doing one last job as a gun for hire, which he takes on so he can give his kids a new start somewhere far from their failing farm. But he’s also willing to take the job because it involves helping a group of prostitutes get revenge on a couple of cowboys who have cut up the face of one of their number. Munny has killed innocent women in his day, in the course of committing crimes, but has experienced profound remorse for this. Coming to the aid of the powerless women feels on some level at least like a means of redemption.

But things don’t turn out to be so simple. The cut whore for whom revenge is sought doesn’t seem all that passionate about revenge herself. One of the cowboys who wronged her is not such a bad guy. Munny’s two cohorts in the killing for hire become disgusted by the job.

The real villains of the piece turn out to be a sadistic sheriff and an exploitative brothel keeper, to whom Munny will eventually deliver justice — escaping with his moral code compromised in some respects, honored in others. There is a confused, bewildered nobility in the man which triumphs in the end . . . but just barely.

Eastwood’s film is expertly crafted and acted, complex and disturbing and inspiring all at once. It’s a great work of art. The Blu-ray of Unforgiven belongs in the home of every fan of the movies.

GALLANTRY

In Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven, when William Munny tries to get his old friend Ned Logan to partner up with him for a hired killing, Logan is uninterested. Like Munny, he’s left his outlaw days behind, and can’t see the point in killing a man unless it involves a personal grudge — certainly not for the usual crimes, rustling or cheating at cards or insolence.

But when Munny says the men he’s been hired to kill cut up a woman, Logan’s attitude changes — he’s shocked and outraged. “Well then, ” he says, “I guess they got it coming.” He signs on for the job with Munny, who seems to feel the same about the deed they’ve been hired to avenge, although Munny himself has the lives of innocent women on his conscience from his days as a drunken thug. Clearly something in him has changed.

They’re doing it for the money, at bottom, but the horror of cutting up a woman takes the moral sting out of it for both of them.

I like to think that if they were told a scumbag like Pike Bishop, leader of The Wild Bunch, ordered the murder of an unarmed woman during the robbery of a railroad office, they’d feel the same. They wouldn’t ride off to avenge the murder for the sake of justice alone — they’re not knights errant — but they’d feel entitled to take money to kill Bishop, because he’s got it coming.

This is the difference between real men, however damaged they may be, and frontier scum like Bishop — an innate sense of gallantry and decency towards women that years on the wrong side of the law can’t erase.

Click on the images to enlarge.

BAD COMPANY

Robert Benton’s first directorial effort, Bad Company, from 1972, is a bad film and a bad Western, too. It’s one of those revisionist oaters from the 70s which takes delight in deconstructing the myth of the frontier, showing it as a sordid and depressing place.

It concerns a gang of young men who light out for the territory during the Civil War, to find fame and fortune and/or evade getting drafted into the Union army. It takes forever to get them moving west, in a long prelude to the actual adventure which mostly involves their cute antics as petty thieves.

It proceeds thereafter in a series of vignettes — robbing farmyards, getting robbed by bandits. Some of these episodes are involving, some repetitive. There’s one really well done scene involving a running shootout in a forest filled with leafless trees.

The dialogue feels synthetic throughout, modeled inexpertly on the vernacular style of Mark Twain.

By the end, the two main protagonists have graduated from a life of petty thievery to a life of armed robbery. So much for the American Dream. So much for the sodbusters who turned the desolate plains into a breadbasket for the world.

The film’s one shining virtue is its cinematography, by the late Gordon Willis, who conveys a vision of the plains that is both beautiful and forbidding. It’s the only real reason to watch the film but, Gordon Willis being Gordon Willis, it’s reason enough.