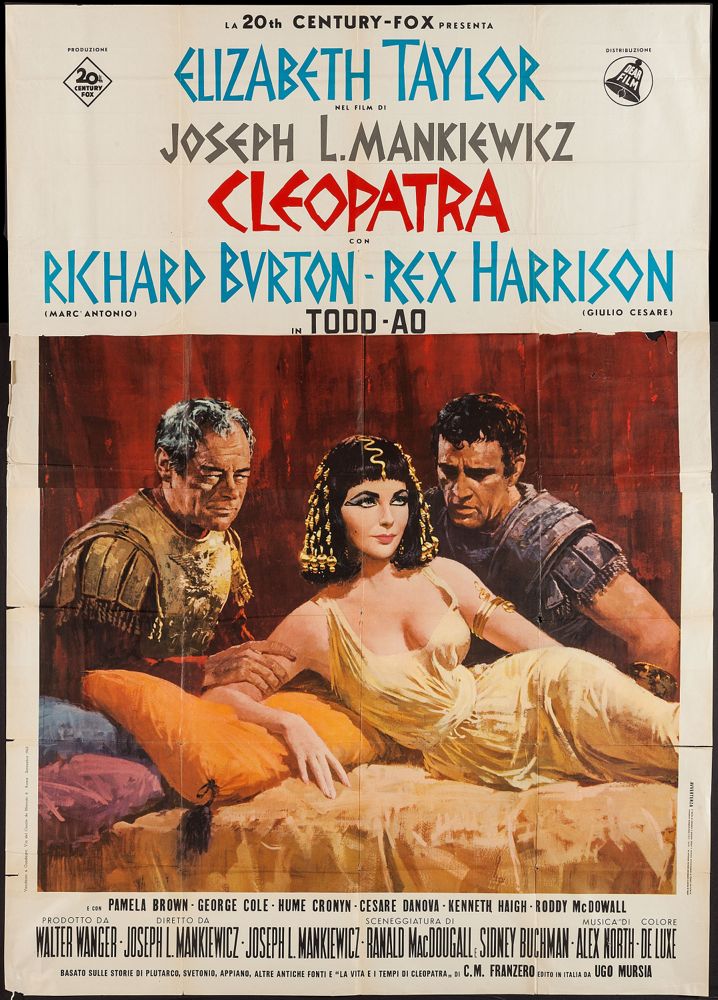

A MOVIE POSTER FOR TODAY

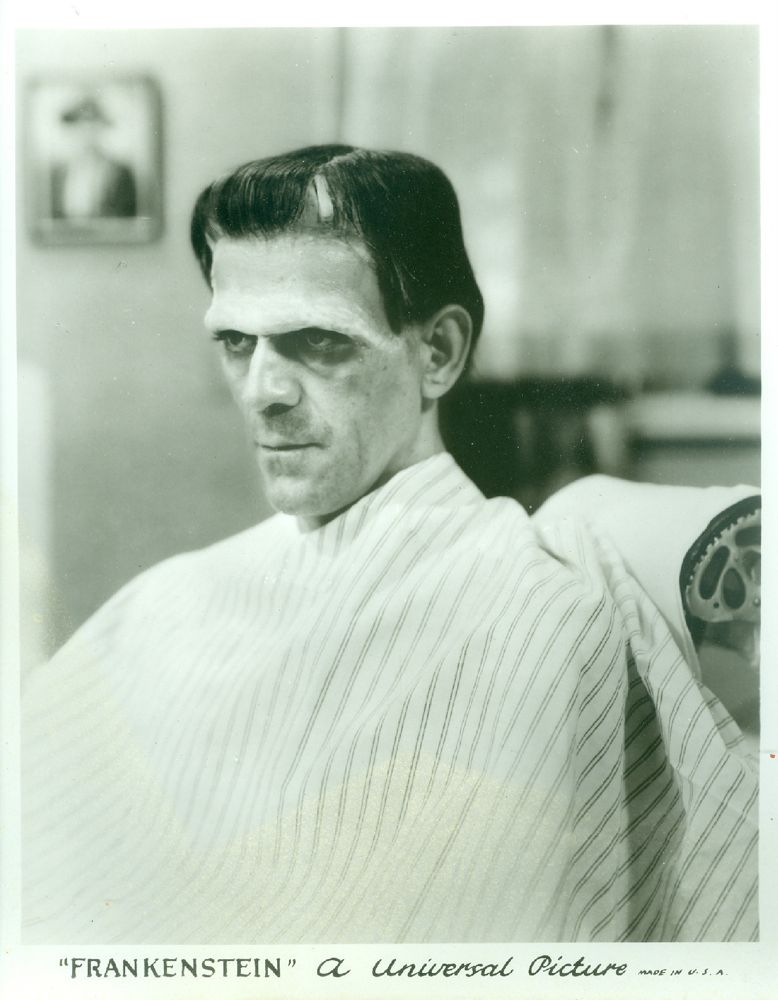

DRIVE-IN

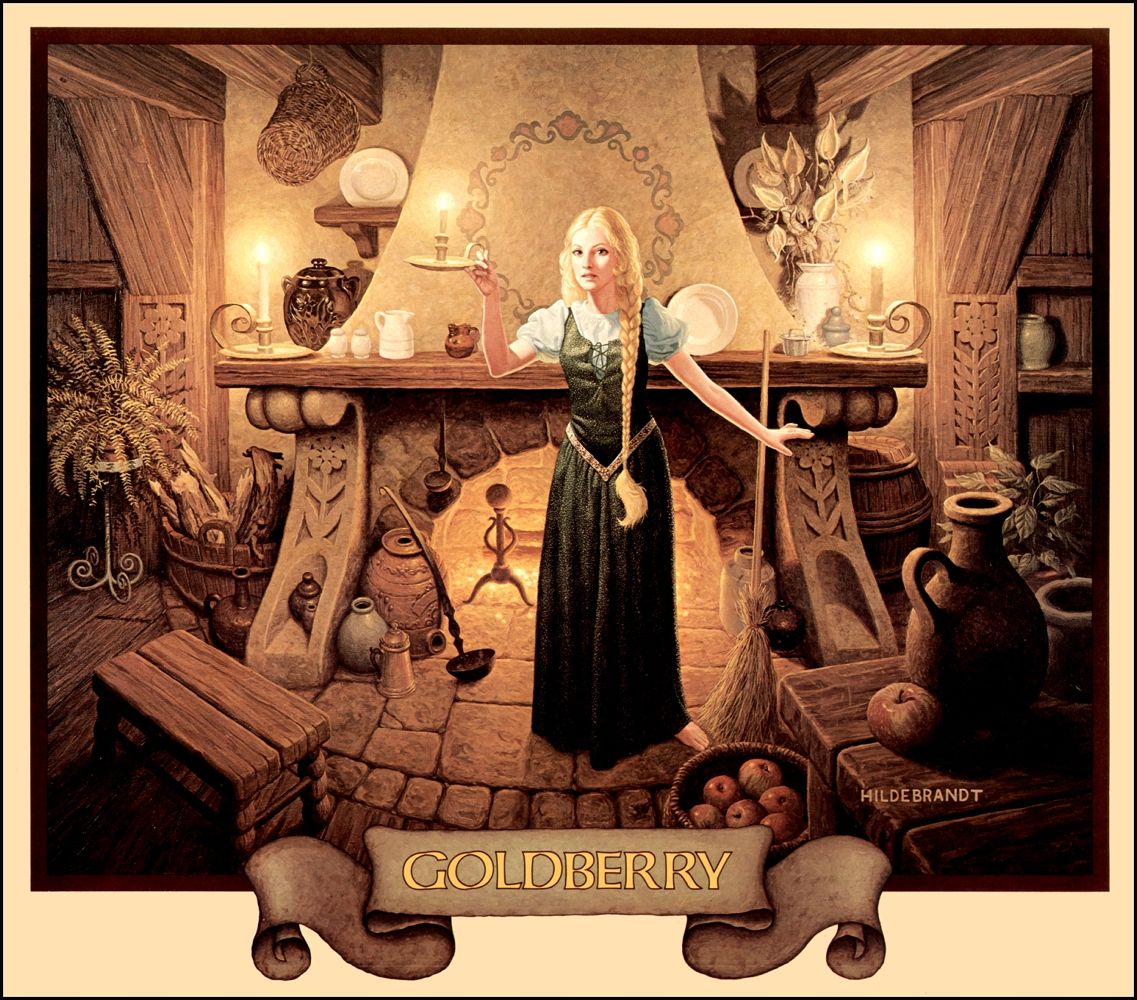

A HILDEBRANDT FOR TODAY

JANTZEN BATHING SUITS

CLEOPATRA (1963)

Joseph Mankiewicz’s Cleopatra, from 1963, has a terrible reputation, and it’s richly deserved. It suffers primarily from the sin of good taste — from creatives choices meant to avoid excessive vulgarity, to suggest sophistication and intellect. God forbid! These are the last virtues one wants from an historical sword-and-toga epic. The Egyptian and Land Of the Pharaohs, stupendously vulgar movies, seem like great works of art compared to the vapid modesty of Cleopatra.

Mankiewicz was a decent writer but a stodgy director, good with actors but cinematically boring. He was the worst sort of director to assign to a troubled production like Cleopatra, which needed the steady hand of a studio veteran but also some style, some visual élan.

Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton were apparently having a lot of fun off-screen during the shooting of Cleopatra, but don’t seem to have had any at all while the cameras were rolling. In the film, the chemistry between them is non-existent.

The narrative is plodding, the dialogue is stuffy, the performances are, for the most part, perfunctory — although all of the principal players have their moments. The production values dazzle in the new Blu-ray edition, and they are enough to make the film entertaining, well worth a look — compelling the way a spectacular train wreck is compelling, although sadly this train wreck unfolds in excruciatingly slow motion.

Click on the images to enlarge.

IN PROGRESS

PRICKLY PEAR BLOSSOM

AN OBNOXIOUS RELIGION

Paul Zahl talks about Grace, and when Paul Zahl talks about Grace, you need to listen — and by that I don’t mean you ought to listen, I mean you need to listen . . .

STANWYCK, ANYONE?

LET’S FALL IN LOVE

“I could never escape from the bittersweet, lonely, intense world of Harold Arlen.” — Bob Dylan

DEVIL IN A BLUE DRESS

The idea of sending a black private eye down the mean streets of Raymond Chandler’s Los Angeles might have ended up as a sort of literary stunt, a clever pastiche, but Walter Mosley’s Devil In a Blue Dress is hardly a stunt or a pastiche. It’s a well-crafted, hard-hitting noir thriller, more than worthy of the Chandler tradition.

The protagonist, Easy Rawlins, is a complex character, estranged from the world he moves in not just by an eccentric moral code that harks back to Philip Marlowe’s, but also by his race, which creates moral dilemmas and peculiar forms of jeopardy every time he interacts with white people. There’s no social pleading here — just the facts, ma’am, just the facts.

A finely-tuned plot, marvelous evocations of Los Angeles in 1948 and intriguing ethical ruminations make Devil In a Blue Dress a classic contribution to the hard-boiled detective genre at its best.

EBB TIDE

Bob Dylan on this recording — “I could hear everything in his voice — death, God, the universe, everything.”

WELCOME TO HARD TIMES

E. L. Doctorow’s first novel, Welcome To Hard Times, published in 1960, was a Western. It was, to be sure, a “literary Western”. Doctorow peppered his prose with passages of fancy-pants writin’ and eccentric punctuation, just to make sure readers knew he wasn’t toiling away in the trenches of mere genre. The villain of the piece was often called only “The Bad Man From Bodie”, capitalized in just that way, associated with a band of “Bad Men” — making it clear that he and they were not just men but mythological embodiments of evil.

Still, the tale starts well, setting up the traditional Western themes of shame, honor and redemption in stark and sometimes powerful ways. As the narrative unfolds, Doctorow loosens up a bit and indulges more and more often in deadpan Western humor and frankly entertaining yarn-spinning. He doesn’t exaggerate his fancy-pants style to the lunatic extremes of Cormac McCarthy’s convoluted gobbledygook, and frequently employs spare and direct language that’s enlivened by quirky insights and supple turns of phrase.

The genesis of the book explains a lot about it. Before he devoted himself to fiction-writing, Doctorow worked for a while as a reader for a motion picture company, in the course of which he plowed his way through many Western scripts. In Welcome To Hard Times, he set out to write a parody Western, but got caught up in his own story and in the tradition and switched to a different strategy — reclaiming the Western as a literary genre.

It was a pompous and patronizing ambition. Elmore Leonard, a much greater writer than Doctorow, was still writing Westerns when Doctorow was writing Welcome To Hard Times. The Western didn’t need to be reclaimed for literature as much as it needed to be recognized as literature.

The book’s parodic roots account for the humor of the work, Doctorow’s familiarity with the genre accounts for its mooring in the traditions of the Western, while the author’s sense of being above the genre accounts for the occasional pretentiousness of the style.

Sadly, Doctorow veers disastrously into “literature” at the book’s conclusion, into an apocalyptic and nihilistic climax that wrenches the tale entirely out of the Western genre, mocking the very idea of redemption. What might have been a respectable contribution to Western fiction becomes instead a fairly meaningless and churlish comment on the tradition. It’s the literary equivalent of shooting someone in the back.