It would not be an exaggeration to call The Virginian, by Owen Wister, from 1902, the most important work of Western fiction ever published. It almost singehandedly made the Western novel respectable and almost singlehandedly created the modern myth of the cowboy as a kind of knight errant of the frontier.

The novel was part of a larger cultural movement in America which sought to understand the meaning of the frontier, and its conquest, in the life of nation. In 1890, the U. S. Census Bureau had announced the end of the frontier — meaning that there were no longer large habitable areas of the country untouched by settlement. An era in American history was coming to a close and the moment inspired a wave of nostalgia and reflection. The crusade to preserve wilderness regions intensified and the colorful legends of frontier life started to become codified into mythic conventions.

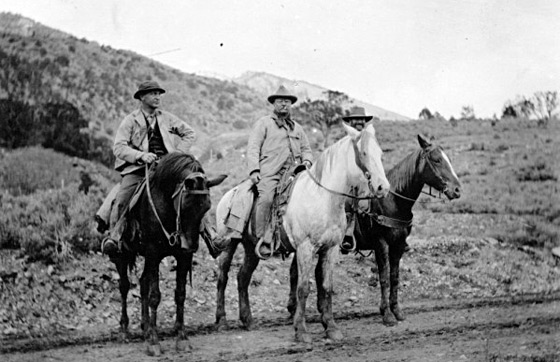

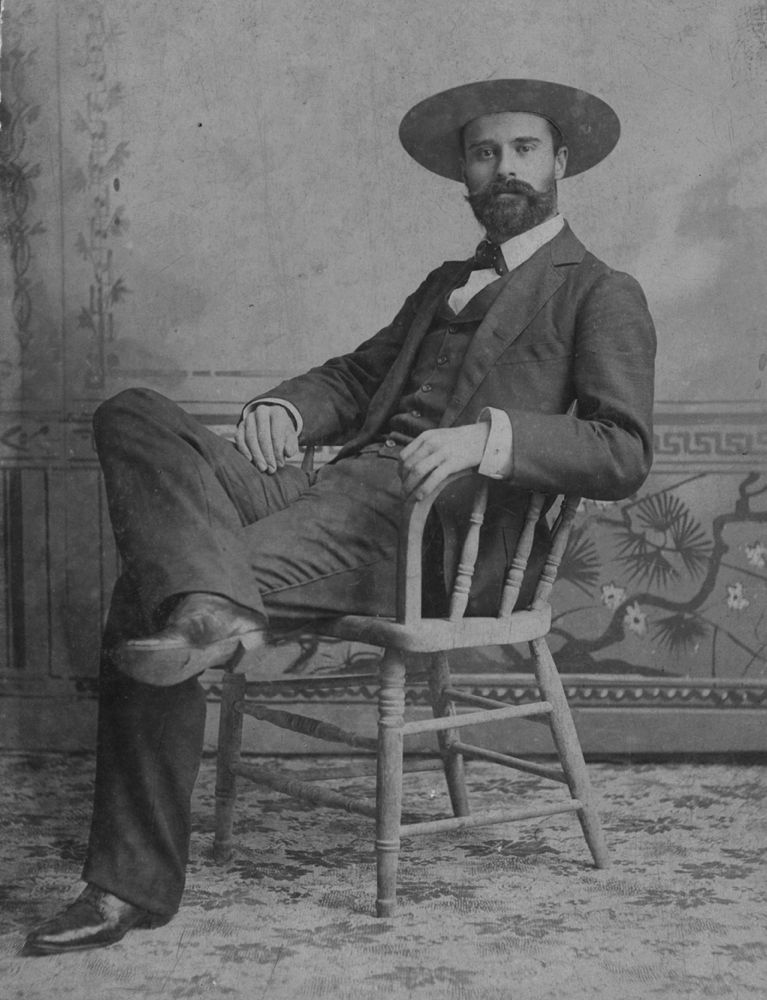

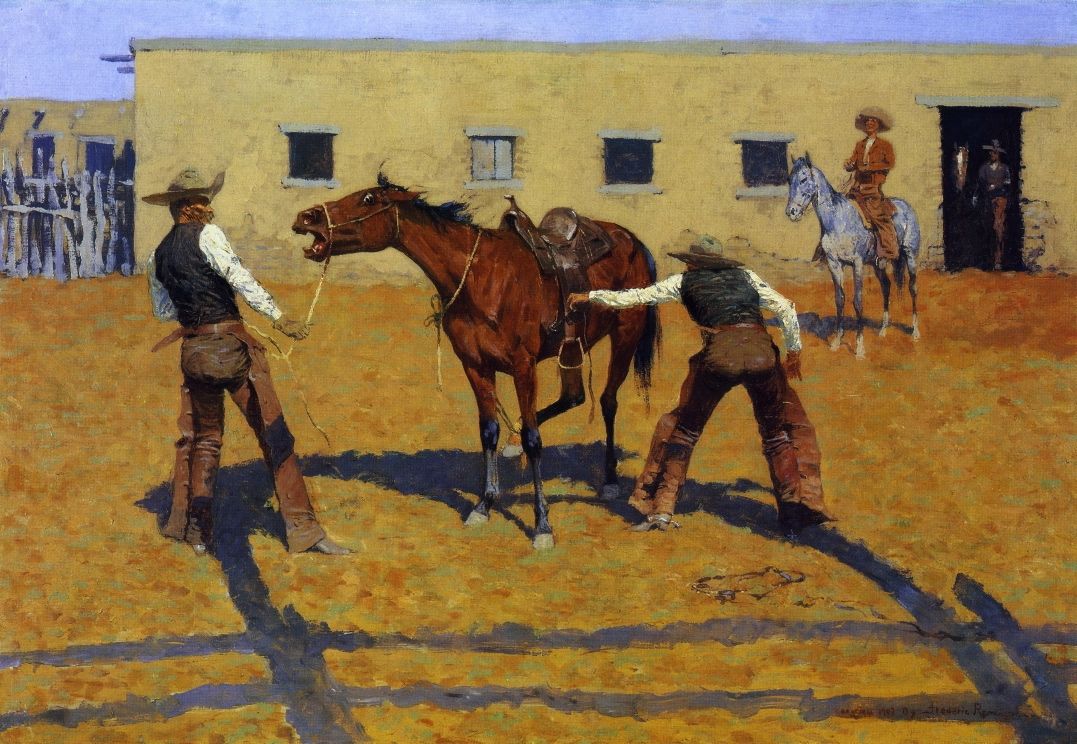

Theodore Roosevelt’s memoirs of his various Western adventures, ranching and hunting, published in the decades preceding The Virginian, had contributed to his national reputation as a quintessential American figure. The Western drawings and paintings of Frederic Remington (a friend of Wister’s who illustrated one of Roosevelt’s Western memoirs when it was serialized in a magazine) along with those of Charles Russell were widely reproduced.

It was Buffalo Bill’s Wild West (above) that gave this cultural trend its most sensational dramatic and visual expression, which the movies would eventually appropriate and expand on, but it was Wister’s book which inaugurated the new literature associated with the trend, one very different from the lurid exaggerations of the 19th-Century dime-novel narratives.

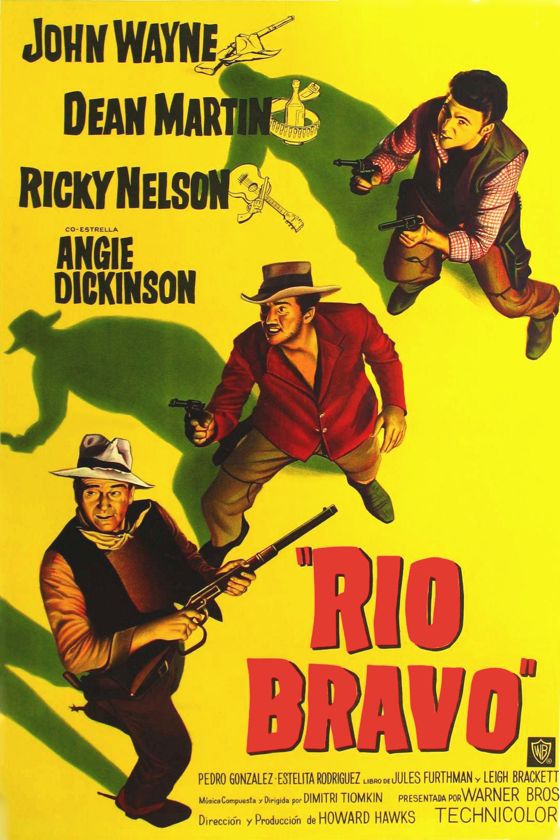

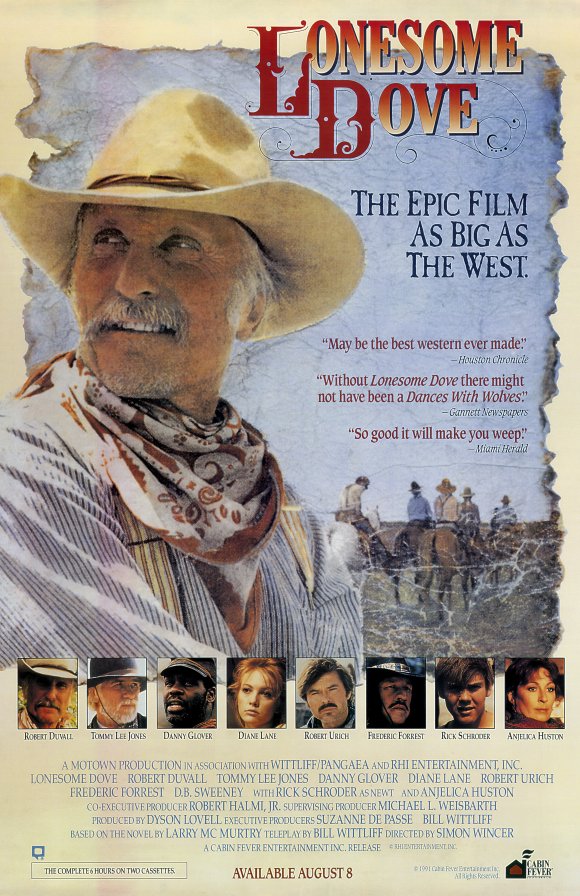

The Virginian is surprisingly readable today. It’s written in a breezy, genial style, and because it portrays a way of life in 19th-Century Wyoming that was already disappearing in 1902, its quaint Victorian mores seem more nostalgic than dated. Its celebration of a simple, decent, gallant manhood informed Western literature and movies for generations — the book has been adapted for the screen six times (that’s Gary Cooper above in one of the adaptations) — and remains appealing in our own time.

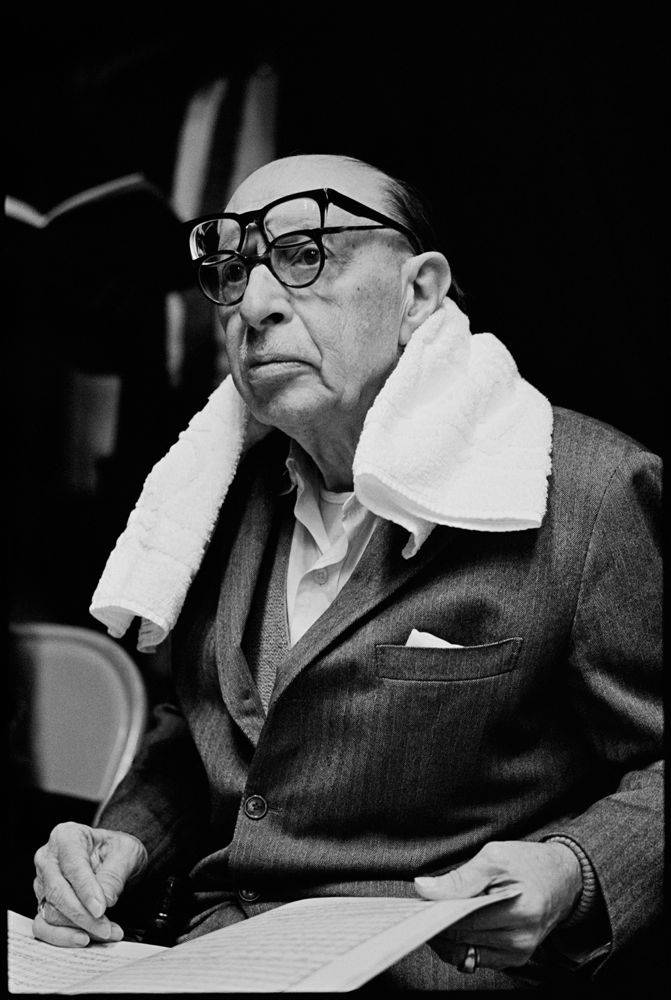

Ernest Hemingway’s post-WWI investigation of manhood is vested with more doubt and angst than Wister’s, but owes something to it. Hemingway loved popular Western fiction, and he and Wister were friends. You might say that Hemingway tried to imagine Wister’s Virginian as a veteran of the wars of the 20th Century, wondering what might be left of him and his simple, gracious virility after passing through those epic soul-shattering catastrophes.