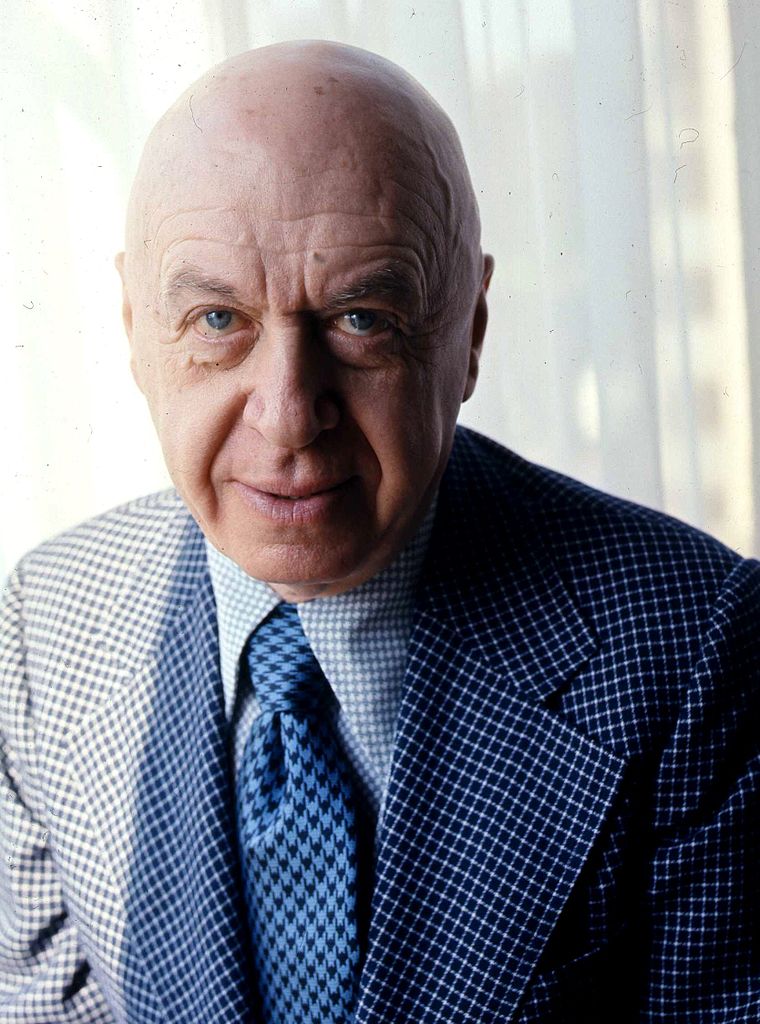

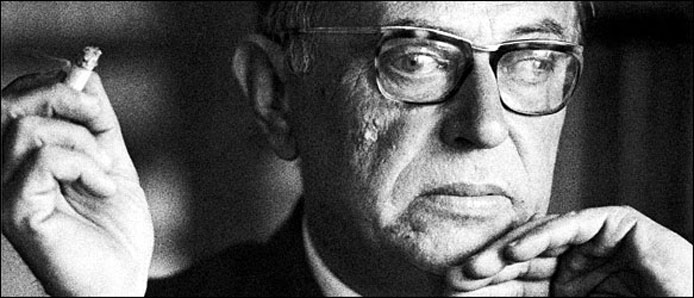

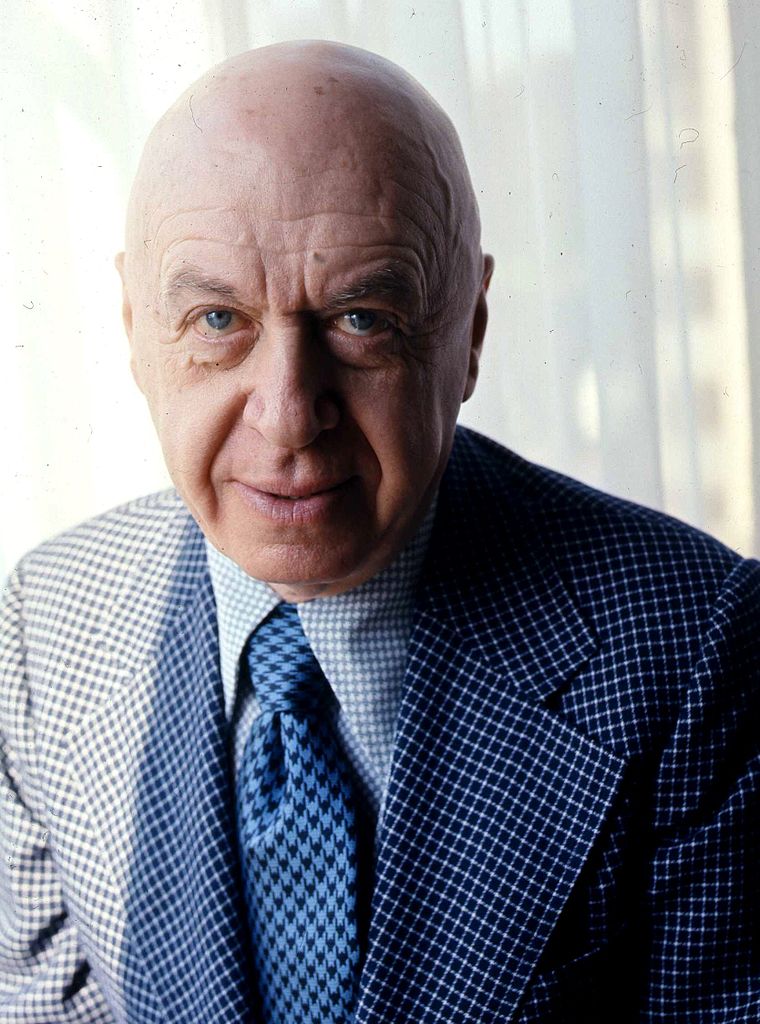

Otto Preminger’s body of work is wildly uneven but at his best he was a master of cinematic style — something the critics and directors of the French New Wave celebrated tirelessly but which has been largely forgotten in our time.

Preminger had an instinctive gift for creating arresting cinematic spaces, exploring them with a moving camera and choreographing movement through them. His method with these things was showier than John Ford’s, subtler than Orson Welles’s, but can stand comparison with the craft of either of those more revered directors.

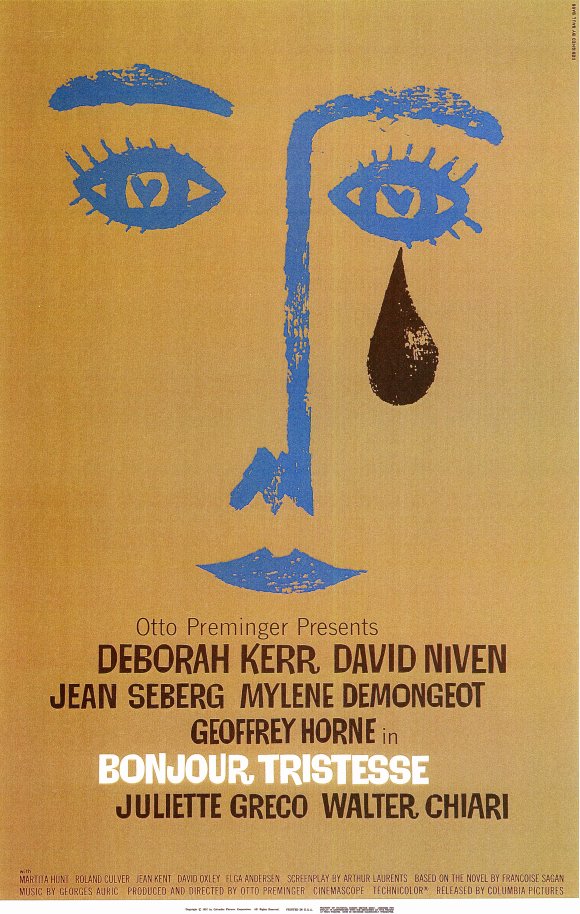

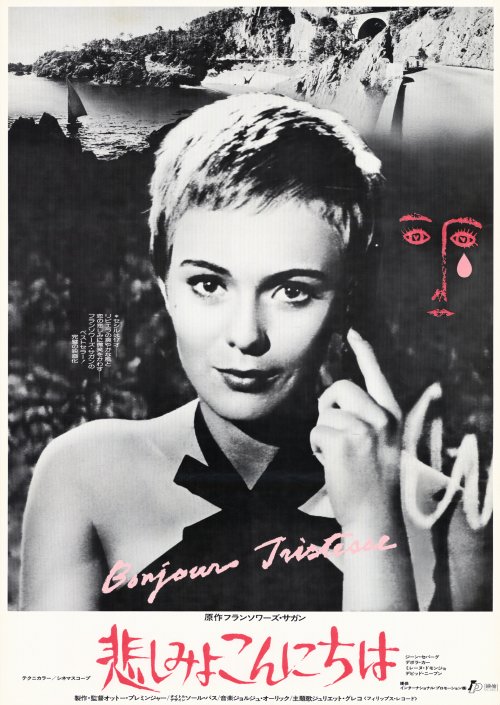

Like Ford, Preminger was a martinet on the set but, unlike Ford’s, his abusive ways didn’t always motivate his actors to give great performances. Still, when he cast a film well, he presided over some memorable ones, and Jean Seberg’s performance in Bonjour Tristesse is one of the most memorable of them all.

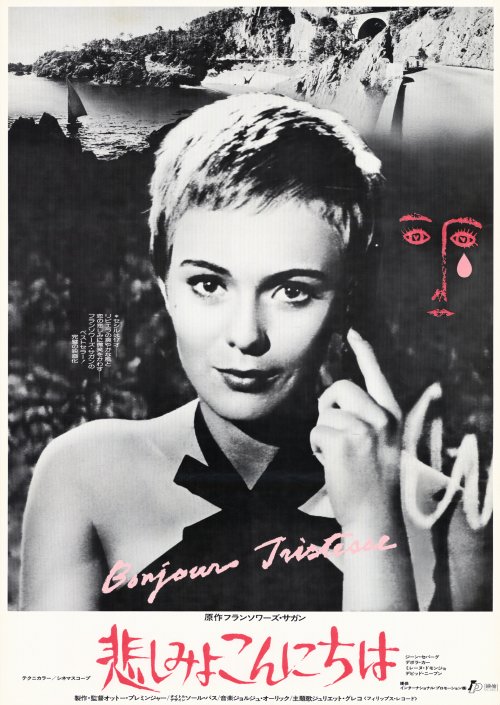

Preminger had plucked her from obscurity for the title role in his film Saint Joan, in which she was brilliant but for which she received scathing reviews. Casting her as the lead in Bonjour Tristesse was a kind of reparation by Preminger for this unaccountable public humiliation.

As in the earlier film, Seberg doesn’t exactly act — she just has her being in front of the camera and becomes fascinating, in a way many better trained actors never manage. Her delivery is sometimes flat, her line readings clumsy, but she seems to project her whole self onto the screen, and you can’t take your eyes off of her, even when she’s interacting with David Niven and Deborah Kerr, who both give brilliant but more traditionally crafted performances in the film.

It was part of Preminger’s genius to know that Seberg’s kind of performance can make for riveting cinema, even if it’s not what mainstream audiences are used to and expect. Godard, among others, however, knew what Preminger was up to, and carried it forward when he cast Seberg in his first film, Breathless, which he described as a documentary about Jean Seberg and Jean-Paul Belmondo making a movie. Their quirky onscreen personae never quite merge into the parts they are playing, and the tension of this is what makes Godard’s film so alive.

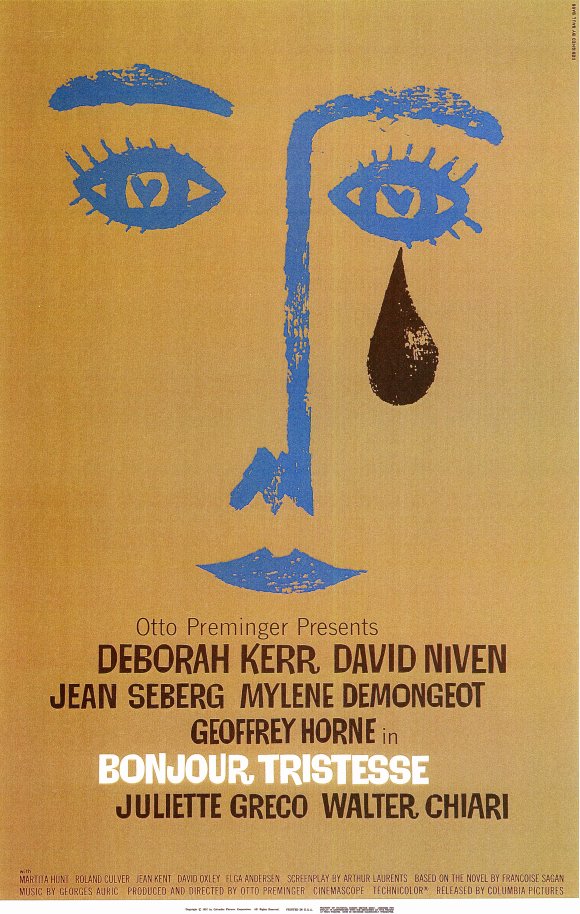

Seberg is the living heart of Bonjour Tristesse in the same way. Along with Preminger’s elegant shot-making, she transforms what might have been an overly precious coming-of-age melodrama into a cinematic marvel — working herself up to passages of emotional self-revelation that startle and devastate, climaxing in a final close-up that is surely one of the most powerful in screen history. Not that many people outside the offices of Cahiers du Cinéma appreciated her stealth genius at the time — the film tanked and Seberg again got dreadful reviews, which almost ended her career.

Twilight Time has just released a stunning Blu-ray edition of the film, and it’s a case where the higher resolution of the image reveals Preminger’s art more fully than the DVD edition, opening up spaces that you seem to fall into dreamily and in which Seberg’s magical screen presence blossoms and astonishes.

[The Twilight Time package contains, as usual, a superb booklet essay on the film by Julie Kirgo and an isolated track of the elegant and evocative score by Georges Auric. Actually, the score shares the track with the effects track, mostly heard between the music cues but sometimes underneath them. The effects track is extensive, very built up, suggesting that Preminger used very little location sound in the final film and looped most or all of the dialogue. It would be interesting to know if that was part of the production plan, allowing Preminger more freedom to move his camera on the practical locations where virtually all of the film was shot, or if it was something he decided to do after the fact in order to give him more opportunity to work with Seberg on her line readings.]

Click on the images to enlarge.

![usa_meet-the-beatles[1]](http://www.mardecortesbaja.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/usa_meet-the-beatles1.jpg)