Click on the image to enlarge.

A JOHN SINGER SARGENT FOR TODAY

AN EXPLOITATION MOVIE POSTER FOR TODAY

SECRET VIDEO

THE WIZARD OF OZ

Poster for the 1902 stage musical, which had at least as much influence on the 1939 movie as the books they were based on.

Many of the musicals Arthur Freed helped create at MGM were derived from the theatrical world of his youth, which he delighted in magically summoning back to life. He would have been eight in 1902. He would have been ten in 1904, the year in which Meet Me In St. Louis is set.

Click on the image to enlarge.

THIS MODERN WORLD

AN LP COVER FOR TODAY

LINCOLN

Man, this looks bad.

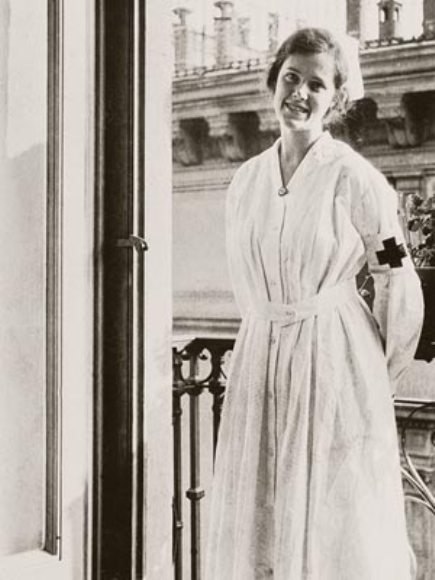

A MOVIE STILL FOR TODAY

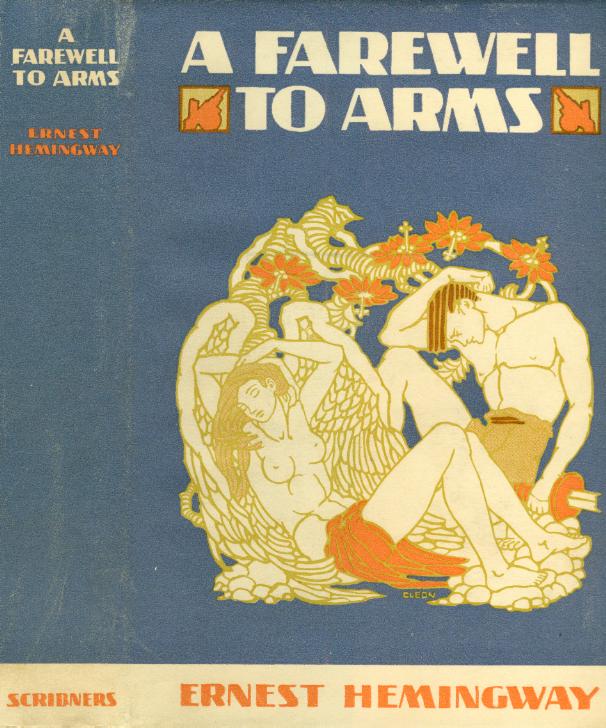

A FAREWELL TO ARMS

Ernest Hemingway’s occasional episodes of alcoholic bluster, part of his celebrity profile, give a misleading taint to his best work, in which macho swagger plays little or no role.

This is especially true of his two best novels, The Sun Also Rises and A Farewell To Arms. Both have boyish protagonists who are basically sweet and bewildered, scarred, as Hemingway himself was, by the psychic and physical wounds of war.

[Spoilers below — don’t read on if you haven’t read the novels in question.]

Jake Barnes in The Sun Also Rises has been rendered impotent by his war wound, and weeps at night over the impossibility of a physical relationship with the woman he loves.

Frederic Henry in A Farewell To Arms is recalled to life from his wounding by falling unexpectedly in love with a nurse working in the war zone. He is so stunned and overwhelmed by this love that war no longer makes sense to him, and he plots to find a way out of his obligations as a soldier.

A Farewell To Arms is as touching a portrait of first love as one can find in literature. The innocence and excitement and silliness of it are bluntly rendered, to the point that it’s almost embarrassing. Hemingway wrote this fictional version of his own wartime romance with a nurse some ten years after it occurred, and it’s hard to know what sort of distance from it he had acquired in those years.

Did it still seem as grave and profound as it must have at the time, or did Hemingway cast a colder eye on it when creating his scenes of an almost adolescent passion? It hardly matters — Frederic Henry’s youthful ardor rings true in either case. The end of it — Hemingway was dumped by his real-life nurse — must still have felt like a death to the man, ten years on, because he transformed the tragedy into a literal death, the death of Frederic Henry’s beloved.

I suppose you could say that imagining a literal death was more flattering to Hemingway’s masculine pride than the memory of getting dumped, but this doesn’t seem to be what motivated the recasting of events — the literal death of Frederic’s beloved and the child of his she was carrying (the child Hemingway might have had with his actual first love) feels more like an honest attempt to convey to a reader the cataclysm of the loss.

The loss of a first love, of any love that once seemed true and eternal, is always felt as a death, and Frederic’s blank desolation at the end of the novel is enormously affecting. Like Hemingway, Frederic witnessed the epic horror of war, but saw the loss of a woman he loved as somehow greater in the great scheme of things.

This is as far from macho posturing as it’s possible to get — it is the honestly felt wisdom of a man who was capable of loving a woman with the deepest part of himself, and saw the deepest part of himself ravaged, nearly obliterated, by losing her. Next to that, battlefield heroics, the soldier’s part, the sterile world of men without women, were simply nothing.

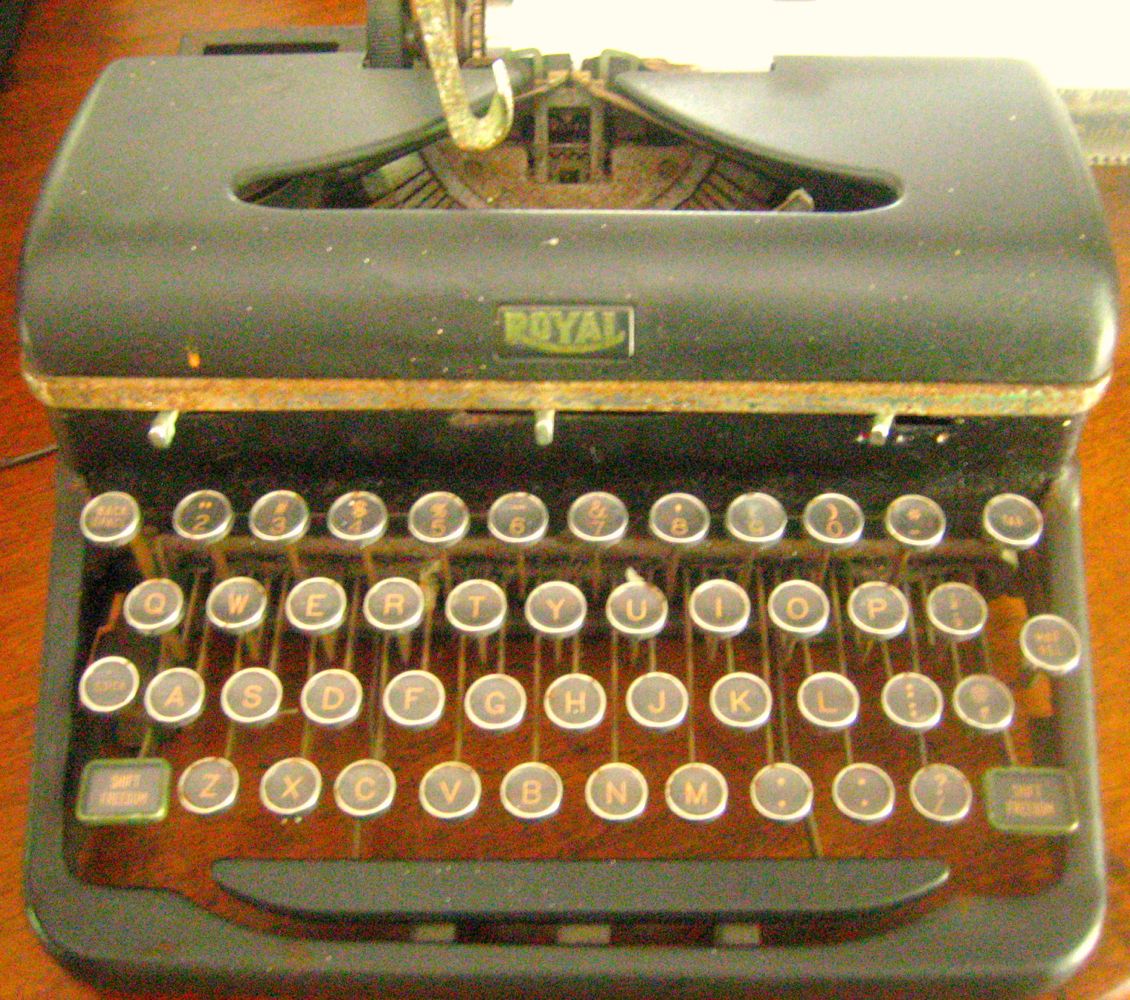

The Royal typewriter above is the one Hemingway used to write A Farewell To Arms.

A COMIC BOOK COVER PAINTING FOR TODAY

FOUR STRONG WINDS

A SILENT MOVIE LOBBY CARD FOR TODAY

ACROSS THE UNIVERSE

One of the most amazing of all music videos . . .