Click on the image to enlarge.

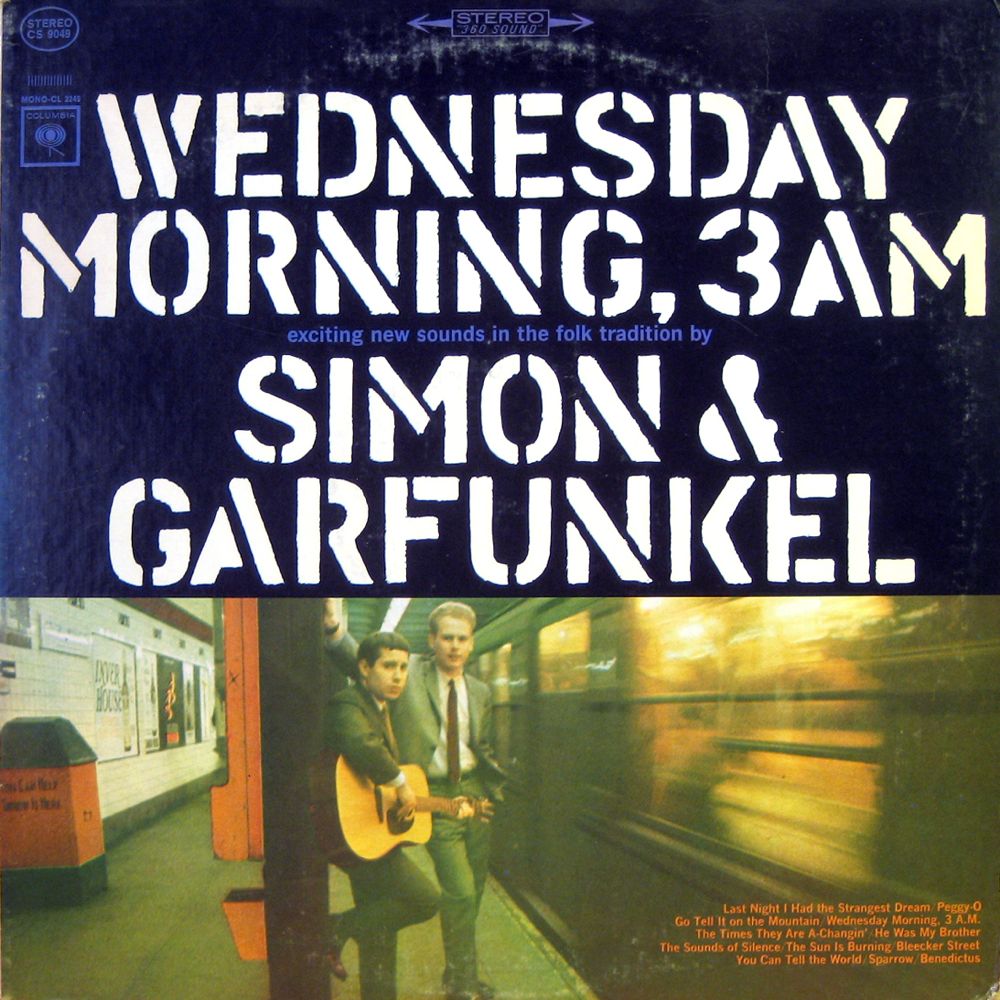

AN LP COVER FOR TODAY

ITINERARY

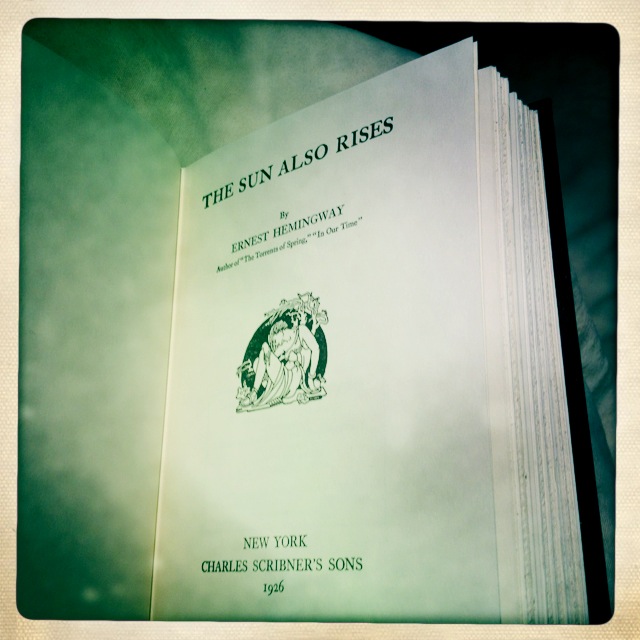

WHAT I’M READING NOW

TEARS

AFTER ISAAC

GATHERED AT THE RIVER

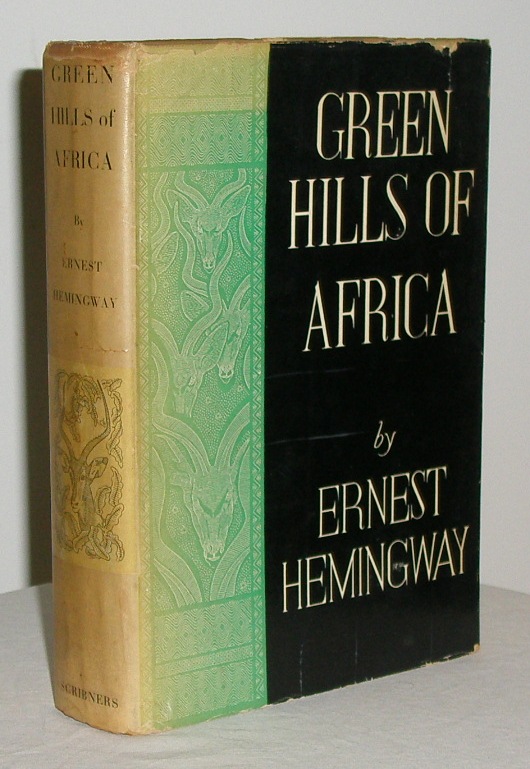

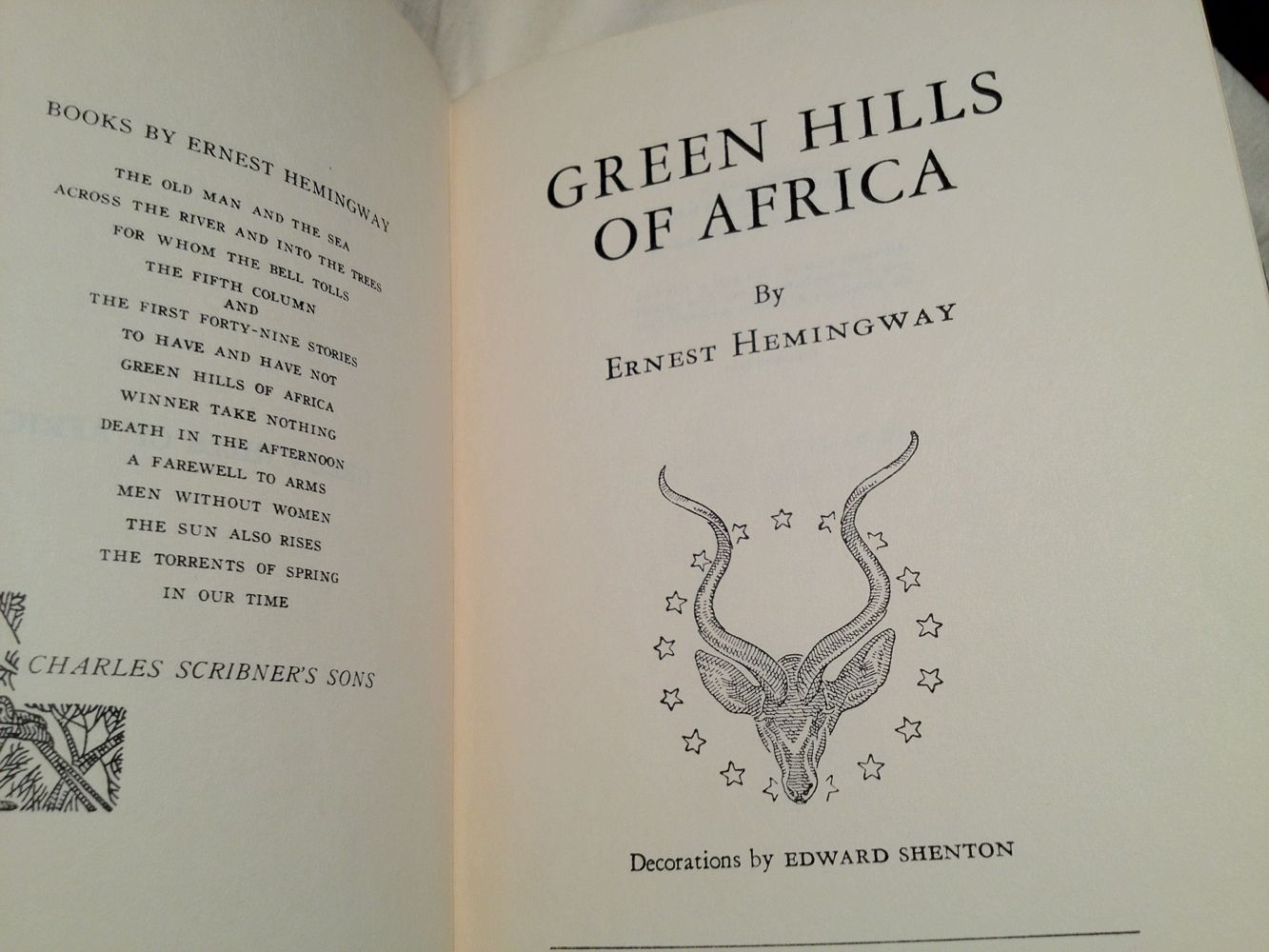

GREEN HILLS OF AFRICA

This book is an account of Hemingway’s first African safari, in 1933 — a more or less straightforward report of his adventures, but shaped with a novelist’s craft.

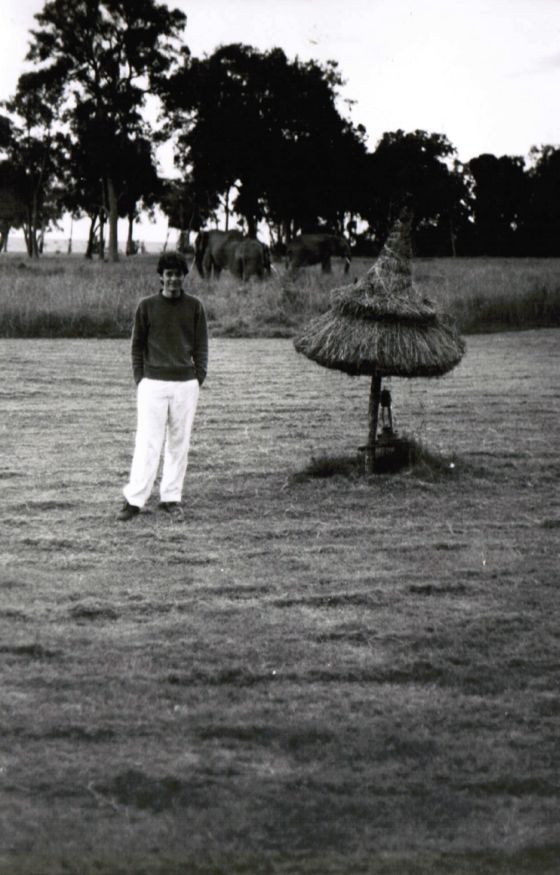

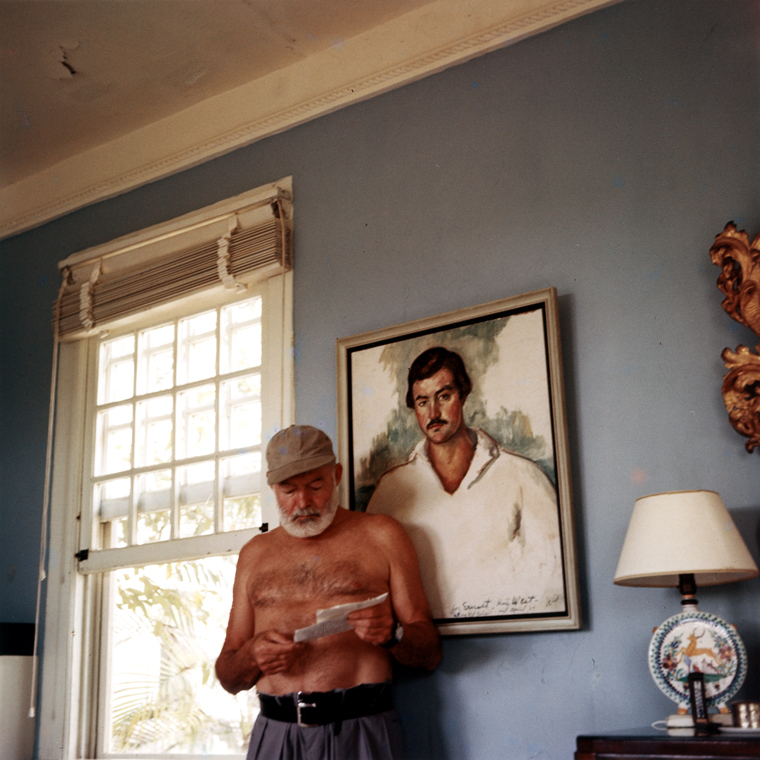

I read it for the first time in my late twenties, after my own first trip to Africa. My life had fallen apart and my sister Libba sent me a ticket to Kenya, where she was then living, and Africa put my life back together again. I suppose my sister knew that Africa would do this, but in any case it did.

[Photo by Libba Marrian]

I read the book to get Hemingway’s take on the place. I did not read it well back then. I was surprised by what seemed to be irrelevant pontificating about the state of modern literature, and by the pettiness Hemingway ascribed to his own character in certain episodes of the narrative. I found the book entirely fascinating but odd, vaguely disappointing. I somehow missed the shape of it, and the power.

The pontificating about literature amused me, late in life, and touched me. It was sort of like Babe Ruth calling a home-run shot, saying, “I’m going to beat this pitcher and knock one out of here.” Hemingway was promising the same, “the pitcher” in his case being his literary competitors, the home-run being the book he was writing. This seemed like a fine sporting gesture, and one that could be made only by a very fine writer who knows he’ll have more times at the plate if he strikes out in this one.

Green Hills Of Africa is not a dazzling shot out of the ballpark — more like an inside the park homer, solidly hit to the wall, between the fielders. Hemingway has to run like hell to beat the throw home and for long moments you’re sure he won’t make it, but he slides under the catcher’s tag at the last moment and scores.

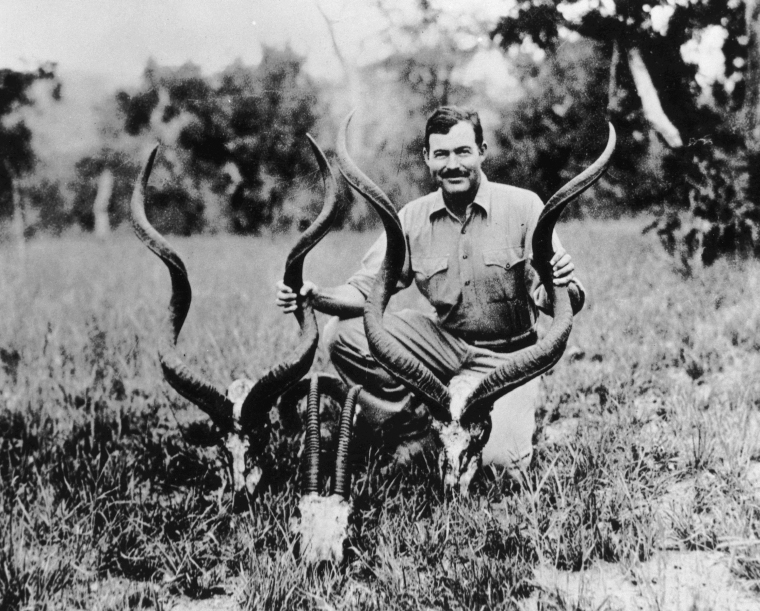

It takes some extraordinary writing to do this, and a long final brilliant section about a desperate but exhilarating kudu hunt, in which he hits the dirt in front of the plate, slides outside it but manages to get one hand on it as he passes it, scoring the run.

Reading the book the second time I was moved almost to tears by this section — entitled “Pursuit As Happiness”. In it, Hemingway evokes with startling clarity the country he was hunting through, the precise details of the hunt, as well as the almost supernatural joy he took in the endeavor, threatened constantly by his sickening fear that he would lose track of his prey, or shoot badly when he came up on it.

I’m not a hunter myself — I’ve never even fired a gun larger than a BB rifle — but the pursuit Hemingway writes of here can stand for every kind of pursuit, the pursuit of excellence in your work, the pursuit of a woman, the pursuit of any moment in life lived to its fullest.

As is usually the case with Hemingway, the end of the pursuit is never quite what the hunter imagined it would be, never as satisfying, but it’s something more, too, something beyond what he could have imagined — a memory of exaltation that exists forever, that can be put into words so others can share it. The exaltation is spiritual — it comes from a sense of having been if only briefly in touch with something eternal, bigger than oneself, something that will carry on in all its glory and power after one is gone . . . something that. once experienced, confers a kind of immortality.