Click on the image to enlarge.

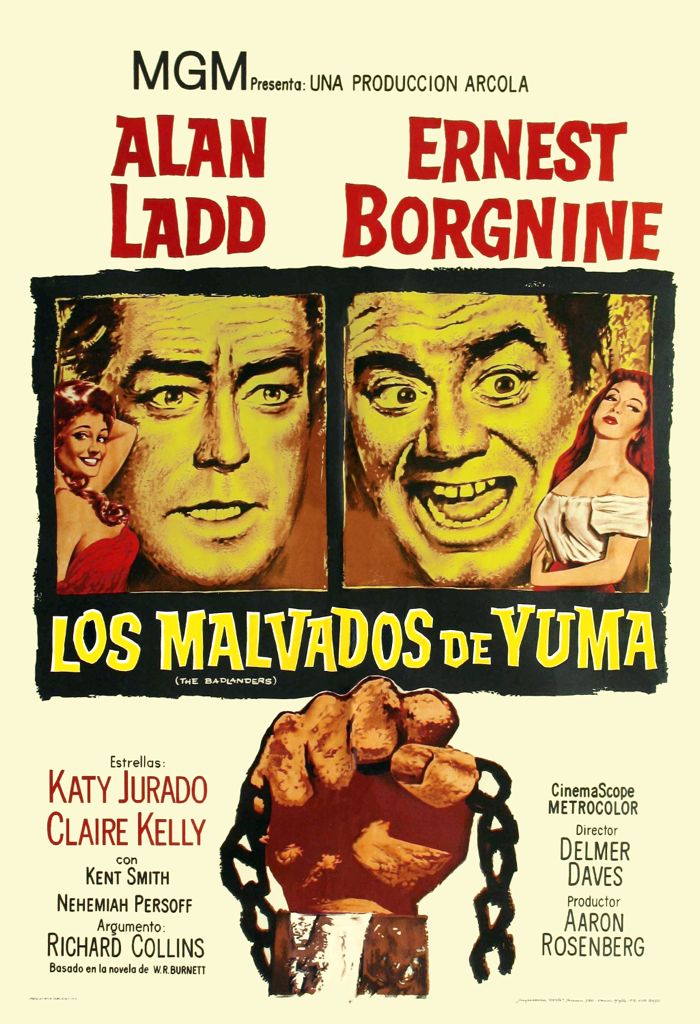

A WESTERN MOVIE POSTER FOR TODAY

A SONG FOR TODAY (TONIGHT): WYOMING LULLABY

A live recording (by Corinne Chubb) of Wyoming Lullaby (© 2002 Fonvielle-White) performed by J. B. White, who wrote the music, with back-up by members of The Carney Cowboy Band.

If you’re having a hard time getting to sleep at night, this song should do the trick for you.

Image above © James Bama.

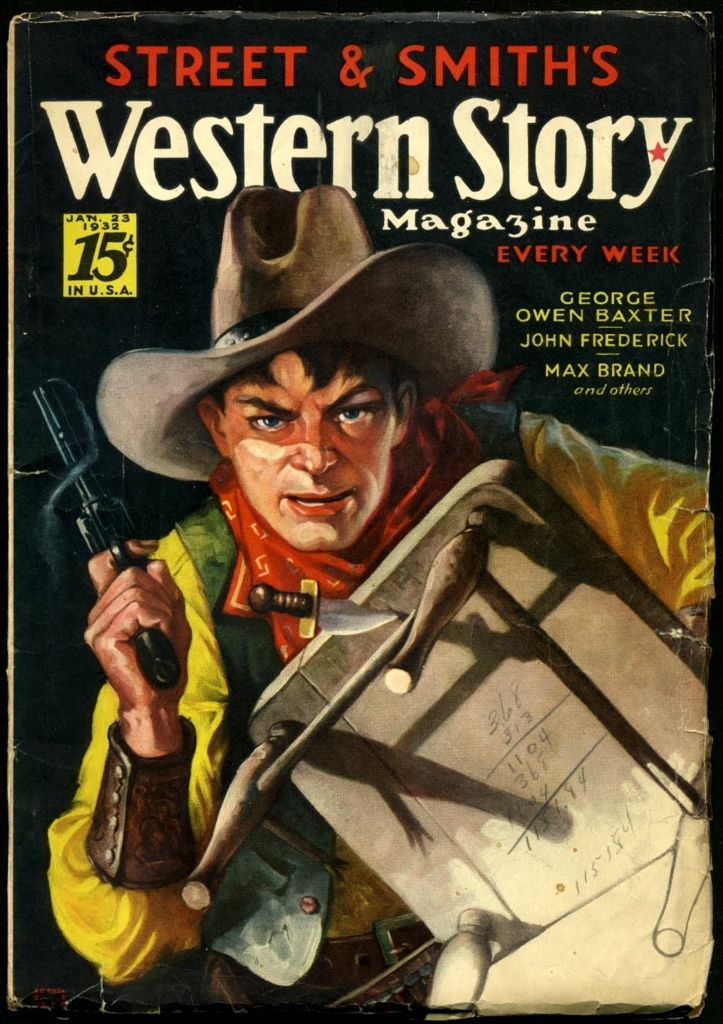

A JAMES MONTGOMERY FLAGG FOR TODAY

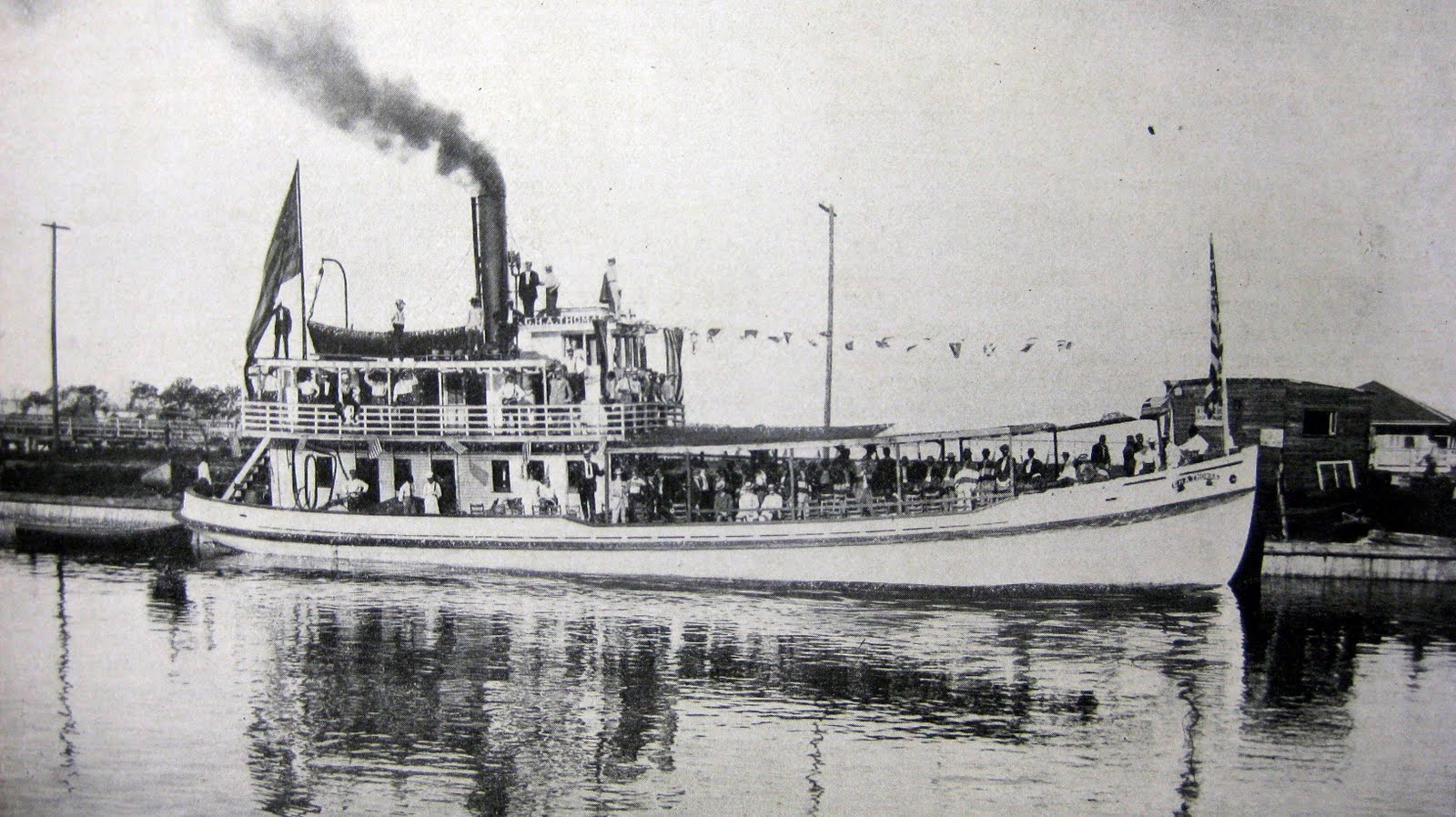

AN E. J. BELLOCQ FOR TODAY

Although known today for his remarkable portraits of prostitutes in the Storyville district of New Orleans early in the last century, work he did for his own pleasure, E. J. Bellocq was a professional photographer as well. Not much of his official work remains, and what does doesn’t seem extraordinary, though it’s certainly evocative.

This is a boat docked at the New Basin Canal in 1908, preparing to take folks on an excursion around Lake Pontchartrain.

Click on the image to enlarge.

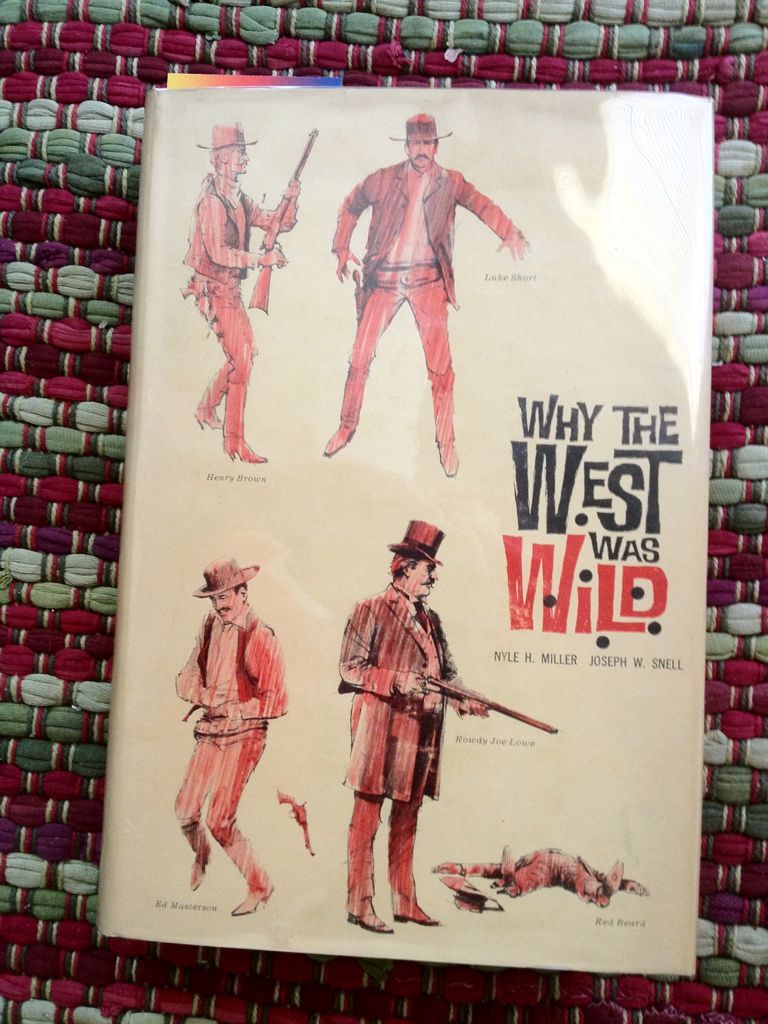

WHY THE WEST WAS WILD

This is the best book ever written on the Old West. I’m tempted to say the best book ever edited on the Old West, because it consists primarily of contemporary documents, mostly newspaper reports but also letters and court transcripts — but the truth is that the documents are so well-selected and the terse commentary is so trenchant and learned, that it feels more composed than compiled.

Almost everything written about the Old West has been fancied up and glamorized, even in the memoirs of people who helped make the history of the West. There has been an irresistible urge to feed the mythology that folks back east and later generations seemed to love and need so much.

Why the West Was Wild is a record of the way it really was — harder, darker and way more surreal than the myths have allowed. Somewhat narrowly focused, it’s organized as a series of biographies of notable figures from the cow town years in Kansas — the late 1860s to the late 1880s — but those were the years and the region in which much of the mythology of the West was born.

Although it has the form of an encyclopedia or biographical dictionary, it reads like a collection of riveting short stories about a place and time we only think we know.

It’s still in print, from the University of Oklahoma Press.

Click on the images above to enlarge.

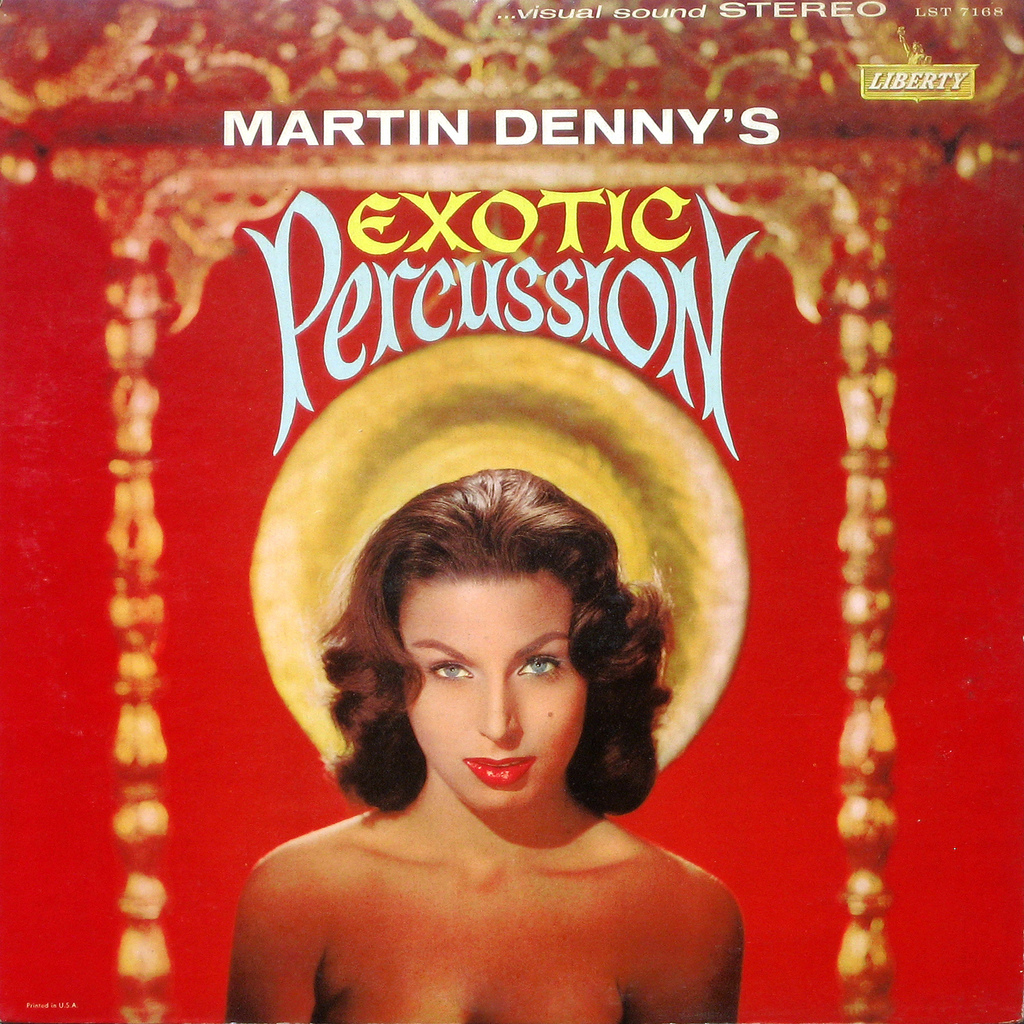

AN LP COVER FOR TODAY

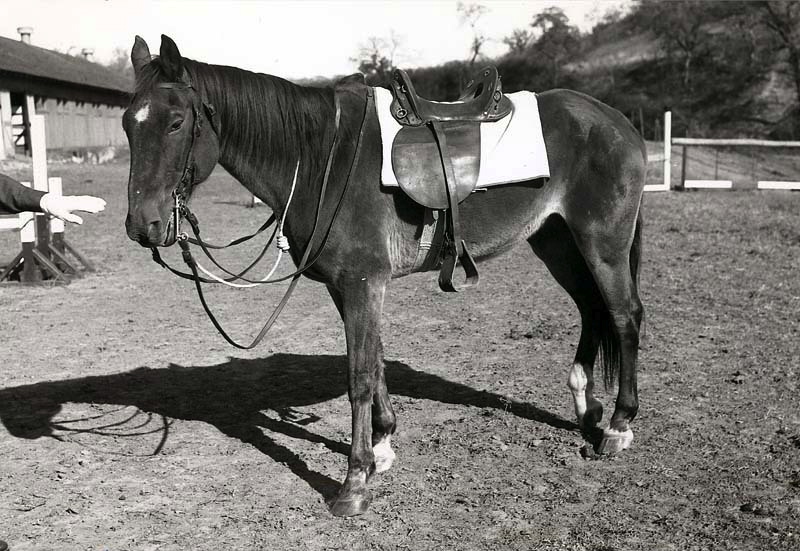

CHIEF

Chief was the last mount on the rolls of the U. S. Cavalry, officially eliminated as a branch of the U. S. Army in 1942. He spent his twilight years at Fort Riley, Kansas and died in 1968.

The McClellan saddle he’s wearing saw epic service, too. It was the standard-issue U. S. Cavalry saddle from shortly after the Civil War to the end of the arm’s existence. Hollywood bought up hundreds of surplus McClellans over the years, for use in Westerns featuring cavalry. In the 19th Century, the leather of the saddle was black, changed to brown in the 20th Century. The brown version is always seen in Hollywood films — a minor historical inaccuracy considering Hollywood’s scrupulousness about getting the style of the cavalry saddle right.

Click on the image to enlarge.

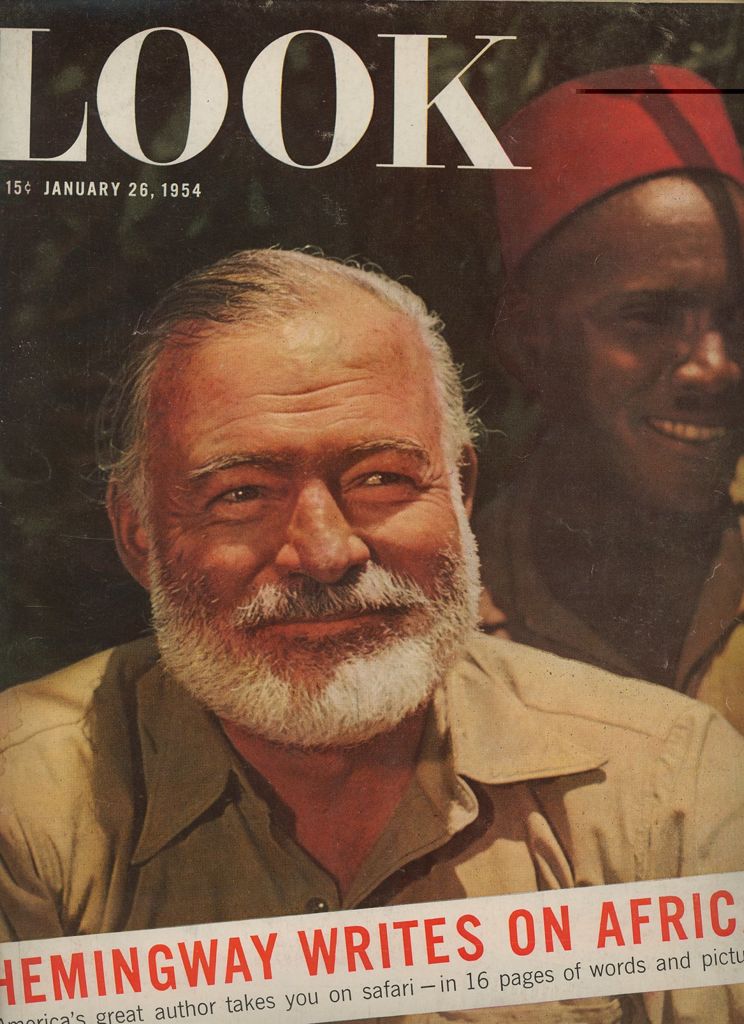

MORNING BEER

I nearly always drank beer for breakfast unless we were hunting lion. Beer before or at breakfast was a fine thing but it slowed you up, possibly a thousandth of a second. On the other hand it made things seem better sometimes when they were not too good and it was very good for you if you had stayed up too late and had gastric remorse.

— from Under Kilimanjaro

Click on the image to enlarge.

AN E. J. BELLOCQ FOR TODAY

A MARTIN KOENIG FOR TODAY

Nurse Transplanted, romance paperback cover, 1971.

The nurse’s face, which is what Koenig wants you to concentrate on, is sharply rendered. Everything else in the painting gets sketchier the farther it is from her face. This became a common technique when the style of story illustrations got looser in the Sixties and Seventies. It mirrored the increased use of shallow focus in movies, often achieved with telephoto lenses, as a stylistic device. It’s subtly done in Koenig’s image, and very effective — you notice the face before you notice the technique — which was not always the case with telephoto shots in movies of the same era.

Click on the image to enlarge.

AN LP COVER FOR TODAY

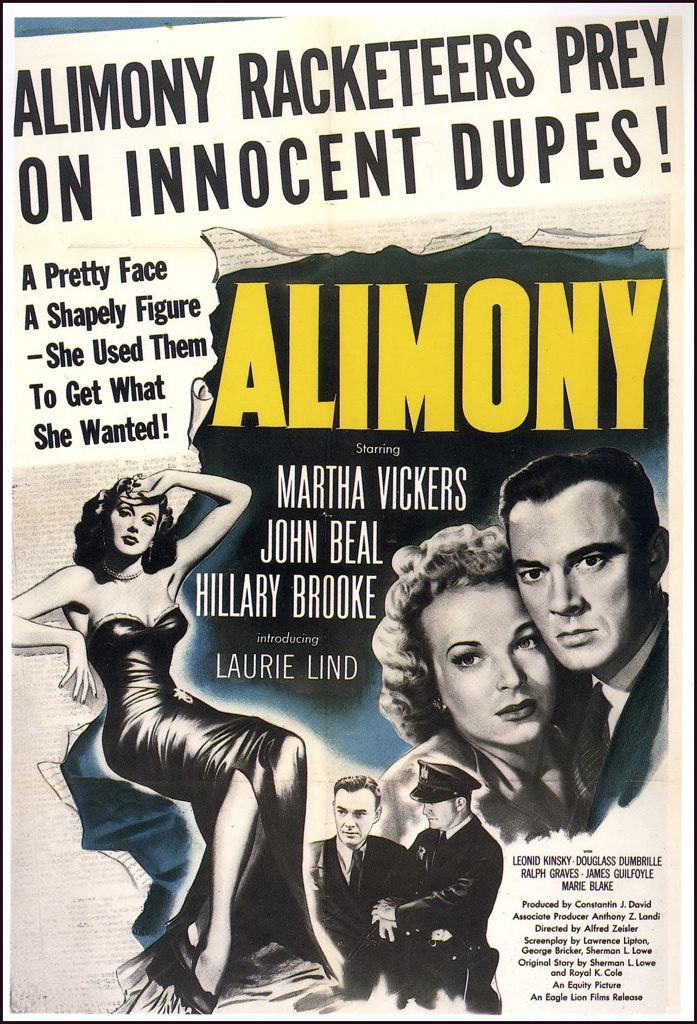

A MOVIE POSTER FOR TODAY

NOTE FROM THE SOUTHERN WILD

My nephew Harry Rossi, filmmaker, has this to say about Beasts Of the Southern Wild:

Click on the red text above to see Harry’s piece, click on the image to enlarge.

AN AMY CREHORE FOR TODAY

Amy Crehore has created a lot of magical images, but this one, Blue Mirror, is one of the loveliest. You can see it and other images from various sources at her blog Little Hokum Rag.

Image © 2012 Amy Crehore — click on it to enlarge.