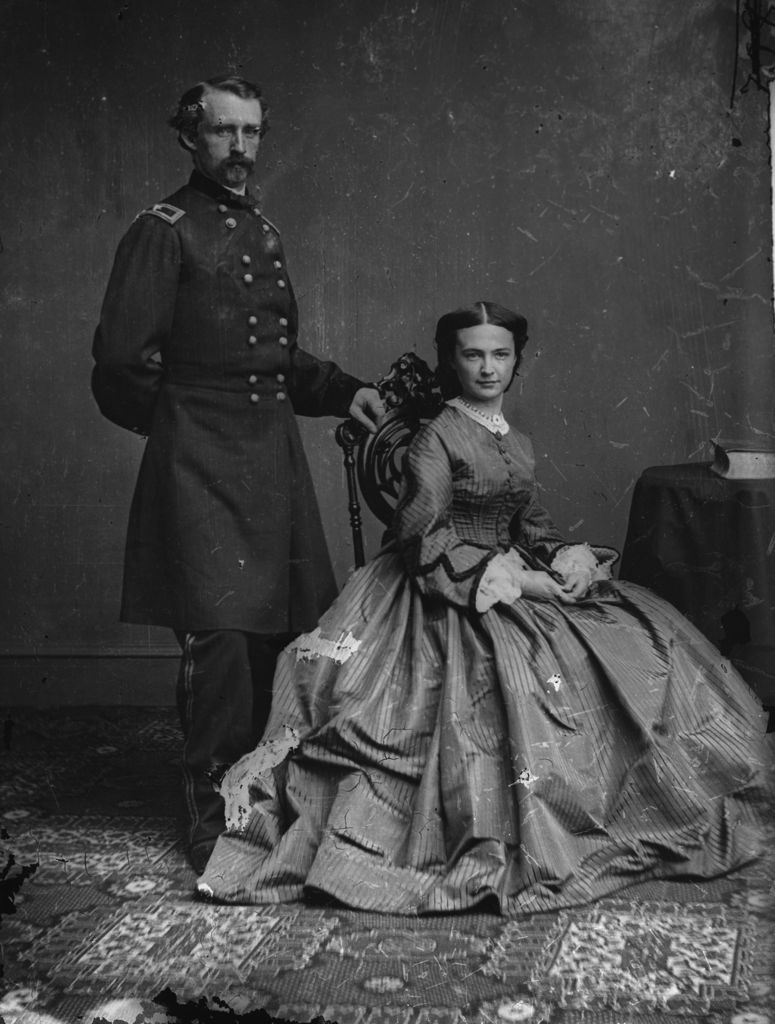

GEORGE AND LIBBY CUSTER

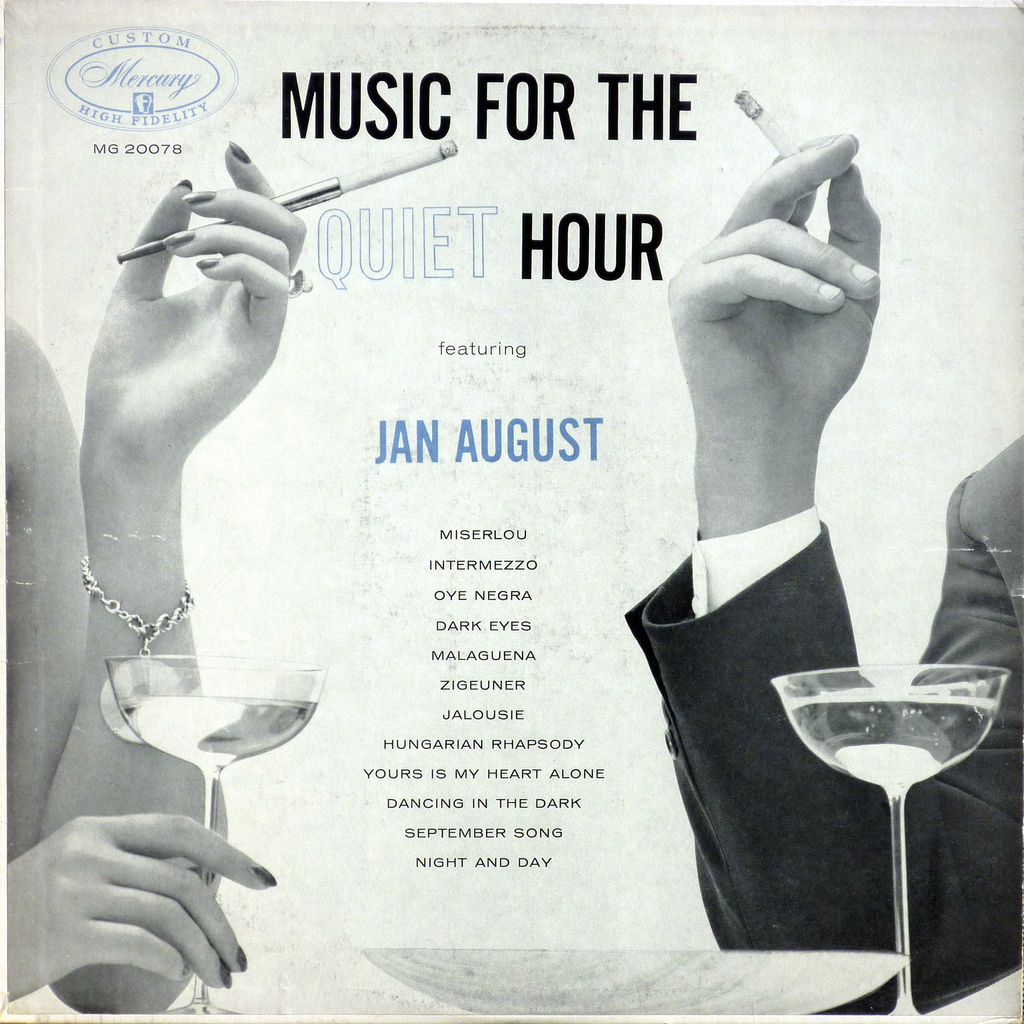

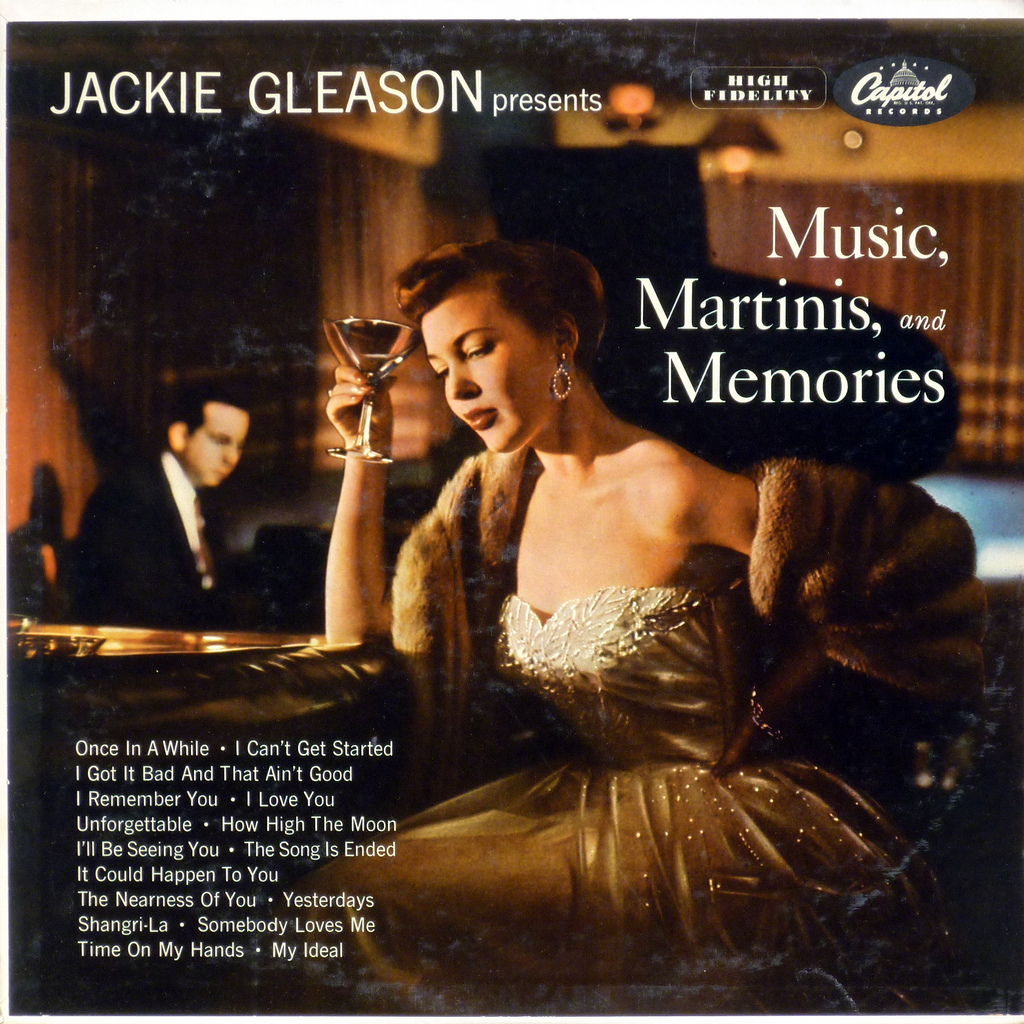

AN LP COVER FOR TODAY

SOMETIMES IT’S NICE

AN LP COVER FOR TODAY

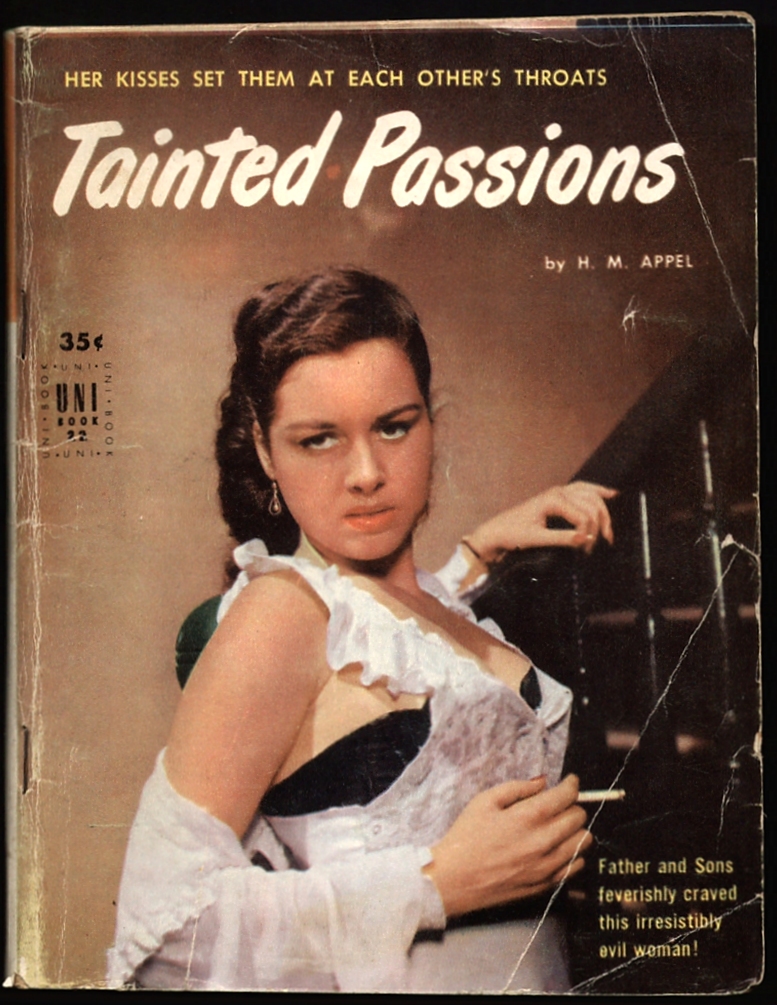

AN E. J. BELLOCQ FOR TODAY

At first glance, this woman, a prostitute in the Storyville district of New Orleans around 1912, seems to have a look of insouciant amusement, of ironic detachment, on her face. Study it a bit longer and you see the sadness, the despair, in her demeanor. The insouciant attitude was probably a professional mask — good enough for a drunken client in a room lit by gaslight or lamplight — but starting to crumble a bit in the light of day.

I think it’s one of the most remarkable portraits in the history of photography.

This woman might have been walking along a street in New Orleans one day near where she worked and have seen an eleven year-old Louis Armstrong selling papers on a street corner.

Click on the image to enlarge.

A MOVIE POSTER FOR TODAY

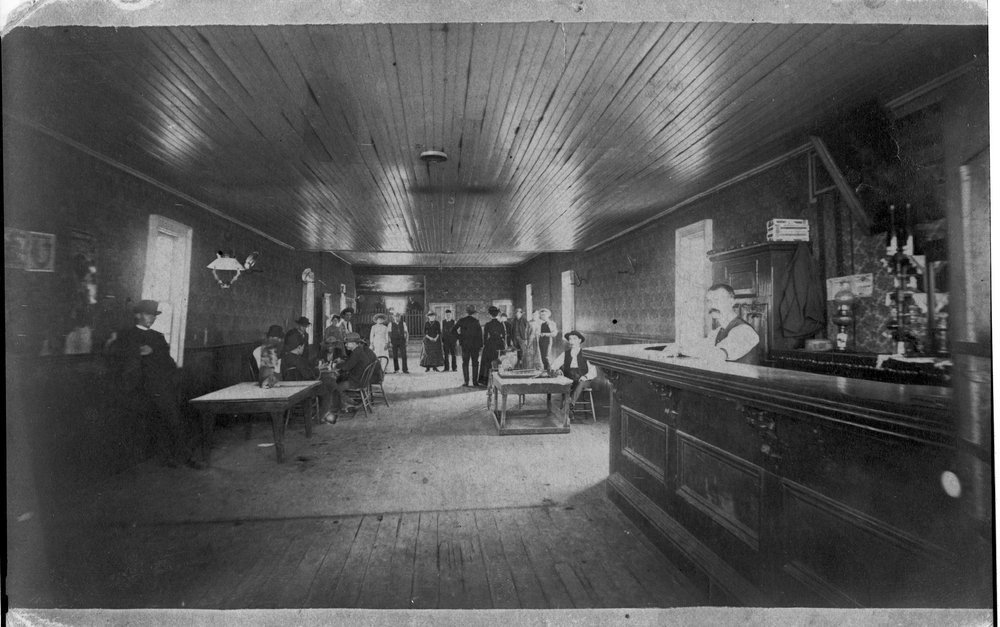

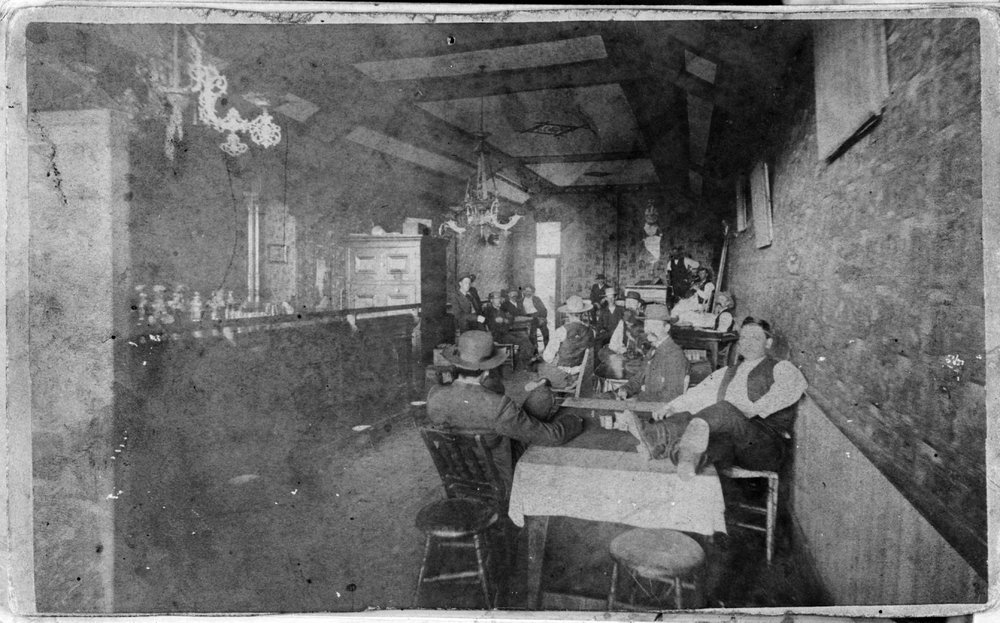

SALOONS AND DANCE HALLS

Saloons in the Old West were not the ornate Victorian establishments often depicted in Hollywood movies. That’s The Long Branch above, a famous saloon in Dodge City, Kansas during the years of the great cattle drives. A bar might have, like The Long Branch, an ornate carved bar with a big mirror and perhaps a painting of a naked woman behind it, but otherwise it was just a kind of shed with some tables and chairs in it. Often it was no more than a tent with bar furnishings set up inside.

Bars in the Old West sometimes offered music and dancing but almost never had stages for entertainers to perform on. Dance halls were very similar, only with more floor space for the dancing, and they also often occupied tents. Below is the Varieties dance hall in Dodge City:

Dance hall girls were not tricked out ornately either, like the saloon entertainers in Hollywood Westerns, and they didn’t perform as solo dancers or in chorus lines. They danced with the men in the hall, usually while negotiating other services to be performed back where they lived, in boarding houses or tents in a separate part of town, to which prostitution was relegated.

Above is Squirrel Tooth Alice, a famous dance hall girl in Dodge City during the cow town years, in a formal portrait probably used for advertising purposes. She had a gap between her two front teeth and liked to keep prairie dogs as pets — thus her moniker. The Alice I can’t explain — her real name was Libby Thompson.

For the most part, prostitution was not legal in the Old West but it was taxed in the form of “fines”, which was really just a system of licensing. Many towns received the bulk of their income from fines for prostitution — they literally couldn’t afford to run the ladies off.

Surprisingly, saloons and dance halls in the Old West offered a rather sophisticated variety of spirits, freighted in from back east and even from abroad. Fine Bourbons and French wines could be had in the bars of towns of almost any size — any place where a gambler or cowboy or drummer with some coin in his pockets might turn up. Ice was also freighted in so that the saloons could serve cold beer.

Men of the Old West might not have cared much what a bar looked like, but they wanted the finest liquor they could afford in their glasses.

Click on the images to enlarge.

NEWS OF THE SATURNI

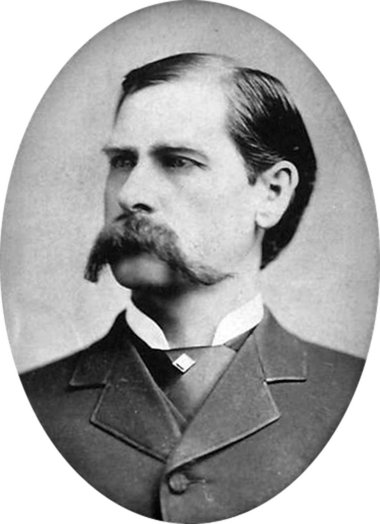

A KANSAS COW TOWN

Behind these rustic facades lurked a world of sin and temptation for cowboys just paid off after a long drive from Texas.

Longhorn cattle were so plentiful in south Texas that they weren’t worth a plug nickel locally. If you could get them up to the railheads in Kansas, where they could be shipped north and east, they were worth a small fortune. And so the trail driver, the classic cowboy, was born.

He was the guy who drove the longhorns north, took his wages and usually blew them in the notorious cow towns. His rowdy ways led also to the emergence of the legendary marshals who worked the cow towns, men like Wyatt Earp, who gained his reputation as a shootist, a gunslinger, wrangling high-spirited trail drivers in Kansas.

The era of the epic trail drives was brief, lasting less than 20 years — it ended when the railroads finally pushed their lines south into Texas cattle country — but it gave rise to an American mythology that is still with us today.

Click on the first two images to enlarge.

AN LP COVER FOR TODAY

SHAKESPEARE, NEW MEXICO

BELLE McKEEVER

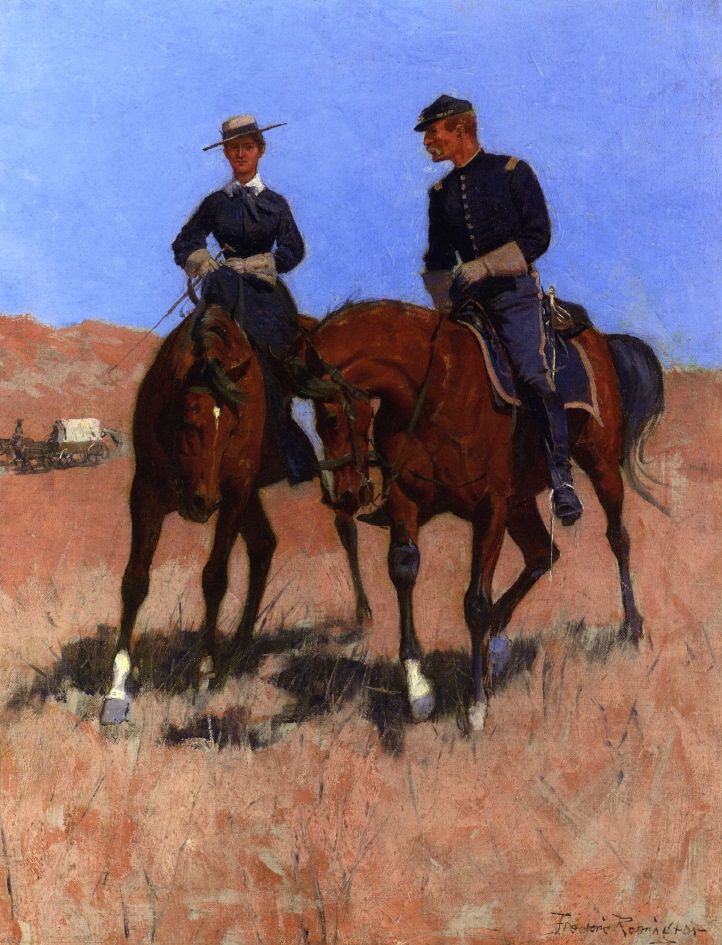

This painting by Frederic Remington was done for Harper’s Weekly in 1899, illustrating a story called “The Military Search For Belle McKeever”. The title of the painting is Belle McKeever and Lt. Edgar Wheelock.

I don’t know if the Harper’s story was a work of history or of historical fiction. Belle McKeever was a real person, abducted as a child by Apaches in Arizona in 1869. She and her brother were helping their father pan for gold in a creek on his claim when the father was killed and the girl taken. The boy escaped and alerted the authorities and the military did conduct a search for Belle but I can find no record that she was ever found — yet she appears in the painting as a grown woman, back in civilization.

She became famous because the troopers sent to look for her claimed to have discovered a rich though apparently abandoned gold mine in the mountains where they were searching. It came to be known as The Belle McKeever Mine, but no one was ever able to locate it again.

I’m guessing that F. McCarthy, the author of the story, supplied a fanciful and fictional happy ending to the story, involving a romance between Belle and a cavalry officer. The two horses getting set to nuzzle each other would tend to suggest some sort of budding affection between the riders.

It is, in any case, a wonderful and evocative painting. Note the McClellan saddle that the officer is riding — standard issue for the cavalry from soon after the Civil War to the dismantling of the arm in 1942.

Click on the image to enlarge.