Joan Didion wrote:

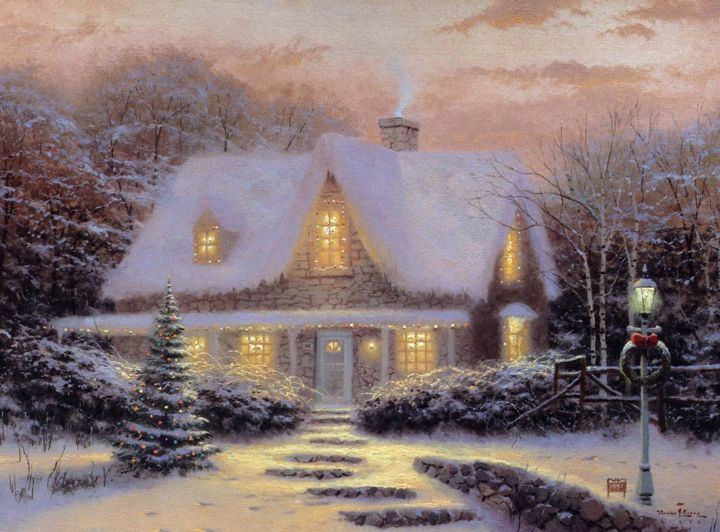

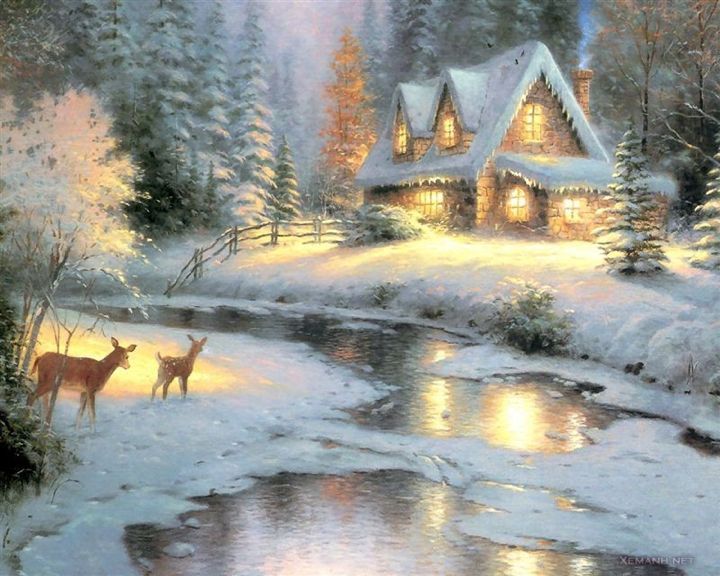

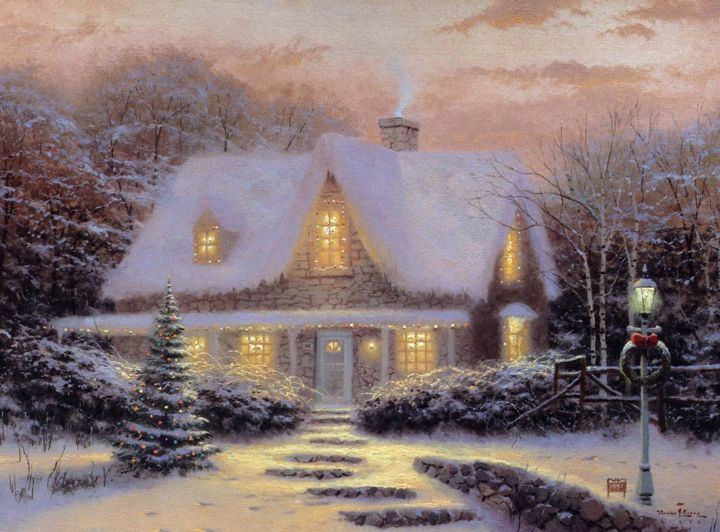

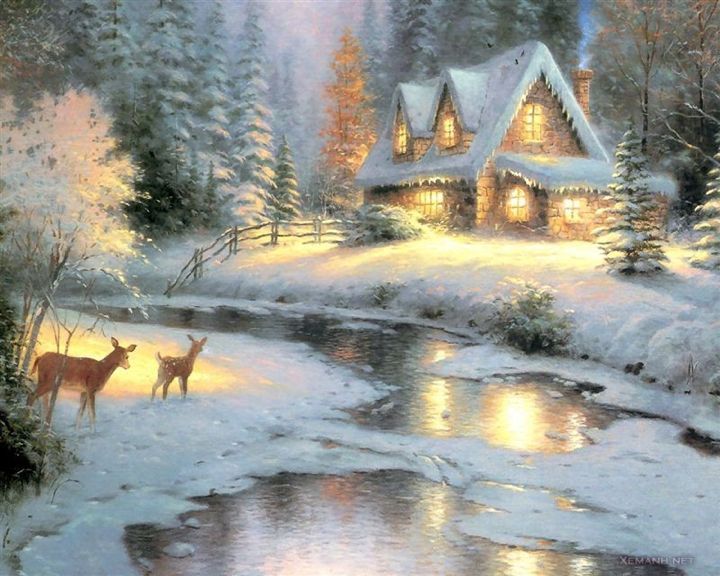

A Kinkade painting typically featured a cottage or a house of such insistent coziness as to seem actually sinister, suggestive of a trap designed to attract Hansel and Gretel. Every window was lit, to lurid effect, as if the interior of the structure might be on fire.

I myself don’t feel a sinister aura in Kinkade’s work — the home pictured above seems like a cheerful and inviting place — but Didion at least identifies a kind of power in his images.

It’s interesting, too, that no homey refuges like the ones he depicted were accessible to Kinkade in real life. He suffered from depression, over money, over the reception of his work by critics and over a painful divorce. He struggled with alcohol addiction, had had a relapse just before he died, and the cause of his death was an accidental overdose of anti-anxiety medication and drink.

His images of well-lit, inviting homes are usually pictured from the outside, often with paths through the winter snow leading towards the warmth inside. He saw himself apparently as forever stalled on the path, like the deer in the image above, on the outside, dreaming of a comfort that would always be just beyond his reach.

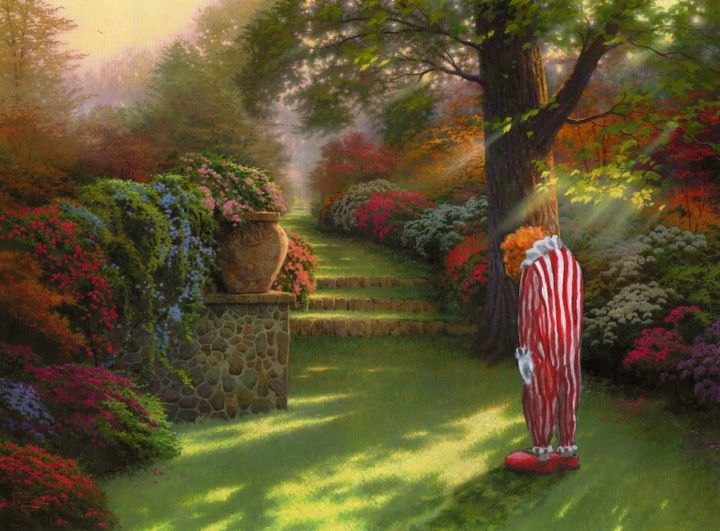

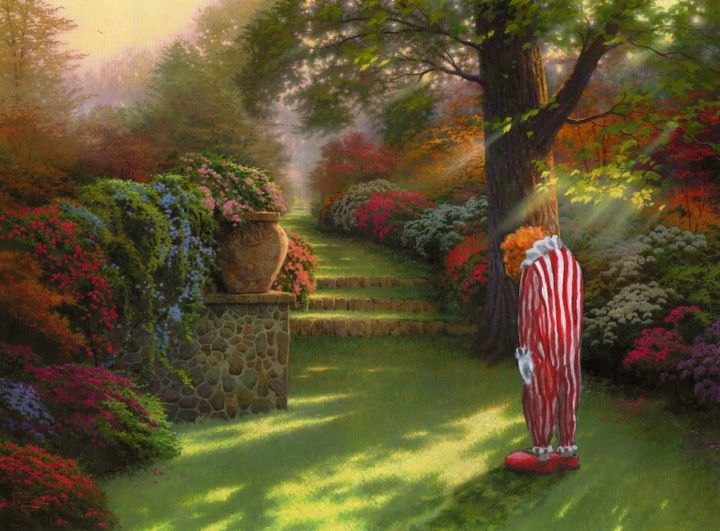

Kinkade rarely created explicitly surreal images, but look at this one:

It’s not terribly compelling as a painting but it may well represent a deeply-felt self-portrait. It’s called Pathway To Paradise — a pathway the artist, in the person of a sad clown, feels he will never walk, is perhaps not worthy to walk.

[You can read some earlier thoughts on Kinkade, with interesting comments, here — Light.]