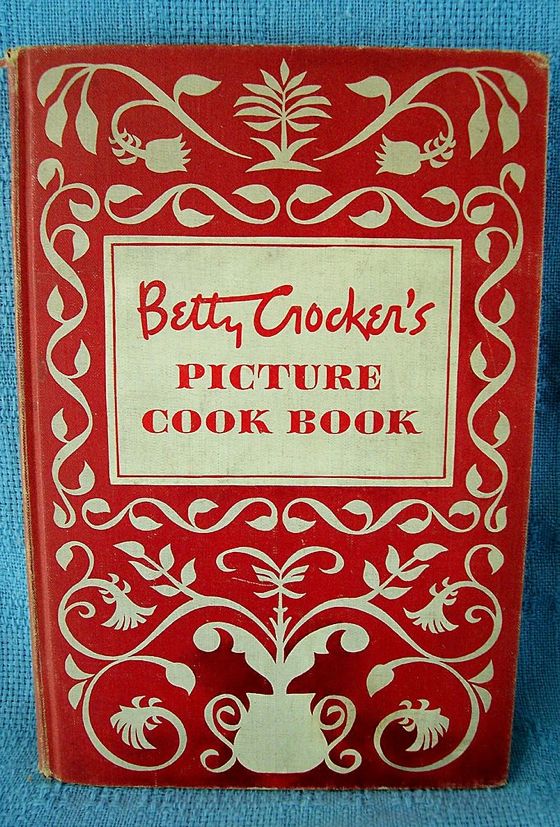

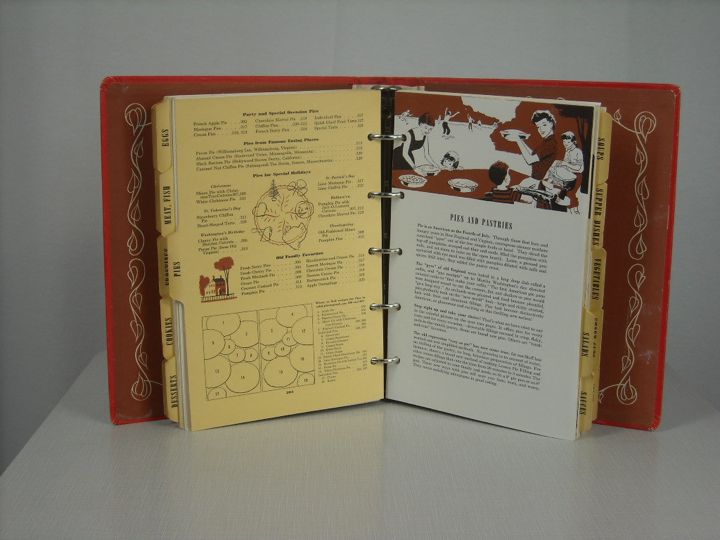

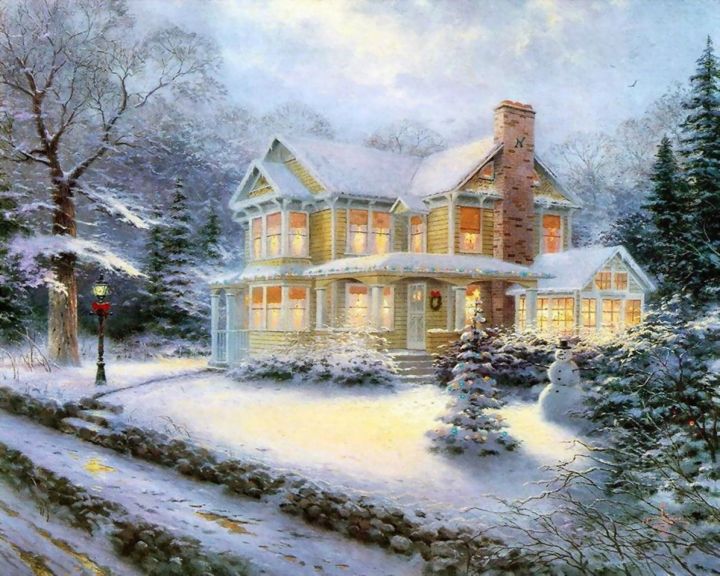

You would have been hard pressed in the 1950s to find a middle-class American home that didn’t possess a copy of this book — it sold even more copies than The Joy Of Cooking. Its recipes were illustrated with hundreds of step-by-step photos, and decorated with cheerful drawings of modern living.

Betty Crocker was a fictional person, the face of General Mills, a flour company, so her cookbook was heavily weighted towards baked goods, especially desserts. It emphasized brightly colored confections, compensation, it has been suggested, for the diminished taste of foodstuffs designed to be prepared quickly, often from mixes.

First published in 1950, the book had a spiral notebook design, so pages could be removed for easier perusal while preparing dishes. Like The Joy Of Cooking, Betty and her cookbook served in the place of mothers and grandmothers for women who had moved to isolated suburbs after WWII, cut off from their traditional kitchen mentors.

Its emphasis on convenience helped free women from time in the kitchen so that they could serve meals yet still join in the nightly gathering around the new American hearth — the television set.

Popular around the same time were table-top appliances that allowed women to prepare hot snacks or meals in the living room within sight of the television set. Swanson’s TV Brand Frozen Dinners, appearing first in 1953, took this idea to its logical extreme. The frozen dinners came in brightly colored packages which depicted the food inside the frame of a television screen. Collapsible table-trays, for eating such fare in front of the television, became standard fixtures of the American home in this era.