This is a most unusual book — one that could only have been created in the Internet age.

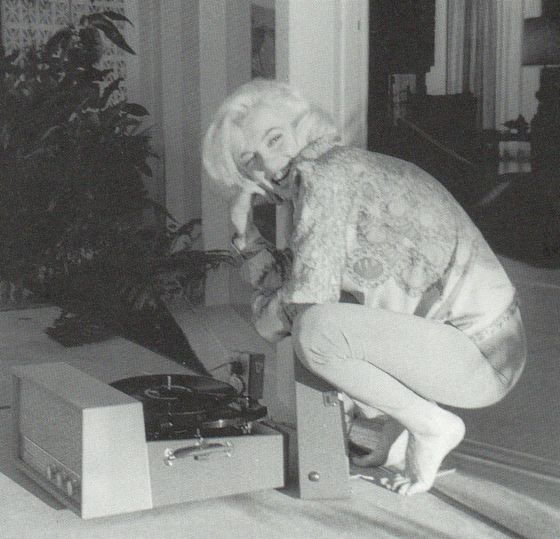

In 2003, a group of contributors to an online discussion group about Marilyn Monroe formed a splinter group devoted solely to a discussion about the details of her death — The DD (or Death Discussion) Group. The core of the group was made up of non-experts on most of the issues involved, though a couple of them had professional credentials in related fields and some of them spoke to people directly involved in incidents surrounding Monroe's death. All the members of this core group were fair-minded, intelligent and articulate individuals.

Basically what they decided to do was examine the available record (suspiciously incomplete) without fixed preconceptions, with a civil regard for all opinions, and then apply logic, basic common sense, to the myriad of contradictory, outrageous and patently false things that have been reported and written about Monroe's death.

They functioned in a way like an ideal jury, careful to distinguish between evidence that seemed reliable, evidence that derived from biased or unreliable witnesses, and sensible conclusions that could be drawn from the totality of the evidence. They reached consensus on a number of key issues, though there were always dissenters, were split on other key issues, and offered no final conclusions, of the sort that might be be considered “beyond a reasonable doubt” in a court of law.

What David Marshall, the founder and moderator of the group, has done in this book is to provide a lengthy record of the “jury deliberations” — rational and respectful exchanges that at the very least make clear what is known, what is not known and what might be intelligently concluded. Unless some of the missing evidence is brought to light, this will remain the final word on the death of Marilyn Monroe and the mystery that still surrounds it.

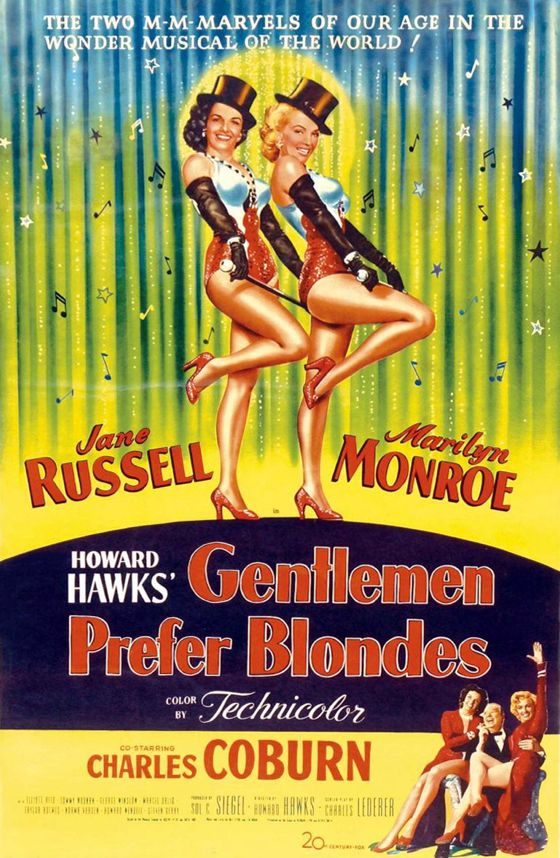

For the record, they offer convincing arguments that Monroe's death was set in motion, during the afternoon preceding the night she died, by a visit (or some other communication) from Robert Kennedy telling Monroe that she had to break off all relations with him and her brother, the President Of the United States, due to salacious rumors about those relations beginning to surface openly in the press. The Kennedys had earlier made a similar break from Frank Sinatra, a friend and supporter, due to rumors about his involvement with organized crime. The group concludes that Monroe had at least one sexual encounter with JFK, which initiated the rumors. but in all likelihood none with Bobby. She was, however, a friend and confidante of both, at least in her own mind, and emotionally devastated when she learned they wanted to cut her out of their lives. (Sinatra's reaction to being dumped was similarly intense, though his devastation took the form of violent rage and an enduring bitterness.)

The group members offer convincing arguments that Monroe was not murdered (by the Kennedys or anybody else) — that she died from an overdose of barbiturates, administered either accidentally by one or both of her primary physicians, by her housekeeper and minder, or by herself . . . or deliberately by herself, in a genuine suicide attempt or in the hope and expectation of being rescued, which had become one way she tried to reach out for help and attract sympathy.

That's it — two distinct probable causes of death, neither of them terribly sensational, except for the role of the Kennedys in setting off the emotional turmoil that led to the tragedy, and in organizing a cover-up about that role which has left significant gaps in the record of what actually happened, thus rendering Monroe's death perpetually open to wild and usually irresponsible speculation.

The crucial gap in the record involves the list of her phone calls on the day she died, which was confiscated from the phone company within hours of her death being reported to the police and never seen again — something that would have required intervention from the highest levels of the local or national government. It is extremely unlikely that local officials would have undertaken such an unusual, and illegal, intervention without direction from federal authorities in Washington, and then only to protect figures of unique power and prominence. It's unimaginable that Chief William Parker, the redoubtable and notoriously incorruptible head of the LAPD, would have ordered such an intervention just to protect Monroe's doctors, for example, or any of her Hollywood associates — he would have had to be convinced that issues of national security were involved.

The unanswered questions are frustrating, but this book gets you as close to the truth as it's now possible to get.