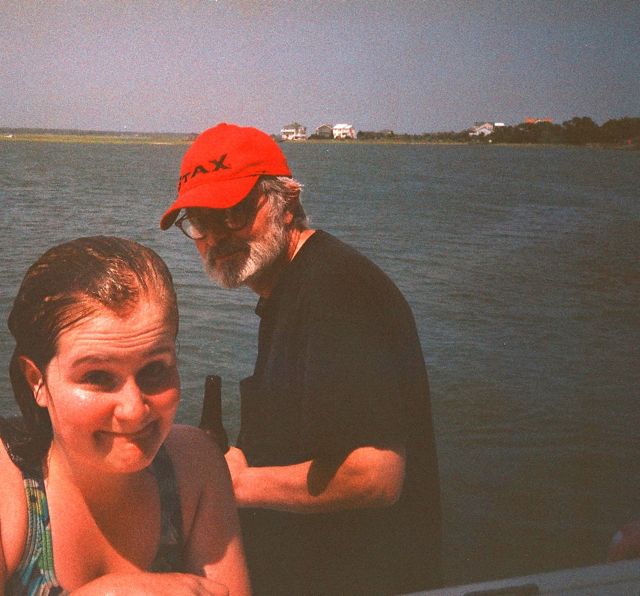

Wheeling Dad out for his last look at the ocean. Right up until the end he loved having his picture taken, and always put on his best face for the camera. He may not have known who or where he was, but he felt that the camera was his friend.

Wheeling Dad out for his last look at the ocean. Right up until the end he loved having his picture taken, and always put on his best face for the camera. He may not have known who or where he was, but he felt that the camera was his friend.

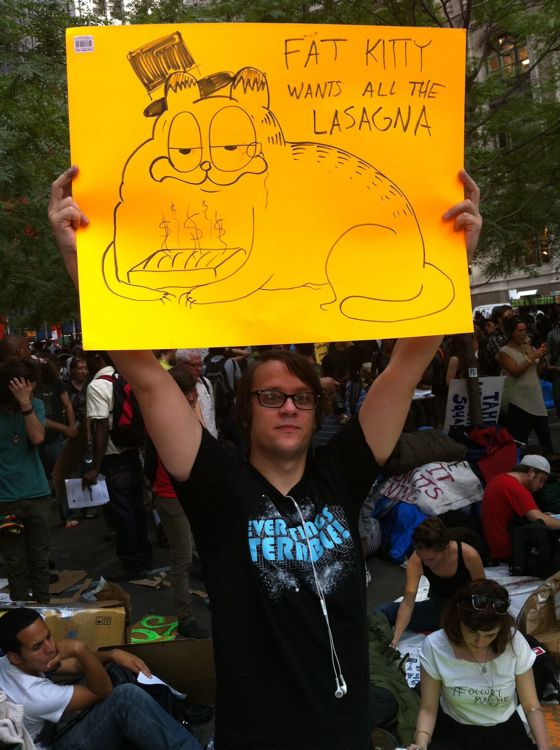

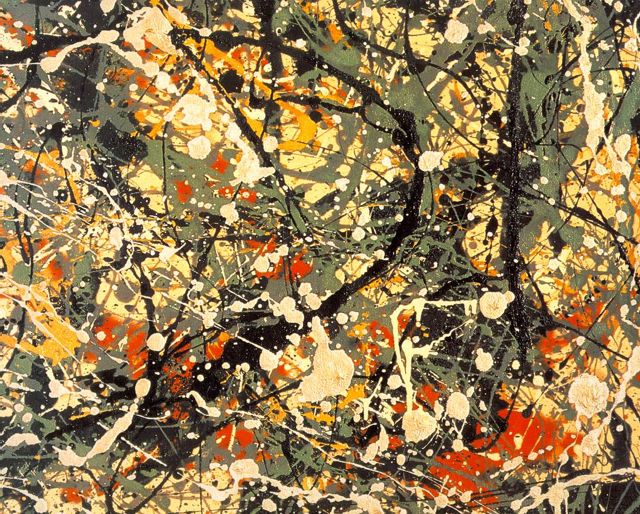

. . . takes his art down to Wall Street.

. . . with my niece Nora.

Le Bal de l'Opéra,

1886. I find this image totally ravishing — for its complex

progression of spaces, its photo-authoritative documentary quality and

its narrative suggestiveness. It draws you into itself on several

different levels all at once.

. . . with my sister Lee.

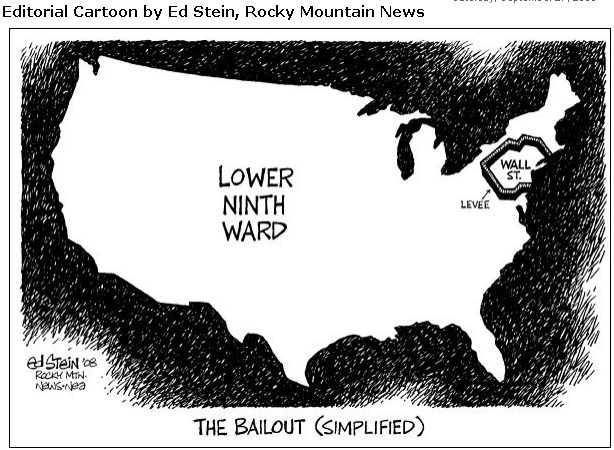

With thanks to Bill Bowman, who lives in New Orleans and knows how it goes . . .

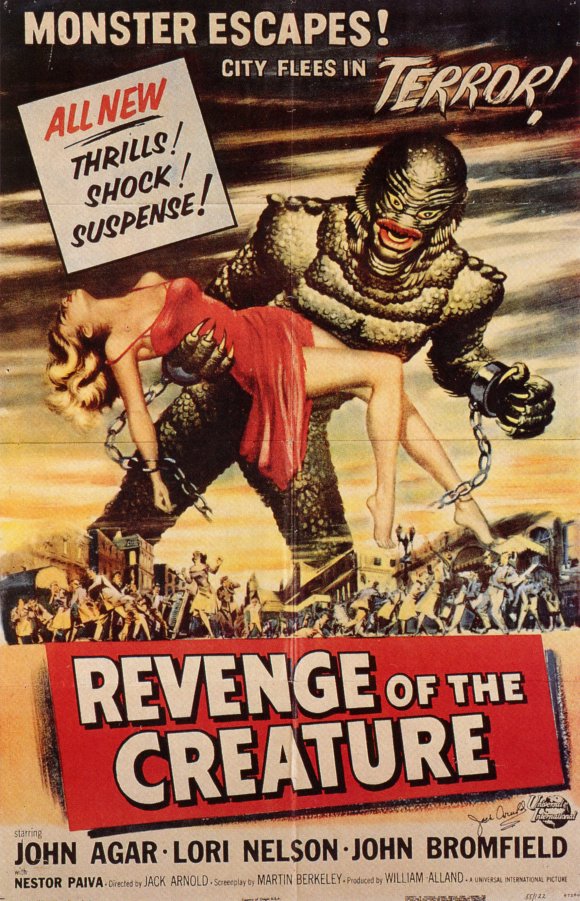

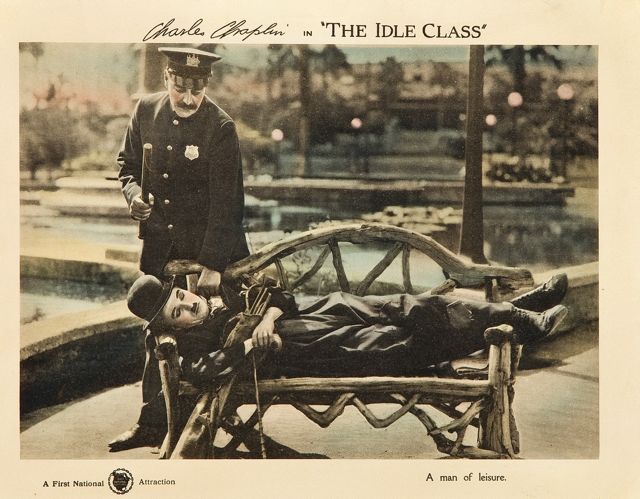

I'm a big fan of the classic Universal monster movies, especially the ones that were popular enough to spawn sequels, because it's so interesting to follow the permutations of the original formula as the franchise played itself out, usually ending up in the arms of Abbott and Costello.

The first sequel in any series is often the most interesting. The filmmakers, coming off the original hit, usually had bigger budgets and more freedom to get quirky and personal. The Bride Of Frankenstein, James Whale's sequel to his Frankenstein, is certainly that filmmaker's most revealing and original work. The Daughter Of Dracula takes the old bloodsucking warhorse into wholly new thematic realms. Revenge Of the Creature, Jack Arnold's 1955 follow-up to his Creature From the Black Lagoon, is one of the oddest and most powerful of all American films.

The Creature in both films is an embodiment of pure id, violent and territorial but also intensely sexual. The many scenes of him swimming underwater have a balletic, sensual quality, which make him strangely attractive, despite his horrid physical features. His energy inevitably becomes focused on the female lead in the films, in an obsessive kind of lust that leads to his destruction. This woman is also often seen underwater, in a revealing swimsuit, and her balletic, sensual moves echo those of the Creature, creating a suggestive bond between them. The male leads, acting or doubled underwater, never share this physical grace, this kinetic melody of movement, with the Creature and the girl. It remains horrifying to think of the Creature and the girl coupling, but the idea is not without its perverse appeal, its oneiric logic.

[It should be noted that Ricou Browning, who did all the underwater work in the Creature suit, in all three films in the series, is almost single-handedly responsible for the monster's appealing sensuality. Browning had worked in water shows, those mixtures of athletic feats and choreographed spectacle, just as Esther Williams had, and like her had learned in them the curious art of underwater dancing.]

All these elements were present in the original Creature From the Black Lagoon, but in the sequel they rise to the surface, as it were, dominating the film. The plot becomes an afterthought, characterization becomes an afterthought — it's the images of subaqueous sexuality, the transgression of boundaries between land and water, that drive the film.

The result is a kind of dream vision, by turns lyrical and nightmarish. It seems to have been made from the depths of the collective unconscious, and also from the depths of Jack Arnold's subconscious.

Arnold was apparently an incorrigible and crude skirt-chaser. Lori Nelson, who plays the vexing lead in the film, says that on location he installed her in a motel room next to his with a communicating door, asking her to leave the door unlocked at all times in case he needed to “consult with her about the script”. (She kept it locked at all times, of course, and asked her hairdresser to share her motel room with her for further protection.)

Arnold, swept up in cinematic images of an uncontrollable lust rising from the depths and stalking a sexy babe in the heart of civilization, was clearly getting in touch on some level with his own unruly id, and with his self-hatred in connection with it. The Creature remains dreadful and must die — at least provisionally — though we sympathize with its relentless devotion to pulchritude, which has a tender, almost pathetic side. In The Seven Year Itch, the Marilyn Monroe character goes to see Creature From the Black Lagoon and remarks afterwards that the Creature wasn't so bad, that “he just wanted to be loved”.

That's probably how Jack Arnold would have excused his desire to “consult” after hours with Lori Nelson about the script — that desire may well have been what the script was all about, for him. And how satisfying for him to kill off the Creature at the end, knowing that in a Universal monster-movie cycle, the primal id never really dies . . . as long as there's an audience out there which will pay to see it resurrected.

In any case, Revenge Of the Creature remains a kind of unconscious masterpiece, or masterpiece of the unconscious — beautiful to look at, sexy, disturbing and, in its own crude terms, profound.

My Mom and my sister Lee at Bluewater, an exceptionally good seafood restaurant on the Intracoastal Waterway at Wrightsville Beach, North Carolina. I find myself thinking of the crab cakes served there . . .

For some reason I find images of naked women underwater peculiarly erotic. It must be connected to whatever impulse it was that prompted the ancients to imagine that Aphrodite had been born from the foam of the sea, an idea that makes perfect sense to me.

. . . on the North Carolina coast.

You can't imagine how excited I am about this . . .

. . . loves to entertain family and friends with her exquisite water ballets, performed in her pool. Here she demonstrates her famous “swan pose”, which never fails to bring a gasp from onlookers.

. . . looking stylish on the patio of my sister Anna's house in North Carolina.

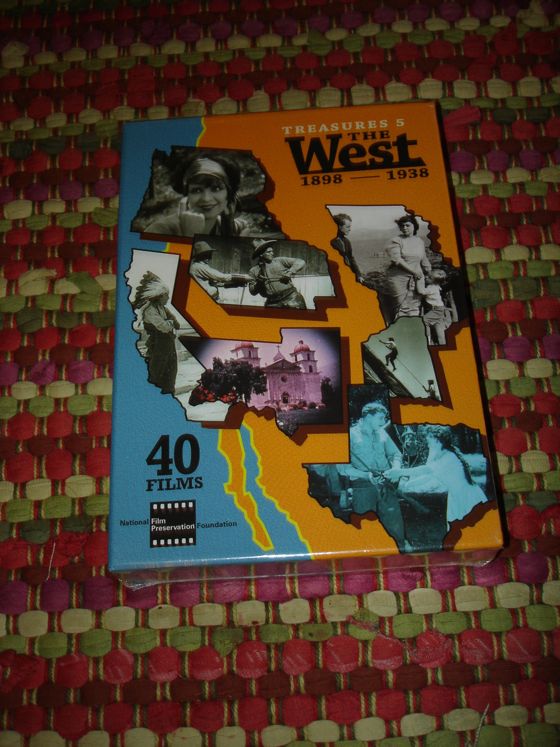

Curiously, it was cinema, a supposedly new art form, that remained, along with jazz perhaps, the most self-confident of arts in the 20th Century, never for a moment doubting its task, which was traditional, conservative even, humane and popular, unlike the older “high art” forms which became the province of ever-dwindling cultural elites.

Hiding behind the mask of its purely technological novelty, it carried on the art projects of the 19th Century without shame — Victorian academic painting, Victorian theater (especially Victorian spectacle-theater), program music and the variety stage.

This has to be one of the most astonishing sleight-of-hand acts in the whole history of art.