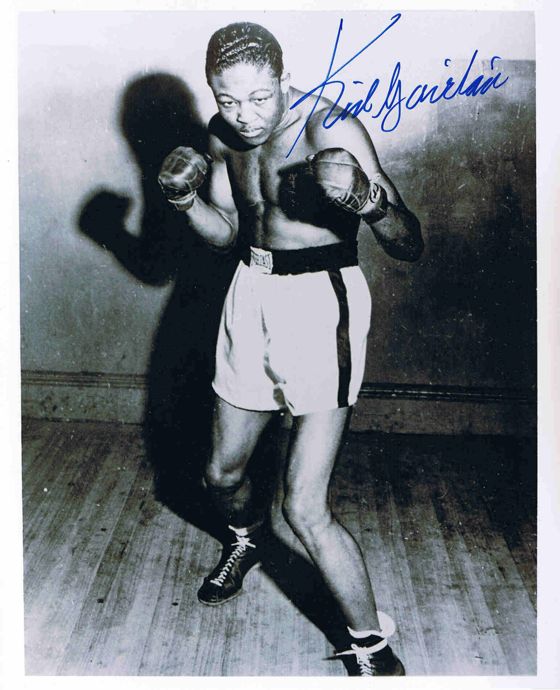

Gavilan is the man credited with inventing the bolo punch. He said the

punch, which was half hook and half uppercut, was developed by years

spent cutting sugar cane with a machete in his native Cuba.

Gavilan is the man credited with inventing the bolo punch. He said the

punch, which was half hook and half uppercut, was developed by years

spent cutting sugar cane with a machete in his native Cuba.

Bonnie McCarroll, female rodeo rider from the early half of the last century, is famous for two things. The first is the amazing photograph above, taken in 1915 when she was thrown from a bucking bronco — and not badly hurt. The second is her death fourteen years later from a very similar accident.

In the old days lady bronco riders used to tie their stirrups together under the horse's belly for greater stability. On her fatal ride, Bonnie's horse leaped up then plunged to the ground in a kind of somersault, slamming Bonnie's head against the ground and knocking her unconscious. The horse got up again, with Bonnie still in the saddle, and Bonnie's boot got stuck in one of the tethered stirrups when a fellow rider tried to get her off the horse. Then the horse bolted, knocking Bonnie off and dragging her around the arena with her foot still wedged in the stirrup. She died in the hospital of brain injuries ten days later.

She was thirty-four years-old at the time — a woman of true grit.

A few viewings of the movie Super 8 prompt some musings from Paul Zahl (of The Zahl File) on the layers of life and on the difficulty of telling a facade from a foundation:

BACK TO FRONT IN SUPER 8

There are two stories within the movie Super 8. Which is the “front story” and which is the “back”?

There are two different realities depicted in Super 8. Which is true and which is false? Or rather, which is really real?

The two stories of Super 8 are the story of childhood, on the one hand, and of adulthood, on the other.

Joe is grieving the death of his mother, Charles wants urgently, to the exclusion of all else, to finish his movie, Cary loves to blow things up and burn things down, and Alice wants to be able to love her father. The children see nothing else, hear nothing else, and can talk of nothing else. The children are immediate with their feelings: there is no monitor governing their emotions. Moreover, the children find out, long before anyone else does, what's really going on.

The adults, on the other hand, are trying to control everything. The USAF is trying to control the world. Joe's Dad is “scrambling” — the current word — to control the panic of the town. The merchants of Lillian, Ohio are calling their insurance companies; meeting fruitlessly and interminably to discuss the problem, and with all the wrong information; and blaming “bears” or the Soviets. No adult has the slightest idea what is going on, except the local science teacher, who understands it from the inside out.

The children, in other words, are right with the truth, from start to finish. Instinctively, because of their ungoverned feelings — not a bad thing in this movie — they are never wrong, about any aspect of their lives. I believe this is true in life. “A little child shall lead them.” “Unless you become as a little child, you shall in no wise enter the kingdom of heaven.”

The two stories in Super 8 reflect the two realities of Super 8. The children see everything as it is, or you could almost say, only as it is. The adults, so full of worry and fret, so completely engrossed by conflicting supposed obligations and responsibilities, see nothing as it is. The cost to the adults is the near destruction of their lives and town. The gift to them from the children is knowledge, understanding, and reconciliation.

Super 8 is also monistic. It is a monistic work of popular art. By this I mean that it portrays love and compassion — sounds like a cliché, doesn't it? — as universal to all creatures, including alien monsters. The playing field of love is level.

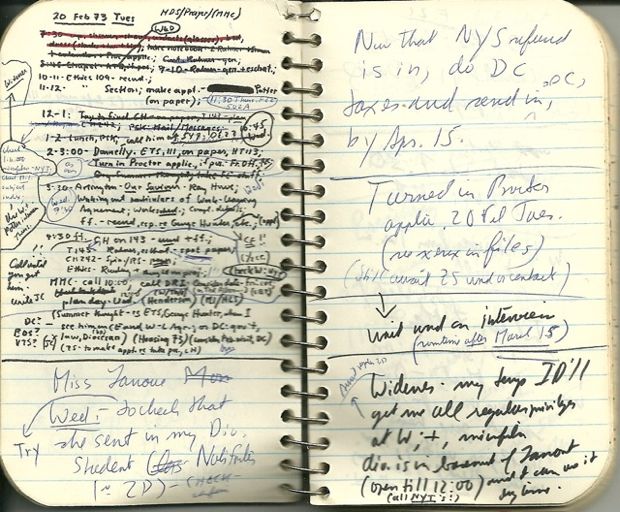

Recently I came across ten little notebooks, notebooks for a person's breast pocket, which I used for my to-do lists during the Winter and Spring of 1972-1973. I was a recent college graduate and quite confused, about absolutely everything. A lot was going on, and just barely underneath the surface. It mainly concerned girls, and sex; not to mention who did I wish to be and become. I was striking out on almost every front, though there were a few shafts of light oddly breaking through. But those notebooks, goddammit!

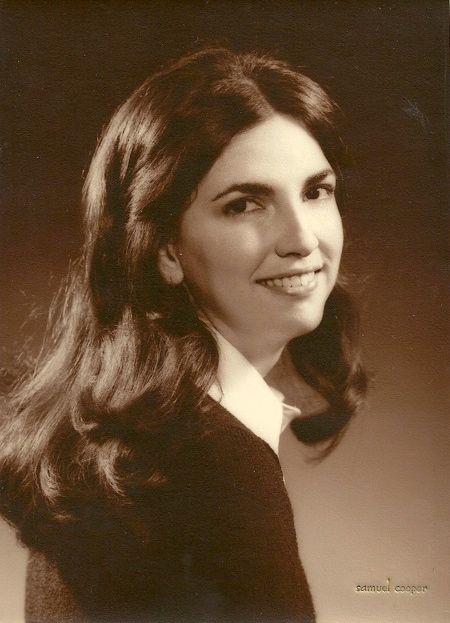

I read them again. They are lists and lists of “urgent” things to do: letters of recommendation to get, applications to complete, courses to take, contacts to make, professions to pursue, taxes to file. Someone named “Mrs. Watson”, the identity of whom I now have no idea but who was probably the administrative assistant to some academic dean, gets innumerable mentions. Yet the only thing I was really thinking about, I mean really, was the person who would later become my wife [below, in a picture from the time]; and how she fit in with some possible other person, and so on.

What I am saying is that my little notebooks carry a “front story”, i.e., “process”, “Mrs. Watson”, and getting into some program or school; and they carry a “back story”, i.e., the core relationship of my future life.

But which was really “back” and which was “front”? It was the opposite of what I thought at the time. The career story was the back story, tho' I conceived it to be the front. The Love Story was the front story, tho' I thought it was the back.

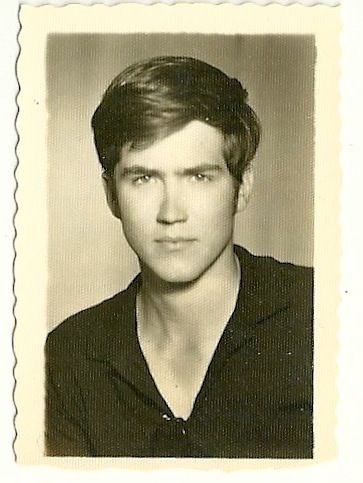

This is a lesson for me from life. If only I could go back to 1973 and live the right emphasis. Just like in Super 8, what you think is the back story is really the only story. [Below, Paul in the Seventies:]

Each of the four times (so far) that I have seen Super 8, I have come home from the theater and dug out my old issues of Famous Monsters. Like the Aga Khan, they are worth their weight in gold. I even found a second issue that had been autographed by Forrest J. Ackerman on the Sacred Day that Lloyd Fonvielle, Bill Bowman, and I were invited to lunch with him.

That's reality. That's the front story. If I could only go back to the future.

Facebook friend Amy Harper becomes face-to-face friend, thanks to the miracle of modern air travel.

A stupendous night on the town, with steaks and a bottle of Tavel at Mon Ami Gabi, then poker at the Venetian. Amy told me her biggest problem as a poker player was being too conservative, but on the first hand she played she went all-in. Lost. The next big hand she played she also went all-in. Won big. Finally got felted on another all-in.

What a gal.

It’s rare to read a work of sociology that makes you cry, but The Great

Good Place by Ray Oldenburg is such a work. Even the title touches my

heart, describing as it does a place and phenomenon which has been all

but eradicated from American life by urban planners and suburban zoning

laws . . . the local tavern, coffee house, diner, corner store, soda

fountain . . . the “third place” set in between home and work where the

sometimes overwhelming confinement of the former and the often

stressful environment of the latter can be mediated by informal

conviviality with a small voluntary community of fellow citizens.

A true third place must be convenient, not dependent on traveling a great

distance to reach, so its gatherings need not be planned — it must be

utterly inclusive, public, welcoming, and it must have regulars who

frequent it by happy choice and not out of any sense of obligation.

Whatever its physical ambiance might be, it becomes cozy and warm

through sociability, free and easy conversation, a sense of belonging

not maintained by any rules except those freely chosen by each

individual.

Oldenburg’s valuable synthesis of sociological insight into the third place, and

the dire consequences to the quality of American life brought about by

its demise, is also a quiet Jeremiad against the society, against all

of us, who have allowed this catastrophe to happen.

I think one reason people come so far in such numbers to Las Vegas is to

experience, in a brief concentrated dose, the free and easy mood of the

vanished third place — to drink and play with strangers who are not

really strangers, once greeted cheerfully and respectfully. Las Vegas

is America’s lost mythical corner tavern, with the naughty calendar on

the wall, poker in the back room, cheap food and drink at the bar. No

expectations, no networking, no snobbery — a true exercise in

democracy, inclusiveness, civility amidst diversity.

It’s a fantasy, of course, since the unique mood of Las Vegas is not

integrated into the lives of those who visit here, and so can never

take the place of a real third place. It is a great good place, though,

where you can kick back a little, forget the troubles of the workaday

world, see a few familiar faces and have a friendly word or two with

almost anyone you meet, from any walk of life and any place on the map.

Oldenburg argues persuasively that we’re not really human, fully human, if we don’t have places in our regular day-to-day lives where that is possible . . .

My friend Deane Evans is in town for a conference and I met him for drinks with two of his colleagues at the View Bar in a corner of the Aria Hotel lobby at City Center. What the bar has a view of is the Aria Hotel lobby.

Deane and his pals had convened in Las Vegas to confer on subjects related to energy efficient building, on which all of them are professional experts, but their after-hours specialty is making each other laugh. Deane has been making me laugh since we were boarding school roommates in 9th grade so it was fun to see him engaged in some high-caliber competition.

This being Las Vegas, the hilarity had to be shared — it was important to make busty cocktail waitresses and cab drivers and waiters and maitre d's laugh as well. All this was done in due course.

A rollicking conversation with a chatty cocktail waitress at the View Bar led to a dining adventure on the other side of town at a locals' restaurant she recommended, Casa di Amore. It's located in a wasteland of isolated establishments and mini-malls on an eastern stretch of Tropicana Avenue. (Directions to the Casa di Amore included the fact that it's right next to The Gun Store, which has a lighted sign featuring a large and scary-looking automatic rifle — it seemed to be assumed that everyone, even if they were unfamiliar with the Casa di Amore, would know where The Gun Store was.)

The restaurant was sublime, with its 80s decor intact, a lounge singer doing really good Tony Bennett and Frank Sinatra covers, hearty Italian food and a staff which was only too happy to aid and abet what had become a drunken (yet always impeccably witty) carouse. When Deane asked the waiter for directions to the men's room, the guy told him to step outside, walk around the side of the parking lot and use the bushes there. The maitre d' sent us an extra bottle of Chianti on the house, just to keep the spirits high.

Such was dinner at the “House of Love” — such is Las Vegas.

“We'll find 'em. Just as sure as the turning of the earth . . .”

Every home should have a special bar, well stocked with a selection of Mexican beers, por el huésped de honor . . .

. . . rarely gets its due in art.

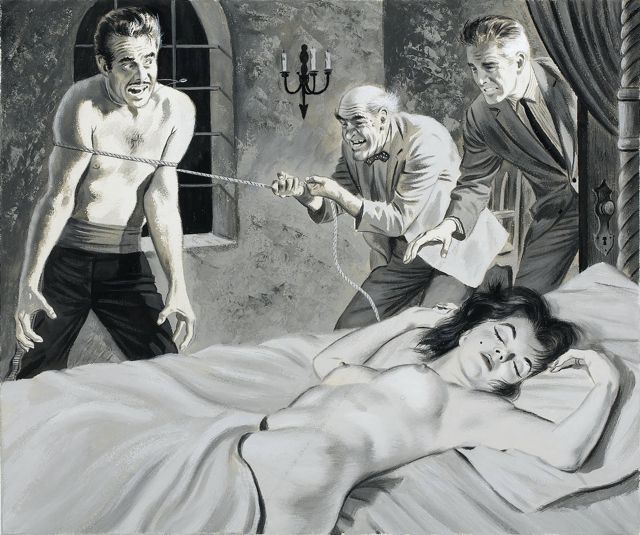

Illustration for Men's Adventure magazine, 1964, by Bill Edwards.

. . . to think about Jane Greer, coming out of the sun into La Mar Azul.

That guy had a world of talent.

And it's just . . . across . . . the borderline . . .