If you're not a fan of B-Westerns, it's probably impossible to explain their appeal to those of us who really love them. Their plots tend to be simple, some might say simple-minded, with cardboard-thin characterizations and clumsy dialogue. The acting can be clumsy, too, even by good actors — it's hard to speak clumsy dialogue with conviction. And yet . . .

. . . they tend to be beautifully photographed, at least in the outdoor scenes, with regular displays of superb horsemanship. Indeed, the action sequences on horseback are at the heart of these films, and like the transporting arias of operas with dumb plots, they can redeem much. (It's no accident, I think, that Westerns used to be called horse operas.) Technically impressive in so many departments, they still have the air of being made casually, by people who are enjoying themselves. They mix elements with insouciant ease — introducing songs at the drop of a Stetson, or outlandish costumes that clash with more authentic gear.

They were the testing ground for actors being groomed for stardom, as well as the dumping ground for stars who'd fallen from the industry heavens. You have the pleasure of seeing familiar faces working up their chops at the beginnings of their careers, and old favorites respectably earning paychecks on their way out.

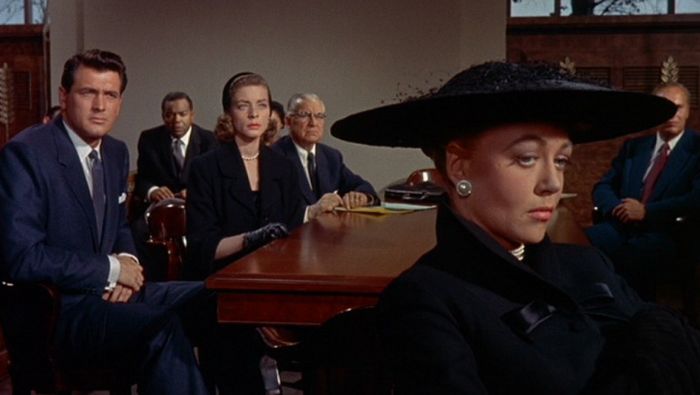

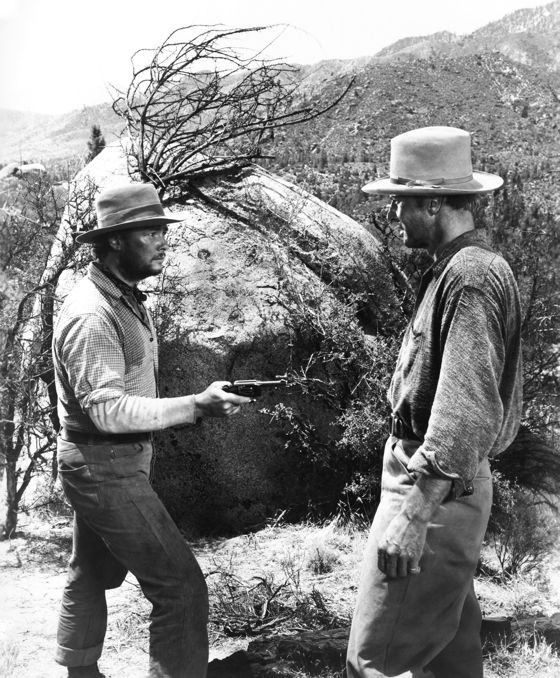

The Warner Archive has just released a ten-film collection of B-Westerns featuring Tim Holt — one of the most appealing of B-Western stars. Holt appeared in a handful of films that must be accounted among the greatest ever made, like The Magnificent Ambersons (above) and The Treasure Of the Sierra Madre (below), but he was never comfortable in Hollywood and had no great ambitions to be a star.

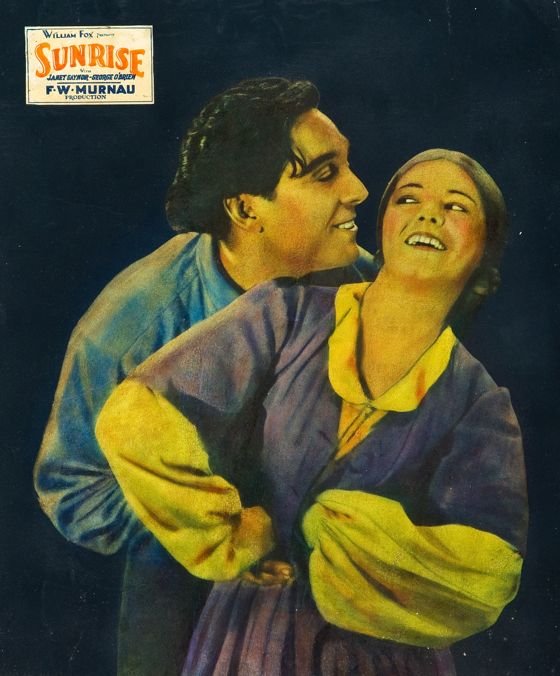

He liked horsebacking, though, and seems to have been content to grind out B-Westerns in rustic places far from Gower Gulch. He started out playing second leads in such films — like the earliest one in the Warner Archive collection, The Renegade Ranger, from 1938, which stars George O'Brien, who achieved screen immortality in the silent era in films like Sunrise and The Iron Horse.

In The Renegade Ranger Holt plays a callow, peevish youth with a dose of innocent charm, which will remind viewers of his role in The Magnificent Ambersons. He's much more comfortable in these surroundings than O'Brien, who seems a bit out of place in a talking picture, delivering his lines awkwardly but still managing to come across as a hell of a nice fellow. It's easy to see why Holt would later be tapped to star in his own series of B-Westerns.

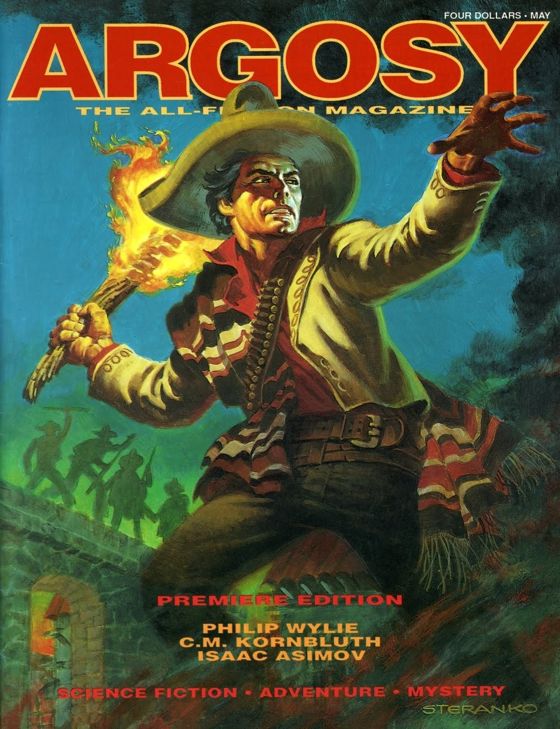

Rita Hayworth plays the female lead in the picture — a Spanish-American outlaw who makes her first appearance in a black silk blouse, trousers and a Gaucho hat, brandishing a six-shooter. The outfit is delightfully surreal and vexing. Hayworth delivers her lines stiffly but carries herself like a star, as trained dancers often do. Just watching her move onscreen is captivating.

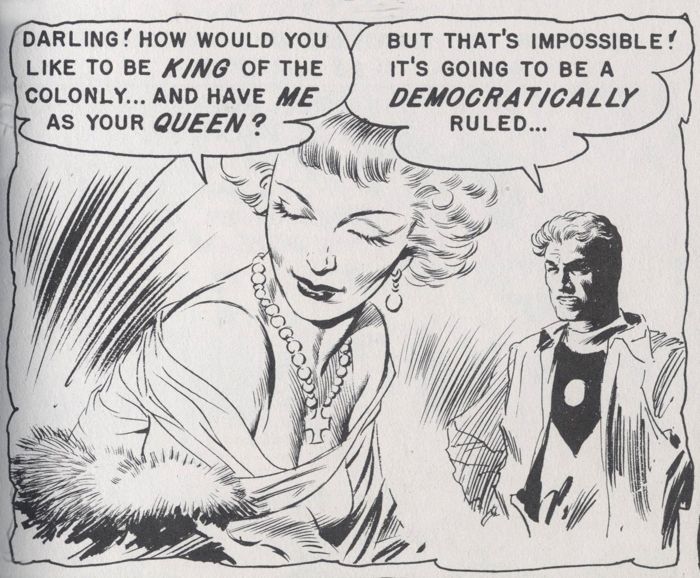

The film takes the side of Spanish-American ranchers whose land is being stolen from them by corrupt politicians — this is what has set the Hayworth character against the law. There are no stereotyped banditos in sight, which is refreshing, and must have been gratifying to Miss Hayworth, herself of Spanish heritage.

There's a lot of galloping around, a lot of shooting, a few songs, including a Western swing number, and a Spanish dance (not by Hayworth) with castanets. The plot resolves itself predictably. There is nothing much at stake in the drama beyond some misunderstandings that are easily resolved when the time comes for them to be resolved.

But, boy, what fun it all is.