The Coen brothers are known for their dark humor and bleak view of the world, but in recent years they have become increasingly obsessed with the mystery of goodness. In the desolation of a North Dakota winter, vicious killers stalk the land, and there suddenly is Marge Gunderson, a paragon of decency and courage. Why? Why is there a Marge Gunderson?

This is essentially a religious question, in the sense that it has no logical, rational answer. The temptation of theology is to supply logical, rational answers to religious questions, but it's the unanswerable questions that move the heart and change lives. That's why the Bible is long on stories and short on theology, why Jesus taught with parables instead of intellectual arguments.

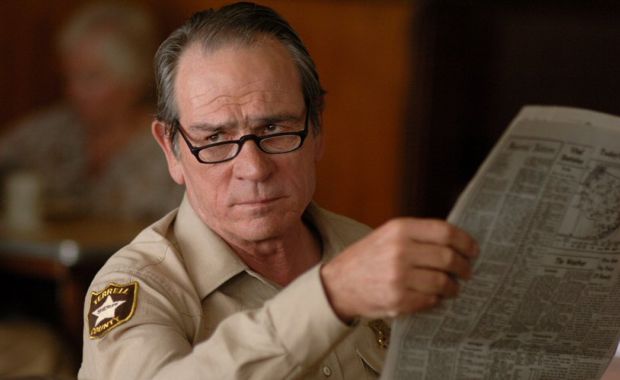

The Coen brothers' film No Country For Old Men is almost a reprise of Fargo — without the comedy this time, and with a much darker and more terrifying view of the evil stalking the borderlands. The figure of the good sheriff, played by Tommy Lee Jones, who seems to stand alone against the horror, is even more mysterious than Marge was.

He seems to possess some supernatural power over the Bardem character's pure wickedness — his very presence seems to be able to make the Bardem charcter vanish into thin air — but it's a power that even the Jones character doesn't understand. There is a suggestion that his decency and courage are outdated virtues, on the verge of being overwhelmed by the world's evil. And yet they linger . . .

In A Serious Man, the Coens take on the Book Of Job, the Bible's great story of a man who clings to righteousness in the face of an implacably destructive universe. It makes no sense — it is, yet again, a mystery to be puzzled over.

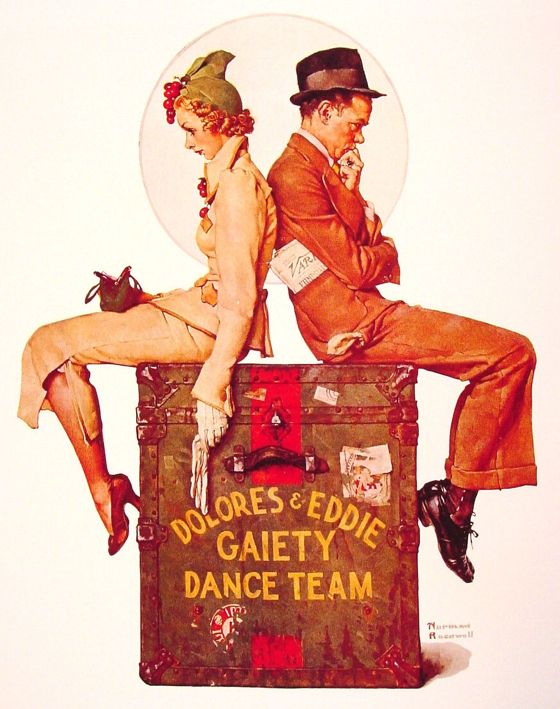

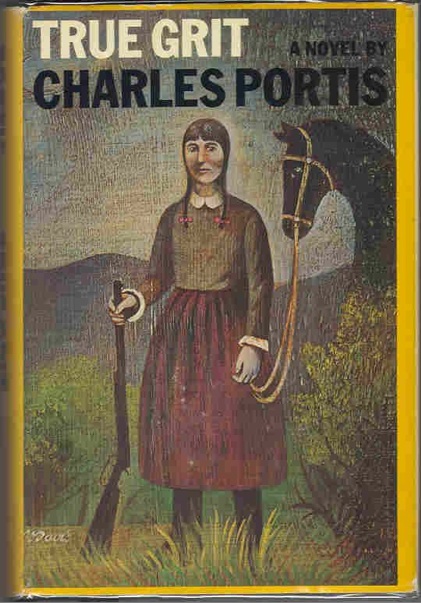

In Charles Portis's novel True Grit, the Coens found a text ideally suited to their late-period themes. A self-righteous and vengeful little girl meets up with a violent and none-too-virtuous law officer, and somehow they find a way to love each other. Their mission of harsh justice is infected with grace, a grace neither of them really understands, except on a level beneath conscious thought. They part ways after their adventure, but the little girl lives the whole rest of her life in the glow of one great act of love on the part of the least likely of men . . . a kind of redemption for both of them by the unexplainable appearance of goodness.

The Coens use the hymn “Leaning On the Everlasting Arms” as a musical motif throughout the film, and Iris Dement's recording of it comes at the film's end, summing it all up in a way. The phrase “everlasting arms” is from the Old Testament, and is used in the hymn as an image of Christian salvation, but the use of the song here is not theological in any sense. Mattie Ross's conscious religion is cold, judgmental and unforgiving — Rooster Cogburn's religion is non-existent. There is no theology in what saves them, because what saves them is irrational. The everlasting arms are just there, without explanation — the way Marge Gunderson is just there.

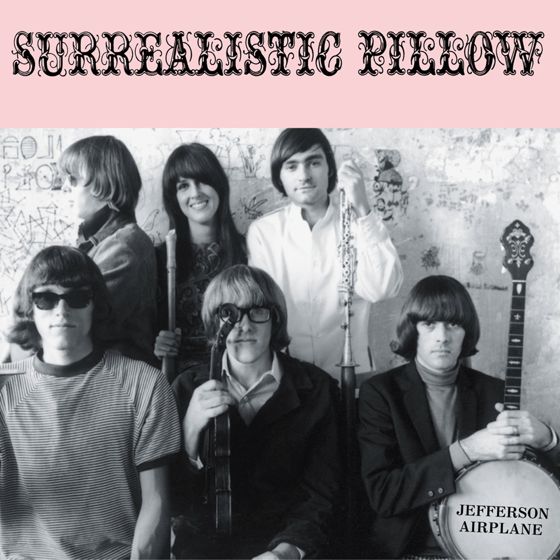

A key to all this can be found in the figure of Rabbi Marshak in A Serious Man. He is the ancient and remote fount of all wisdom, but unavailable to the film's Job figure, who can't get an appointment to see him. But his son is granted an interview after his bar mitzvah. The old sage sighs and then, improbably and hilariously, quotes a line from a Jefferson Airplane song — “When the truth is found to be lies . . .” And just when you expect wise council on this subject, the rabbi breaks off, trying to remember the names of the members of the Airplane.

So much for wisdom — almost. Ending the inscrutable interview, the rabbi gives the kid a portable radio, and says, “Be a good boy.” So — when the truth is found to be lies . . . be a good boy.

There is no suggestion that this will restore truth to the world, or make a triumph out of life. It's more a statement of faith — that goodness, like the Dude, abides, and that it may be the only mystery worth contemplating.