Christmas, New York, 1908

AN HENRI DE TOULOUSE-LAUTREC FOR TODAY

In Bed, The Kiss, 1892

TIME FOR CHRISTMAS IN THE HEART

Let it spin, let it spin, let it spin!

THANKS

Streams of mercy never ceasing call for endless songs of praise . . .

FIRST THANKSGIVING

And the update . . .

AN AUDUBON FOR TODAY

Wild Turkey

AN N. C. WYETH FOR TODAY

Thanks to Golden Age Comic Book Stories . . .

MAUDE FEALY

With thanks to Little Hokum Rag . . .

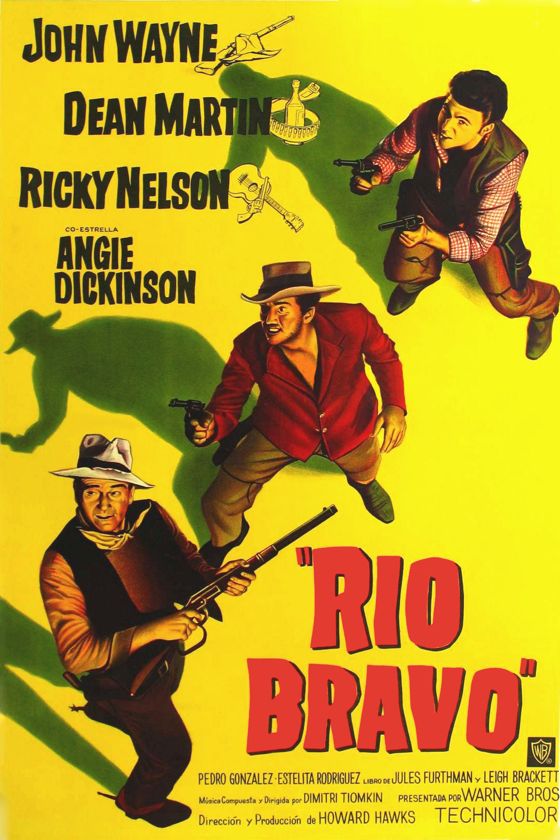

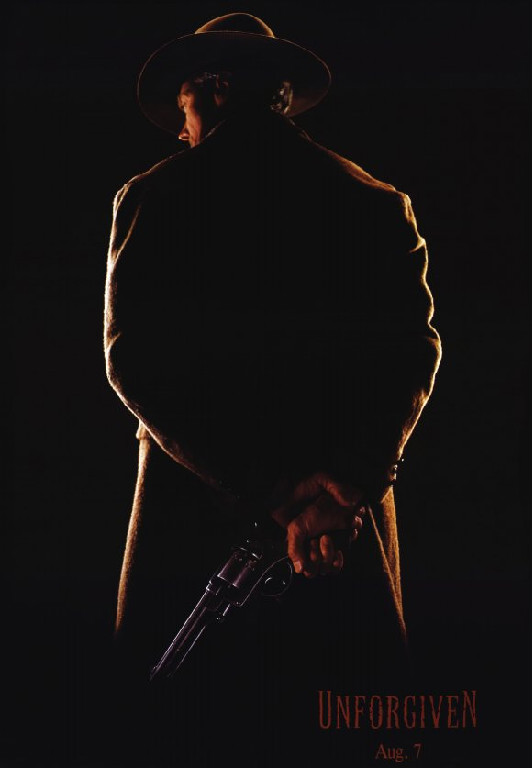

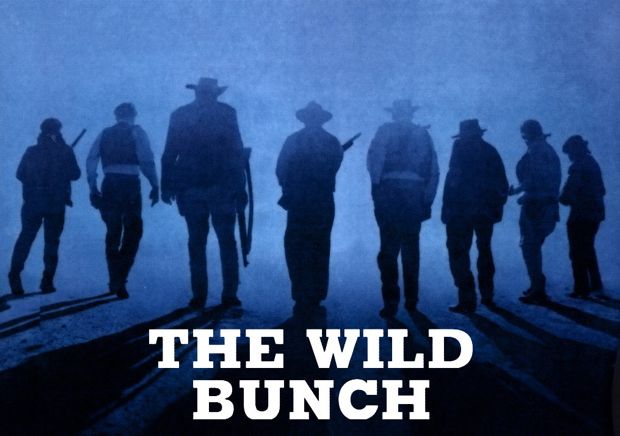

A WESTERN MOVIE POSTER FOR TODAY

A GIRL WITH A GUN FOR TODAY

RIO BRAVO

Howard Hawks's Rio Bravo, from 1959, is many people's favorite Western, and there has certainly never been one that's more entertaining. Hawks famously said that it was his answer to High Noon, which he found irritating because its hero sheriff ran around begging the citizens of his town to help him with his job. Sheriff John T. Chance in Rio Bravo, played by John Wayne, pointedly refuses help from the citizens of his town on the grounds that they're not professionals and would only get in his way. (He already has two allies — professional but flawed, just to make things more interesting — and picks up a third along the way.)

This dialectic is a little silly — there are obviously situations in which each approach would be appropriate — but Chance's is a lot more appealing, because it's closer to the classic Western idea of the hero. High Noon is about a town trying (and failing) to make the transition from frontier outpost to civilized community. Rio Bravo is governed by a different vision of the West, in which community in that sense is irrelevant — individual initiative and responsibility are the central and decisive issues.

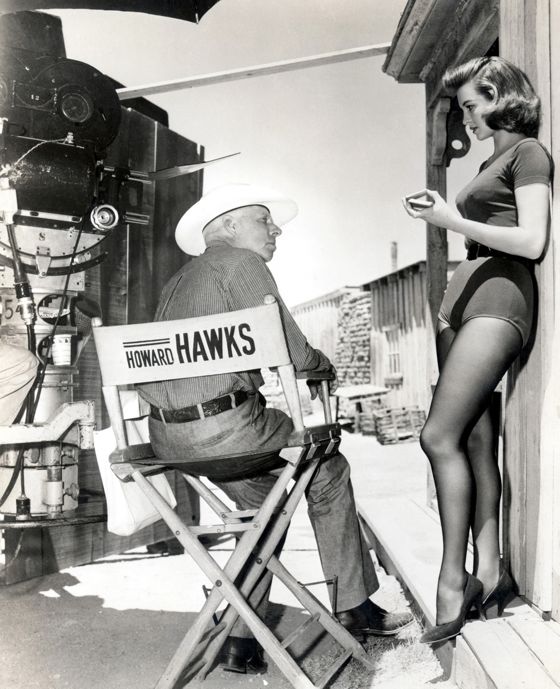

Chance's attitude also reflects a recurring theme in Hawks's work — a celebration of professionalism, of people who know how to get the job done and do get it done, however cynical they may be about the job itself. The small, closely-knit team, dedicated to a particular objective, is important to Hawks, along with the mechanics of teamwork — society as a whole doesn't concern him all that much, and is often presented as indifferent or corrupt, as it is for the most part in Rio Bravo.

Sex in Hawks's work is also more a matter of teamwork than romance — a game for two that has to be played well, and with a certain amount of diffidence. Hawks's typical women aggressively pursue men they're attracted to, but expect to be amused in return. Angie Dickinson is the hard-boiled dame “Feathers” who pursues Chance in Rio Bravo, asking nothing more than his engagement and encouragement for as long as things last. She's a virtual reprise of the Lauren Bacall character in To Have and Have Not, a drifter and adventurer who's intrigued enough by the hero to pause for a while in her wanderings to play with him.

Feathers initiates the first kiss in Rio Bravo, which Chance responds to almost passively. Then they kiss again and he's more active, at which she pronounces herself satisfied — “It's better when two people do it.” It's a direct echo of Bacall's famous line in To Have and Have Not in which she tells Bogart that kissing is “better when you help”.

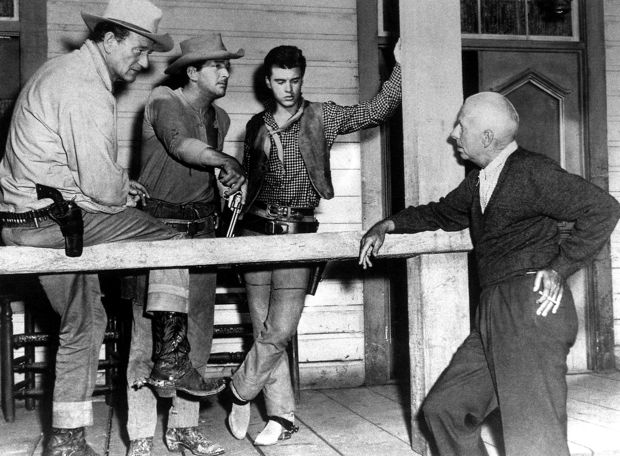

Dean Martin gives a surprisingly strong performance as Dude, a broken-down deputy who has to rehabilitate himself in order to help his friend Chance. Ricky Nelson plays a hot-shot kid gunslinger whose professionalism impresses Chance and leads them into an inevitable alliance.

Nelson's performance is lackluster — he's in the film for marketing purposes — but Hawks uses Wayne's authority as a star and Western icon to lend Nelson's character “Colorado” substance. If John Wayne approves of the kid and takes him seriously, who are we to second-guess him? Colorado has a moment of fancy gun-play in a shootout, but his heroism doesn't really register until Wayne tells the other guys how good Colorado was.

Nelson's presence, and the cheerful tone of the film, let us know that nothing much more than entertainment is at stake in the tale. John Ford is always interested in exposing the moral contradictions of his heroes, in examining the moral landscape of America itself. Hawks is just interested in hanging out with some cool people and watching them do their thing. Rio Bravo unfolds at a leisurely pace but is never dull for a moment — because the company is so good. The only real suspense lies in wondering if the characters will be cool enough when their big moments arrive. Of course they always are — and then some.

The spirit of fun that infuses the film is almost tongue-in-cheek — one can see in it a foreshadowing of the Sergio Leone approach to the Western, in which every Western cliché seems to have quotation marks around it, seems to be delivered with a wink. Unlike Leone, though, Hawks is never interested in subverting or upending the clichés — just in having some fun with them, in the most efficient and elegant way possible.

Molly Haskell has called Rio Bravo “a movie one loves and returns to as to an old friend” — and that's not faint praise for a film which lasts well over two hours and proceeds, as I've said, at such a leisurely pace. It's a “town Western”, too, one that never strays from the town it's set in, that takes place mostly in interiors and on one street on a studio lot. But Hawks explores this narrow geography thoroughly, makes us feel at home in it, and his cinematographer Russell Harlan lights it warmly. The film makes us cozy and comfortable, gives us time to know and savor the quirks and qualities of its characters.

This may make it seem like a simple film, but it's hardly that — the skill required to make something this “simple” so consistently fascinating and enjoyable is hard to value or praise too highly. It takes the kind of cool and impeccable professionalism that Hawks admires and celebrates so agreeably in his protagonists.

MAJESTIC

A new Majestic Micro Movie by Harry Rossi — a movie as majestic as the sea itself!

Watch it here:

The Ocean

DIANA THE HUNTRESS

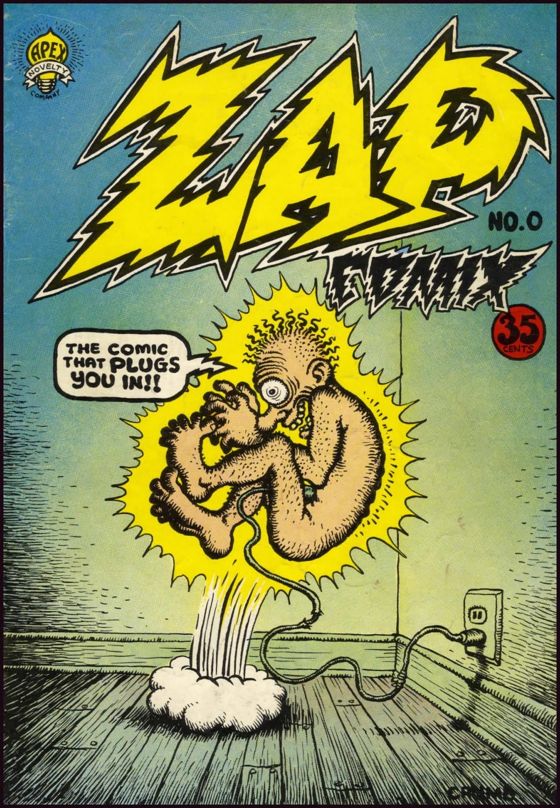

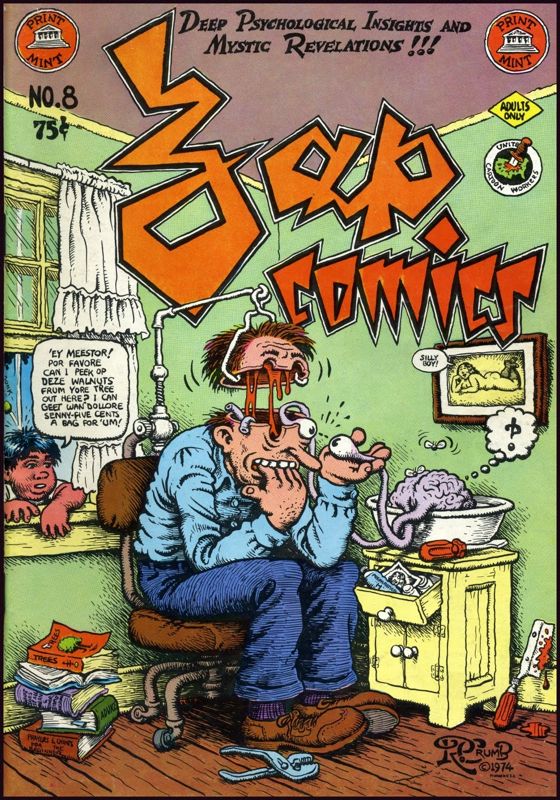

ZAP

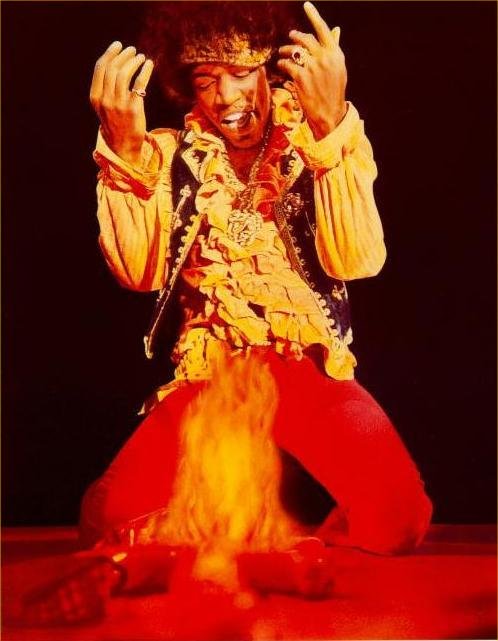

I was 9 when the Sixties began, 13 when they began in earnest with the assassination of John F. Kennedy and the advent of The Beatles. The decade sucked up all of my teenage years and brought many cultural shocks, from the Civil Rights Movement to Dylan's minatory prophesies, more assassinations, fighting in the streets over the Vietnam War and the sublime derangements of Jimi Hendrix and Jean-Luc Godard.

I went off to college in the Bay Area in 1968, grew my hair long, wore Nehru jackets and sandals made out of tire treads. I eschewed illegal drugs — my little stab at non-conformity — but drank plenty of Ernie's Burgundy and took up the smoking of cigarettes. I hitch-hiked all over the country and once panhandled for spare change on a street corner — living out a fantasy of dereliction, all the while knowing that I had a nice middle-class family to return to if things ever got really desperate. (Such was the depth of hippie rebellion.) I was at Altamont where everything came crashing down in spectacular fashion.

In all that madness, I don't think any cultural artifacts impressed me as deeply as the works of R. Crumb. When I bought my first batch of Zap Comix at the City Lights Bookstore in San Francisco and began to devour them, I had a sense that I would never look at America and American popular culture in quite the same way again — and I never did. Crumb represented a permanent mind-fuck.

THE WESTERN: REX QUONDAM, REXQUE FUTURUS

The Western isn't dead — it never was. It abides, through fruitful times and fallow times — a rich soil always capable of putting up unexpected shoots.

A bestseller, like Larry McMurtry's Lonesome Dove, can inspire a classic Western, which the mini-series based on the book surely was. A great screenplay, like David Webb Peoples's Unforgiven, in the hands of a great director, can produce a critically-acclaimed box-office hit.

Unforgiven was much more than that, of course — it is now generally recognized as one of the greatest Westerns ever made, one that can stand comparison with the classics of the genre, and with all but the very best Westerns of John Ford.

Since Unforgiven was made in a fallow time for Westerns, it naturally reflects this. It is part of a tradition that arose in the Sixties when the Western seemed to be dying off as a viable commercial genre — the twilight Western. This tradition concerns aging heroes who set off on one last adventure, mirroring a feeling that the Western itself might be heading for the last round-up. Valedictory in tone, it actually wants to assert that the aging heroes are still with us, that their values still matter.

The twilight Western tends to be revisionist, painting a darker and grittier vision of the Old West than the older classics, and often incorporating a female perspective — these are its nods to modernity, on one level, but also its witness that the Western genre is still alive, still capable of evolving, of reflecting contemporary issues and ideas.

The makers of anti-Westerns, like Sam Peckinpah's The Wild Bunch, believed that the Western was played out, and proceeded to deconstruct it, to suggest that the Western myth was all a lie — that was their nod, or surrender, to modernity. It was a delusion, as the phenomenal success of movies like Lonesome Dove and Unforgiven proved, but a delusion with great cachet for filmmakers and studio executives who came of age in the Sixties and Seventies. For them, the thrill of killing off the traditions of their fathers festered and metastasized into an industry truism — modern audiences don't like Westerns.

The truth is that modern audiences don't like anti-Westerns, the only Westerns that present-day Hollywood thinks are cool. Every time a new anti-Western flops, it seems to confirm the truism. When a new Western that celebrates the classic virtues succeeds wildly, it's seen as an anomaly.

If the Coen brothers' True Grit, opening this Christmas, succeeds, Hollywood will not see it as the success of a Western. As a Hollywood producer recently remarked to a friend of mine, reflecting on a possible revival of interest in Westerns, “The Coen brothers are their own genre.” There's some truth in that, of course, but only up to a point, and that point is reached when the Coen brothers tackle a classic Western tale like True Grit.

Eventually, the glamor of the anti-Western will die out, with the rise of new generations of directors and producers untainted by the follies of the Sixties and Seventies. The Western will still be here, its soil richer than ever from a long fallow time, ready to produce a new harvest of stories and adventures. The passing of the twilight Western will signal the true renaissance of the form — new, young stars will take up the reins as protagonists of the revived Western, and blaze their own trails into the heart of America's most precious and enduring myth.