The tide is high but I'm holding on . . .

The tide is high but I'm holding on . . .

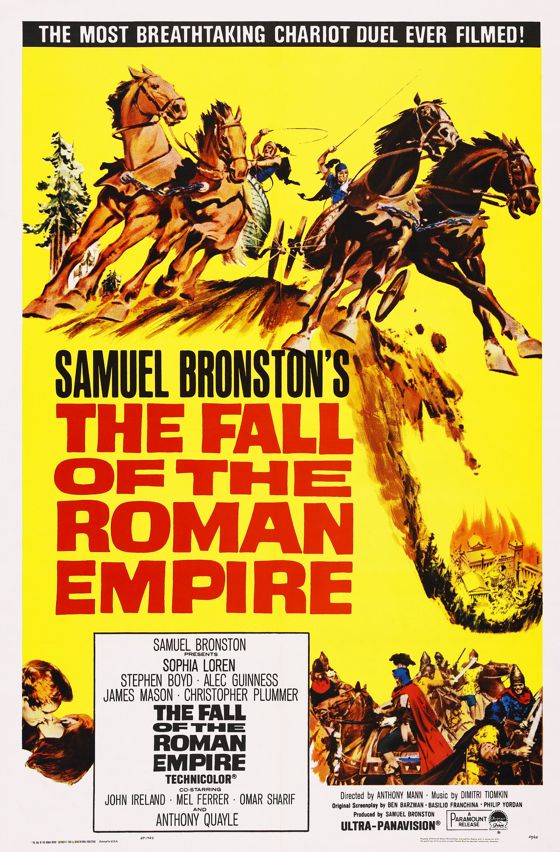

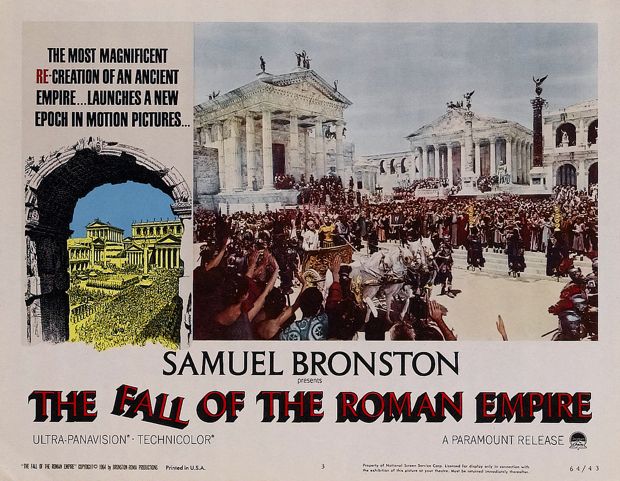

Magnificent in many ways, breathtaking visually in many sequences, Anthony Mann’s The Fall Of the Roman Empire, from 1964, is nevertheless an epic failure. Unlike the Roman Empire, the film’s downfall can be traced to a single cause — a single miscalculation in casting. A film as big as this needs an emotional rudder, a figure at its center the audience can steer by, and Stephen Boyd is just not able to be that. Very few actors could, but Boyd is singularly ill-equipped for the task.

Boyd had a slightly fey quality, a hint of weakness in the eyes and mouth, which worked wonderfully when set against the stolid heroism of Charlton Heston in Ben-Hur. It fueled the slight suggestion of a homo-erotic attraction between the two antagonists. As the heroic lead of The Fall Of the Roman Empire, by contrast, Boyd creates a kind of black hole of charisma at the center of the picture, especially since he is paired romantically in the story with Sophia Loren, who is, just in her own person, an epic of femininity. Between the Roman Empire and Loren’s empire of female flesh, Boyd doesn’t have a fighting chance.

Boyd was an actor of limited range, and heroic grandeur did not fall within it, as it did for Heston, limited as Heston may have been in other ways. (Heston and Kirk Douglas both turned down the Boyd role — either one of them, I think, could have saved the picture.) Boyd here summons at best the slick authority of a Las Vegas lounge singer — not someone one would entrust with the command of a Roman cohort, much less the rule of Rome itself. It doesn’t help that Boyd is given a preposterous hair-do, with curled, poofy bangs, obviously dyed. If this film hadn’t cost so much money, you might almost believe that the bangs were some kind of cruel joke slipped into the film by a prankster on the production.

The inadequacy of Boyd can’t quite sink the first half of the film, up to the intermission. This section, set on the frontiers of the empire in Germania, boggles the mind with its size and sweep and beauty. We will never again, in the age of CGI, see images like this on film.

The film shifts to Rome after the intermission and, despite a parade of staggering and mostly magnificent sets, unravels quickly as a drama. It becomes a test of wills between the neurotic Caesar Commodus, played with relish and wit by Christopher Plummer (below) . . .

. . . and Boyd’s Livius, his second in command. At stake is Livius’s love for Lucilla, Commodus’s sister, played by Loren, as well as the survival of the Roman Empire. It’s hard to care about either with Boyd as the protagonist in both struggles and a bit of a relief when Rome finally implodes.

Once you accept the film as a failure, though, you are free to appreciate its wonders — some of the most spectacular recreations of the ancient world ever committed to film, all shot with Anthony Mann’s usual genius for plastic composition and action. It’s a thrill, as well, to watch the way the camera worships Loren, who gives a very good performance here, along with a wonderful cast in almost all the supporting roles. Fans of Ridley Scott’s Gladiator will also discover that its original screenwriter David Franzoni found much of his inspiration for that film in The Fall Of the Roman Empire, set in the same period, with a number of set pieces and major story elements in common.

But, as I say, Mann’s film is a rudderless ship, narratively and emotionally — one soon ceases to wonder where it’s going, because, like the Roman Empire itself in its twilight years, it’s so obviously going nowhere.

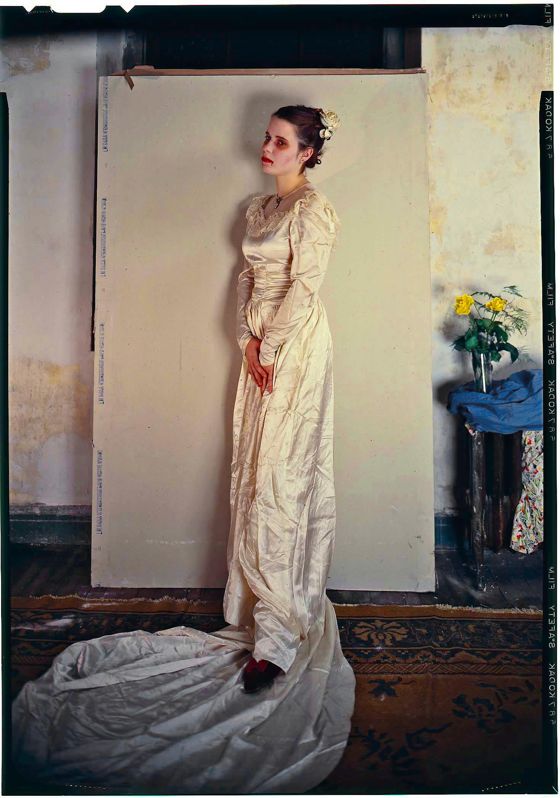

This is Eli Johnson, as she then was, whose latest birthday I wrote about here, on Halloween some years ago, when she was just 17 (and you know what I mean), photographed by Lang Clay.

The portrait is like a John Singer Sargent gone slightly awry.

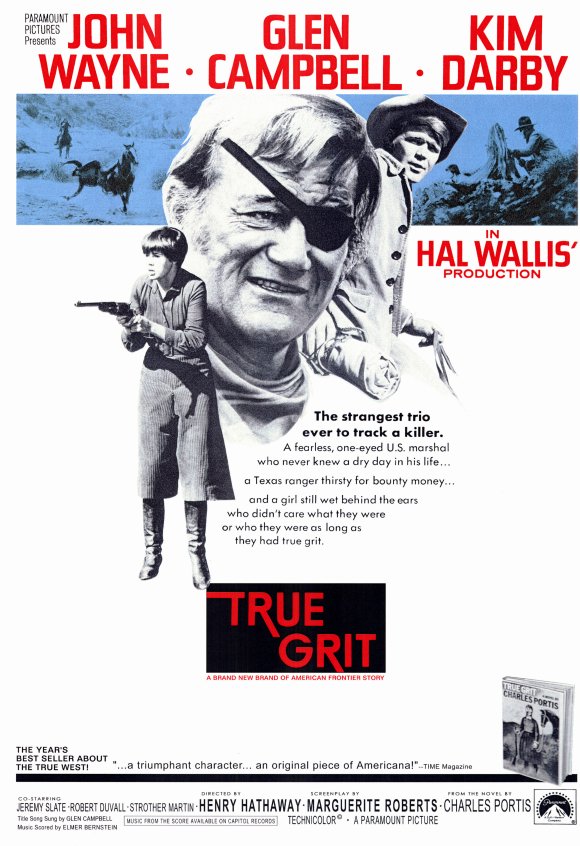

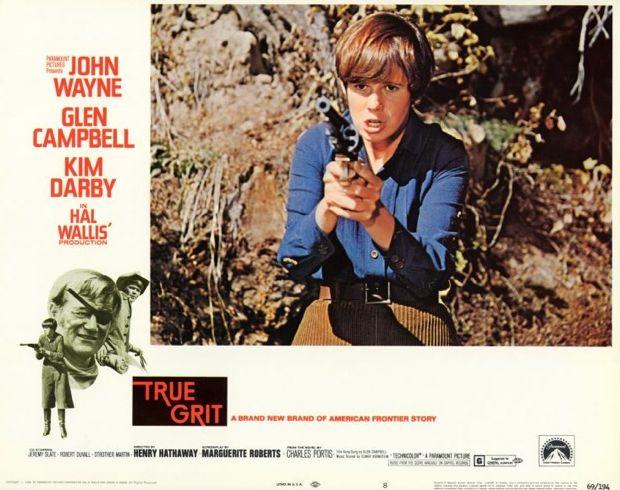

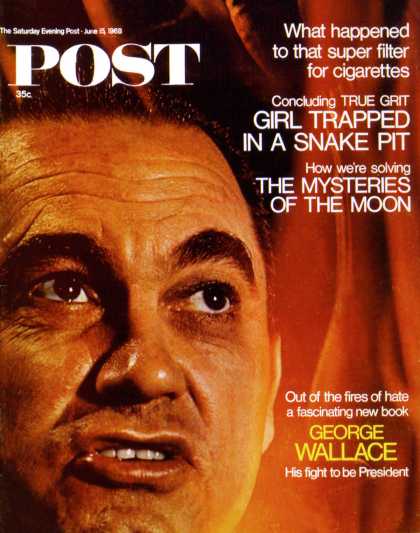

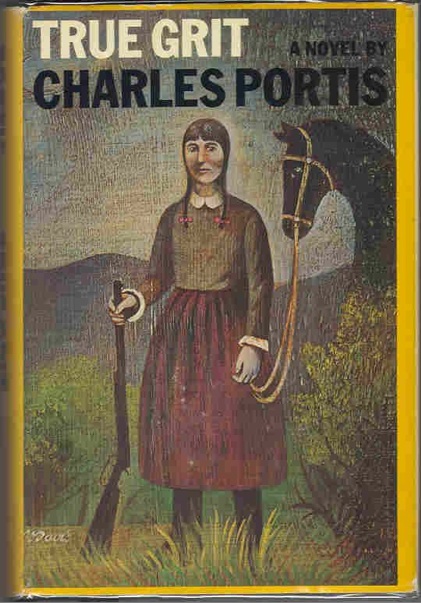

Henry Hathaway’s film True Grit, from 1969, is a wonderful entertainment, respectful of, if not exactly faithful to, the great Charles Portis novel on which it’s based.

The powerful emotional impact of the novel is achieved by indirection, by characters who don’t speak about what’s really going inside them because they’re rarely aware of it. We read their inner lives though their actions, which are often surprising, startling, even shocking. Hollywood is generally afraid of tales told this way, afraid that audiences won’t get the point, so the adaptation of True Grit brings the emotions and motivations of the characters to the surface. Paradoxically, this leaves the viewer with less to respond to.

It’s clear from the start in the film where the friendship between the teen-aged Mattie Ross and the grizzled frontier marshal Rooster Cogburn is going. It’s a pleasure to watch it go there, but one can’t fully enter into the journey as a participant. John Wayne, who won his only Oscar for his portrayal of Cogburn here, is exceptionally good, working against his usual buttoned-up hero’s persona, but reveals the character’s decent and genial side too quickly.

Kim Darby, as Mattie Ross, also gives a fine performance, but because Darby was 21 when she made the film, Mattie’s precocious self-possession can’t help but lose some of its edge. (In the book, Mattie is 14.) Glen Campbell, then a popular cross-over country singing star, was cast in the third lead as Le Boeuf, primarily as a marketing ploy one assumes. He acquits himself well enough, but always looks out of his league among the other fine supporting players like Robert Duvall, Dennis Hopper and Strother Martin.

Although Hathaway directs the film in a classical style, with beautifully composed images (discounting a few ill-advised zooms), the film tries in other ways to be contemporary. Elmer Bernstein’s score, often echoing the one he did for The Magnificent Seven, is generally light and buoyant — it doesn’t enforce the darker emotional currents of the tale. The script incorporates a lot of Portis’s fine dialogue but emphasizes the cheerful and comic side of the novel, at the expense of its paradoxes and contradictions. The disturbing undertow of the book is only suggested.

Paramount probably thought it was taking quite enough chances on this film, a Western with a strong female protagonist that featured John Wayne as a slightly less than heroic drunk — but in truth it was only keeping up with the times. In the 1960s, Hollywood and the culture were becoming self-conscious about the conventions of the Western in an era of national doubt about the American dream, undermined by a controversial war in Vietnam and rowdy social upheavals at home.

1969 also saw the release of The Wild Bunch, Sam Peckinpah’s savage and cynical deconstruction of the Western genre. True Grit was a big hit at the box office, The Wild Bunch not so much, but a critical favorite. The culture was clearly open to a different kind of Western. It’s a shame that filmmakers chose to follow in Peckinpah’s tracks, instead of Hathaway’s or even Portis’s. Dark and unconventional as the novel True Grit was, it still managed to celebrate, in its quirky way, the humane and noble values of the classic Western, introducing a convincing female perspective in the process. Portis’s vision might have led to a renewal of the Western film — Peckinpah’s led to its virtual destruction as a reliable Hollywood genre.

That's Bill Eggleston above, wearing the bow tie, flanked in the foreground by my friend Lily Chubb on the left and his daughter Andra on the right, at the reception for the opening of his show Democratic Camera at LACMA last week.

The exhibition originated at the Whitney Museum in New York a couple of years ago but has been expanded and beautifully hung at LACMA's Resnick Pavlion — it's certainly the best Eggleston show I've ever seen, with images from every phase of his work from 1961 to 2008. It gives a good sense of the scope and depth of his portrait of America, one of the most important artistic projects of our time.

I attended the show with my sister Lee, on the left with Lily below:

Bill seemed a little overwhelmed by the attention at the reception, and faded a bit in the crowded, stuffy galleries, but revived when he took up a position on an outside terrace. Lily's dad Cotty pulled me aside and suggested that if I had an extra cigarette, Bill could probably use it. When I offered him one he looked at me skeptically and said, “I didn't know you could smoke here.” I said, “You're the star of the show, Bill — you can do whatever you want to do.” He laughed. “Do anything I want and say anything I want,” he said.

He smoked. Nobody told him not to. An endless stream of admirers approached him to offer their respects. (That's me with Lily below.)

I first saw a large selection of Bill's work in 1971, before it was widely known, and realized immediately how important it was. The world's eventual embrace of it never surprised me, and nearly forty years later, his recognition as a master, in shows like this one and many others, doesn't surprise me. It probably doesn't surprise him, either.

[Image © William Eggleston]

Large as the LACMA show is, it represents only a small fraction of his work. Taken as whole, it will represent an extraordinary legacy to the future. He has a kind of calm about it all, a kind of satisfaction in his service to his art and his country. Personal celebrity doesn't seem to mean much to him — what he cares about is showing people what he has seen. He seemed gratified last week that people were looking at it.

If you live in the Los Angeles area, you should really go look at it for yourself.

My friend Eli Selden's birthday coincided happily with the opening reception of photographer William Eggleston's grand retrospective exhibition at LACMA, which I drove over from Las Vegas to attend. (That's Eli above on the left, with her oldest friend from Memphis, where she grew up.)

A bunch of friends and family convened for dinner at the Tar Pit on La Brea before the reception, and we had a fine time. The food was good and moderately priced, and people from every phase of Eli's life were on hand.

I first met Eli when she was a 16 year-old freshman at Yale (she's brainy) and she and I went on to share many remarkable adventures over the years in the dark jungles of Hollywood. She's known Bill Eggleston about as long as I have, having babysit his kids in Memphis when she was a teenager, so the occasion of the reception, which Bill attended, was like old home week.

Eli wore a dress with sparkles on it, and sparkled herself all night. Many happy returns of the day, kid.

On his recent trip to Paducah, Kentucky, Paul Zahl passed through Nashville and made a special trip to see . . . a Presbyterian church done in a very strange style. He writes:

This photo is a little dark, but was the best I could do given the

available lighting. Together with the First Presbyterian Church, also known as the Old Whaler's Church, at Sag Harbor, Long Island, this is one of the earliest Egyptian

Revival churches in America. Now known as the Downtown Presbyterian Church, it was designed by William Strickland in 1849.

It is directly across, or almost directly across, from the Capitol, in

the center of Nashville. Because Presbyterian churches are rarely open

during the week, I was doubtful that my friend Ray and I could get in but . . . dashing around the block to the church office, I found the

sexton. She was just “closing up”. Fortunately, she opened the

church, and I got in.

It is amazing. Central pulpit, large organ and organ case, classic

Communion table under the pulpit. I looked for the Mummy behind

the pulpit, but no dice. I am believing that Kharis rests directly under the pulpit. Wonder, too, whether the preaching in this church is

sufficient to waken him. I hope so . . . or maybe I don't.

I must say that the Egyptian Revival style in early 19th-Century American architecture was more or less off my radar, and the fact that it was used for Presbyterian churches seems delightfully odd.

Every time I drive west from Las Vegas my heart sinks as I approach the California state line because I know that, as a smoker, I will be treated in California like human scum. It's socially acceptable to be obese in California, to drink and drive, to abandon your kids and trade in your wife for a younger and more attractive one, to cheat your colleagues and collaborators out of money in a deal, but light up a cigarette and all the pathetic duppies who dictate social hygiene in the state will stare at you with arrogant disdain. You can be sitting on an outdoor restaurant patio within thirty feet of a street where hundreds of cars per hour pass by, but if you want to add a wisp of tobacco smoke to the exhaust fumes, you will be asked to step out back by the dumpsters.

I truly hate The Wellness State and rejoice in its current financial woes. I hope they end in a total financial collapse which sends the people who do most of the real work in California back to Mexico.

What a difference on the drive back, though, when you finally see the preposterous casinos of Primm rising out of the desert and know that you are within an hour of Silly Town, where the streets are wide, parking is always easy and free, smokers are welcomed and the phrase “last call” is never heard. It's as though there were a border between Saudi Arabia and the Old Weird America, and you're about to cross it, heading in the right direction.

Another of Paul Zahl's discoveries on his recent trip to Paducah, Kentucky:

This shows the ancient, circa 1928, and original neon sign (from which the neon tubing has been removed) advertising

the Irvin S. Cobb Hotel in downtown Paducah. It is the man himself in

mid-career silhouette.

The Hotel, now apartments, is holding on for

dear life. It is apparently for sale, has no immediate buyer, yet

preserves a perfect Art-Deco lobby designed by the same firm that

created the famous Peabody Hotel in Memphis. There are several Art-Deco wood sculptures in the lobby, an amazing original dining room, now

darkened and filled with junk; and a painted ceiling that calls to mind

the St. Regis Hotel in New York. This was also the tallest building in

Paducah, once upon a time, since Cobb was its most renowned favorite son. Yet who

reads him today? And where dwell the ghosts of past guests at this Twilight Zone sort of a place?

I love the sign, and I love the place.

Mattie Ross, the protagonist and narrator of Charles Portis's 1968 novel True Grit, originally serialized in The Saturday Evening Post, is one of the great voices in American literature — one that can stand with the voices of Ishmael, Walt Whitman, Huckleberry Finn and Bob Dylan.

Mattie embodies the contradictions and the mystery of the American character as no other figure in our literature does, quite. How is it that a people so hard-working, tightfisted, materialistic, imbued so deeply with a fun-killing Puritan ethic, nevertheless manages to create characters and legends of such wildness, such free-spirited exuberance, such eccentric moral beauty? There is no answer to that question, ultimately, no way of resolving the contradictions, explaining the mystery. All we can do is observe it, as we observe Mattie, and marvel.

Mattie is 14 when her father is murdered and his murderer flees into the ungoverned Indian Territory of Oklahoma. She hires a hard-bitten U. S. Marshall with a vicious side to go bring the fugitive back, and she determines to go along on the trek to make sure the job gets done. Mattie is a ruthless bargainer in the negotiation, cold-blooded in her determination to see her father's murderer dead — hung by the law, if possible, but dead one way or the other, by any means necessary.

In this she is driven by the ethos of the Old rather than the New Testament — and she is a dogmatically religious person — but her passion is actually more personal than dogmatic. She does not seem to mourn her father, or show a lot of sentiment over losing him — but this is a misdirection. Vengeance is her way of mourning, heroic effort is her way of showing love — and on this unspoken truth the novel turns. For she has found in the man she hires, Rooster Cogburn, a person exactly like her — a seemingly cold tracker and killer of men who has no other way of expressing his values, his profound if often misdirected decency, than by acting as an agent of the law.

In the miracle of finding each other, however, the cold abstraction of the law is overturned. Cogburn becomes a surrogate father, one who will not leave Mattie, either by getting killed or by dereliction of duty. She becomes a surrogate daughter, someone he can love by protecting. They are both redeemed by their love for each other, and the climax of the novel is not the final confrontation with the murderer, but Cogburn's super-human race to save her life.

They remain tragic figures — redemption is not the same thing as satisfaction, as happiness. They have met each other by chance in the only situation in this world in which either of them could truly love another person. But it's enough — more than enough. On their remarkable adventure, they live intensely enough to last a lifetime. They create a story together that transcends their own personal limits as human beings, just as it transcends time. In telling this story, Portis adds another episode of paradoxical grandeur to the American legend.

The novel was of course made into a famous film starring John Wayne, in 1969, which has now been remade by the Coen brothers, who reportedly have stayed more faithful to the book. The new film will be released on Christmas Day this year. My guess is that it will be a blessing to our culture, if only by steering people back to a magically profound novel.

On his recent trip to Paducah, Kentucky, Paul Zahl found an empty palace of dreams:

Of the two surviving movie palaces in Paducah, The Columbia is the larger and more ornate. I saw heavy demolition equipment in

the rear and got worried. Fortunately, I was able to consult with a

professor of regional history who knows all about

Irvin S. Cobb and more about Paducah as a riverfront city. Dr. Robertson said

that The Columbia is not slated for demolition, although it is

derelict. Cobb's movies, such as Steamboat Round the Bend and the

one he made after Will Rogers was killed — in which the studio tried,

unsuccessfully, to make Cobb into Rogers's folksy successor on screen —

would have been shown here. This theater is only six blocks from the

confluence of the Tennessee and Ohio Rivers.

Harry Rossi directs his first Majestic Micro Movie — watch it here:

Breathless Remake

Another report by Paul Zahl from his recent trip to the area around Paducah, Kentucky:

This is one of the main avenues of the ancient Oak Grove Cemetery in

Paducah. Here Irvin S. Cobb is buried, here is where John Ford came in

1961, while shooting his section of How the West Was Won nearby, to pay his respects to his old friend, and here is where the prototype for Cobb's (and Ford's) “Judge

Priest” (i.e. Judge William S. Bishop) is buried, right beside Silent Avenue.

This is Cobb's grave in Oak Grove Cemetery:

The inscription

reads, “Back Home”. A dogwood tree, as per his dying request, shades the

grave. He wanted only the Twenty-Third Psalm read at the grave,

together with the choir of a local African-American congregation to

sing “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” and “Deep River”. Cobb's wishes were

honored.

Mercy Avenue is another of the main axes of Oak Grove Cemetery. I

got up high on some crumbling steps leading into a mausoleum in order

to get this one. I think if we could all spend some time on “Silent

Avenue” and then perhaps forever on “Mercy Avenue”, we would be in

excellent shape.

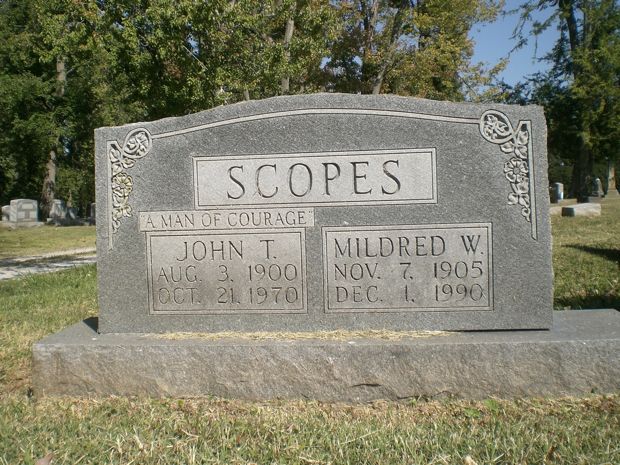

Just a few “blocks” down Silent Ave from Cobb's grave is this one — the grave of John Scopes, the

teacher of evolution in the Tennessee public schools who was prosecuted

in the famous “Monkey Trial” of 1925:

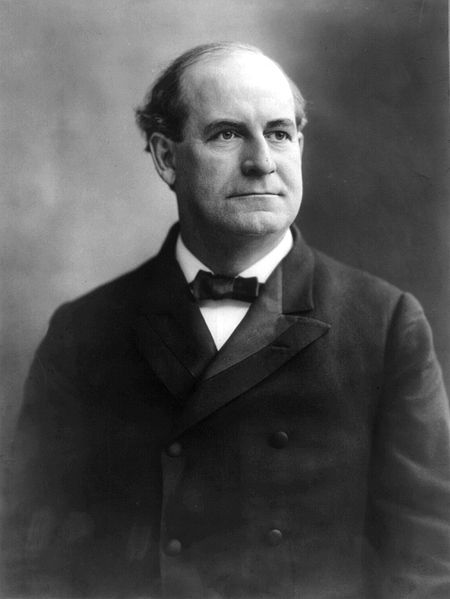

This is the man whom Clarence Darrow (or

Spencer Tracy, for those of you who remember the movie about the trial, Inherit the Wind) defended, and who won, after a fashion. He was found formally guilty and

fined $100, but the judgment was regarded by everyone at the time as a

victory for free speech, and even evolution itself. In the film, Frederick March played William Jennings

Bryan (below), who stumbled in attacking this man, and never fully recovered from

the moral defeat which the trial was for him.

What a picture of

Twentieth Century America, in one acre of ground — Cobb, now no longer

famous, with a big grave near the entrance; his prototype for “Judge

Priest” buried nearby, on Mercy Avenue, a man who kept on getting elected

because the Confederate veterans of the county were “Yellow Dog”

Democrats — that is, people who would vote for a yellow dog before they would vote for Republican; and then, after all that, down the way, the simple memorial

to John Scopes, “A Man of Courage”.

Contrary to the opinion of some — including Barack Obama, apparently — independent voters are not attracted to “safe”, middle-of-the road candidates. They are attracted to candidates who can convey passion and vision in an appealing way. This is why independents voted overwhelmingly for Ronald Reagan — and also for Barack Obama. These men offered strikingly different visions of America and how its government should work, but both made people feel good about America, made them feel that America belonged to them, and to the future.

Retreating from the vision he conveyed so powerfully during his campaign, trying to govern from a wishy-washy middle, with no discernible passion or convictions, Obama has totally lost independent voters and much of his base. He is taking down the Democratic Party with him. Meanwhile, the Tea Partiers, with an excess of passion, though a somewhat wobbly vision, are attracting the independents who put Obama into office. The Tea Party has no coherent or rational program, but it has stolen the narrative that Obama won with — this country belongs to us, it's broken and we can fix it.

That the Tea Party can have had such success without a program is evidence that the nation is ready for a third party. A third party of genuine vision, with the passion of the Tea Party but eschewing its uglier and nuttier aspects, could change the face of American politics.

Fully one half of American citizens today between the ages of 19 and 29 identify themselves as independents — they have no loyalty to either of the major parties. That percentage is not likely to fall in the years ahead, given the current unattractiveness of the major parties, and new generations coming of voting age will likely swell their ranks decisively. (Within five years, millennials will represent one third of the electorate.) This means that one major barrier to the success of a third party, the inertia of trans-generational party loyalty, is crumbling before our eyes.

The extremism of the Tea Party fringe is creating quiet but real unease among moderate Republicans, and the Democratic Party's outright betrayal of its progressive base is creating divisions on the left that are becoming increasingly bitter.

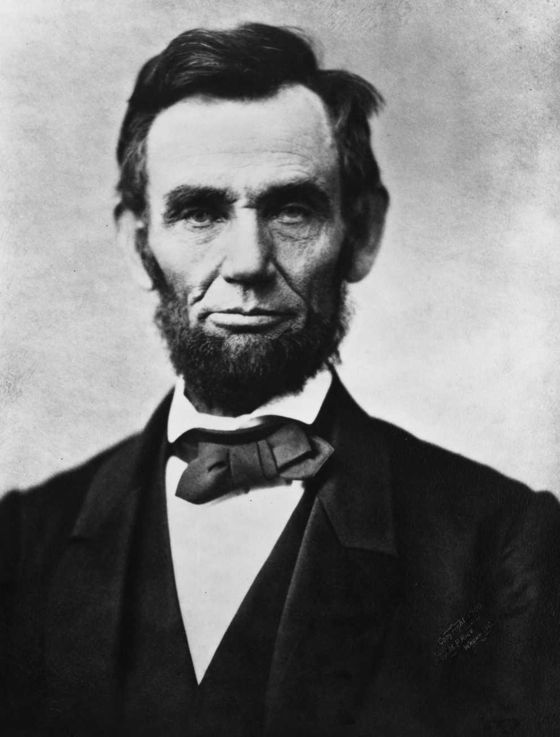

These are the kinds of conditions that have given birth to successful and near-successful third parties in America's past. The withering of the Whig Party and the divisions in the Democratic Party opened a way for the Republican Party in 1854. The Republicans, with their passion and vision, put their candidate, Abraham Lincoln, into the Presidency in 1860, just six years after the party was founded.

In 1912, when the former Republican President Teddy Roosevelt felt that the current Republican President Taft had betrayed the progressive ideals of the Republican Party, TR founded the American Progressive Party, popularly called the Bull Moose Party, during the election year, and it actually outpolled the Republican Party in the elections. There's no telling what success TR might have had if he'd founded his party even a year earlier.

This is one reason for progressives to stop rewarding Democrats for their failure and cowardice and to start looking for an alternative immediately. With the failure of TR's third party in 1912, common-sense trust-busting progressivism would never again be a significant force on the American right. If the anti-slavery activists of 1854 had decided to stick with the foundering Whig Party for just a few more years, hoping it would come to its senses, there might never have been a President Abraham Lincoln. There is a tide in the affairs of men . . .

The first tenet of TR's Progressive Party was this — “To destroy this invisible Government,

to dissolve the unholy alliance between corrupt business and corrupt

politics is the first task of the statesmanship of the day.” This is a philosophy directly relevant to the crisis of our own times, a crisis in which the survival of our democracy, under assault from the organized monied interests, the “trusts”, as TR would have called them, is at stake. It's a philosophy that, properly framed by a charismatic leader, could draw support from the baffled but passionate Tea Partiers and from the disenchanted Democratic base. Most importantly, it could appeal powerfully to the young, independent voters whose numbers are swelling rapidly.

The time has come.

Paul Zahl's thoughts on the episode of How the West Was Won directed by John Ford (a few spoilers here), with some photographs he took recently of the filming locations:

JOHN FORD'S “CIVIL WAR”

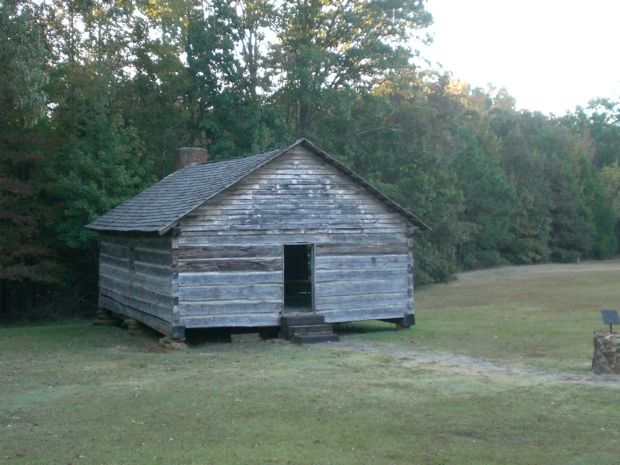

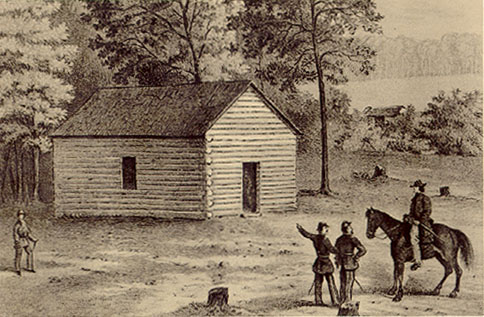

Ford also depicts the battlefield surgical station, as well as the tiny Shiloh Church — above, as it is today. This is where the fighting reached its apogee on the first day of the battle. It is a reconstruction (but on the exact site) of Shiloh

Methodist Church, which was destroyed during the battle. It is

depicted at the top of the frame at the beginning of the nighttime

section of Ford's Shiloh sequence.

They weren't able to

have church that Sunday morning April 6, 1862 . . . but . . . the day I was

there, a couple of weeks ago, I went into the current United Methodist

Church of Shiloh, which is the active church, located to the right of what you

see in the photograph, and peered through its glass doors. Behold!: a

dead woman was there. There had been a “viewing” the night before, and

there, right below the altar, in an open casket surrounded by bouquets

of flowers and waiting for a late morning church service, was a

peaceful person of middle years, lying in death, for all to see. It

was as if the entire scene were crying, “This is not abstract, what you

are seeing. It's not re-enactment time. These things really

happened. And they still do.”

Ford's Shiloh sequence feels “staged” to me, and I've felt

this ever since the days when Lloyd Fonvielle and I saw this movie in

its first run at the Uptown Theater on Connecticut Avenue, not so many

blocks from the Obama White House.

[See my thoughts on the rest of the film here.]