With thanks to Amy Crehore at Little Hokum Rag . . .

With thanks to Amy Crehore at Little Hokum Rag . . .

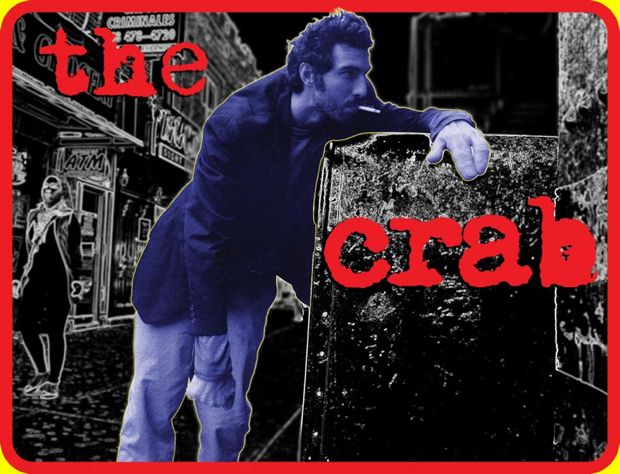

A strange, dark, oddly moving film co-produced by my friend Craig Schober, collaborator on the Majestic Micro Movies.

Check out the web site here:

The Crab

And the trailer here:

The Crab Trailer

Work Interrupted

Breaking Home Ties, cover, The Saturday Evening Post, 1954.

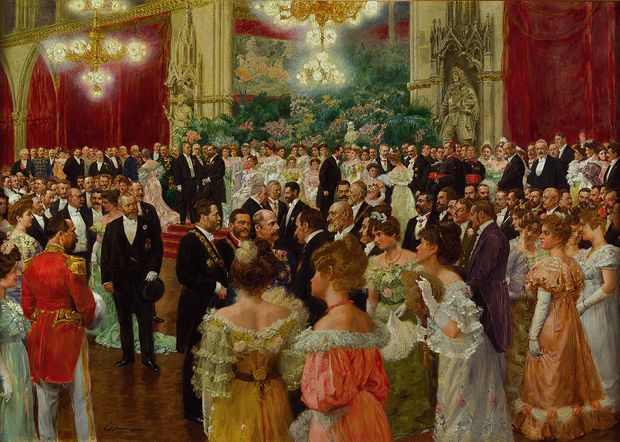

The Golden Age of Vienna, the decades just before the Great War, remains a potent image for the modern world. Everything was splendid in the Austrian capital then, and everything was rotten. Everyone seemed to know that it was all about to come crashing down in horror. This produced two responses from artists and thinkers — a deep penetration into the pathology of the modern world, and a sort of prospective nostalgia for the sweetness of what was gay in the present . . . a presentiment of what the world would be like when it was gone.

The pathology of Vienna in that era remains — this sneaking suspicion that our culture is rotten at its heart, that all its supposed splendors are trash. The gaiety is gone — replaced with a manic consumption of things and experiences, each act of which devalues the currency further. Beauty, sex, love don't even look real anymore, even from a distance, however skillfully the lighting is arranged.

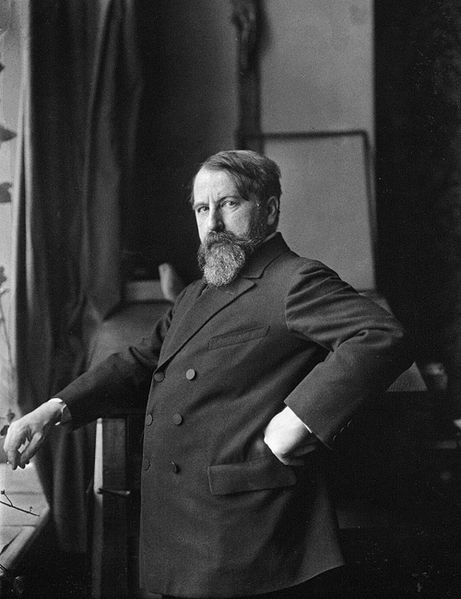

The Viennese playwright and novelist Arthur Schnitzler (above) combined a bit of both reactions in his art, though it was mostly diagnostic. Schnitzler was a doctor, and had a cold side, partly professional and partly perhaps the result of wanting to insulate himself from emotional infection by his patients. In respect to his work, we are the patients, receiving the worst news a doctor can give, and though he gives it with great elegance, he gives it straight — he doesn't mince words.

Movies have been based on Schnitzler's work since the silent era. Max Ophuls filmed two of his plays. The last film Stanley Kubrick made, Eyes Wide Shut (above), was based on a Schnitzler novel. Of course, all of these adaptations, except perhaps for Kubrick's, have been either Bowdlerized or softened in some way. Schnitzler is hard to take straight.

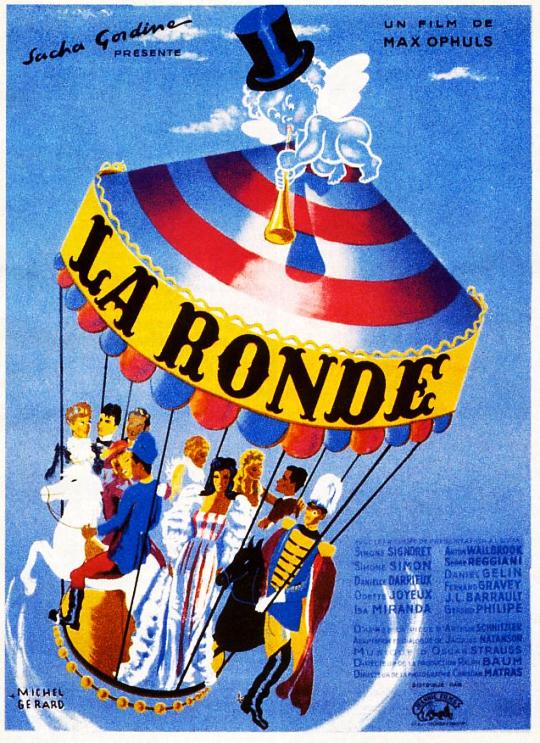

Ophuls's 1950 film La Ronde, based on Schnitzler's play Reigen, is softened only a little. We still have the merry-go-round of sexual encounters, all basically sad, all tending to demolish both romantic dreams and the various social pieties about love and marriage. But in the extraordinary final episode of Ophuls's film, the director allows us to believe that in the most degraded acts of sexual intercourse there is a tiny trace of human exchange that is redemptive — or might be redemptive, if the participants could credit it.

The feckless count in that sequence, struggling to remember a drunken night of love, is bewildered by what he feels for the whore he wakes up with. The whore, with her sweet acceptance of his confusion, offers a kind of benediction. There's a grace present in their exchange which doesn't quite seem to point the way to anything — but it's something, a little something, and it's very moving.

I'm not sure that that little something is still with us, in the utterly degraded culture of the present day — but perhaps a trace of it remains, like the lingering scent of flowers from a corsage lost in a ballroom where brilliant waltzes were danced.

It's amazing what you can do with a camera and a woman's face. It's a wonder anyone ever bothers filming anything else.

— Ron Salvatore

. . . the two and only — by Drew Freidman, the one and only.

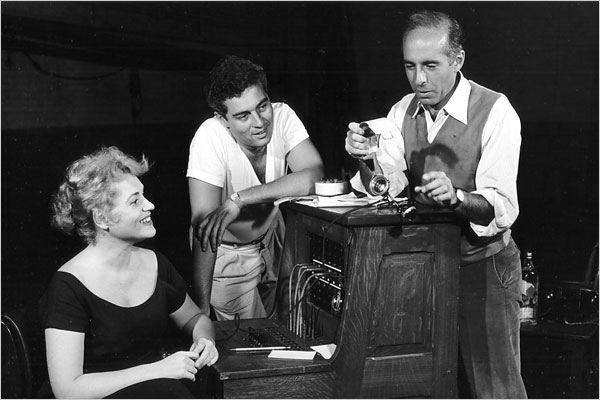

Found on the original cast recording of Bells Are Ringing, this is one of the loveliest ballads ever written for a Broadway musical. The fact that Judy Holliday and Sydney Chaplin had to strain a bit to hit their notes only adds to the poignancy of their performances. Unaccountably, and to me disastrously, the song was left out of the movie version of the show.

Above, Holliday and Chaplin with director Jerome Robbins during rehearsals.

Facebook friend Ray Sawhill once posed a “Question For the Day”:

“The work of which filmmaker(s) says ‘This is pointing the way to the future of cinema!’ to you?”

I say:

Movies will be saved, and find a future, through a renaissance that

will work pretty much the way the Italian Renaissance worked, looking

backwards and “creatively misreading” what’s seen there. No one

currently looking ahead for “the next new thing” (after Gothic

sculpture, as it were) will see it coming or be part of it.

So to answer the question in brief — John Ford.

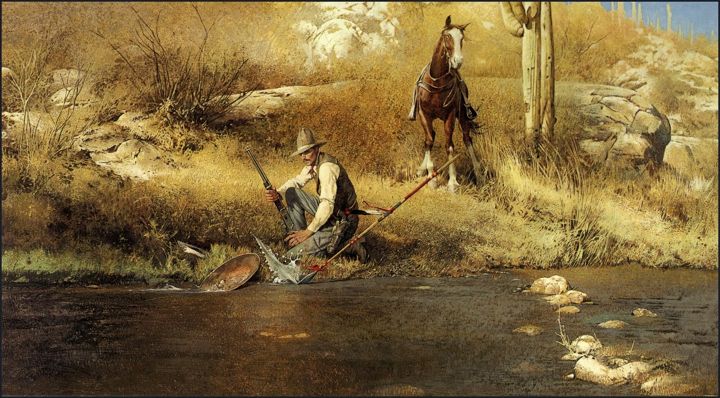

Gold Dust — with thanks to Golden Age Comic Book Stories . . .

[Warning — some plot spoilers below.]

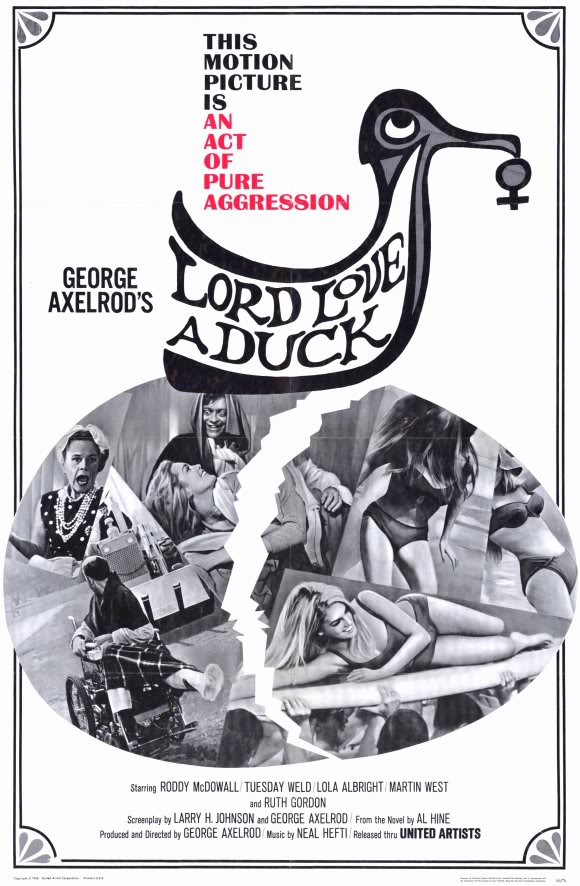

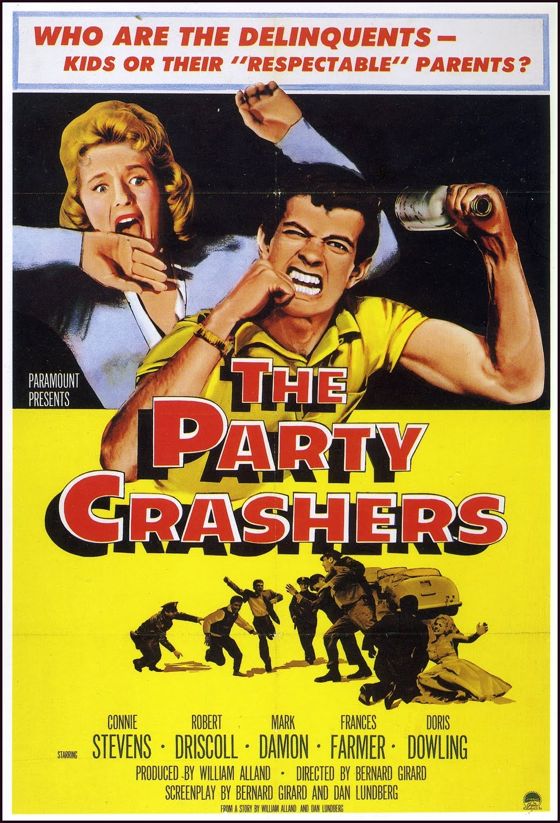

The peculiar brand of cinematic lunacy that started when Frank Tashlin and Jerry Lewis teamed up in the Fifties reached a kind of apotheosis in George Axelrod's Lord Love A Duck, from 1965. Audiences of the time recoiled from the film, and in a way it brought that particular comic tradition to an end. It was only partly Axelrod's fault.

Tashlin and Lewis, together and separately, found a way of making self-reflexive movies — movies that called attention to themselves as movies — which embodied an extreme critique of popular culture, satirizing the taste of the very audience which supported their films. They got away with it because the films were very funny, because audiences of the time clearly shared on some level the filmmaker's distrust of their own culture, and because those audiences didn't resent films which mocked them as long as the filmmakers mocked themselves in the process.

Perhaps most importantly, it was clear that Tashlin and Lewis had an appreciation, even love, for the culture they were deconstructing — they weren't standing outside and above it, pronouncing judgment.

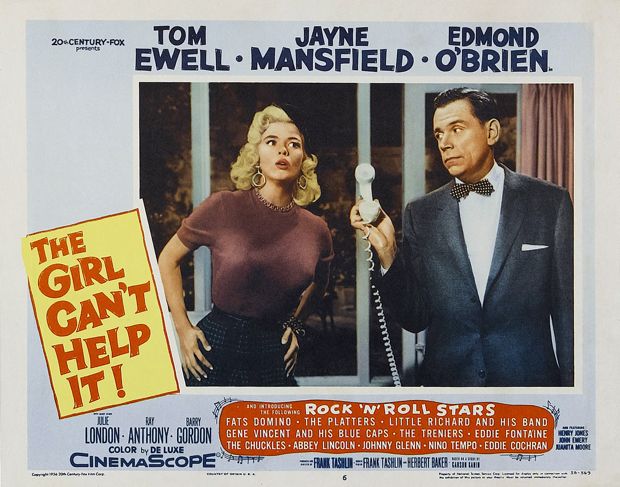

In Lord Love A Duck, though, as in Billy Wilder's Kiss Me, Stupid, the savagery of the critique, the revulsion of the filmmakers for the society they were satirizing, got too raw. The collapse of the post-WWII American male had been treated almost affectionately in Axelrod's script for Wilder's The Seven Year Itch, co-adapted with Wilder from Axelrod's Broadway play — just as it was in Tashlin's The Girl Can't Help It.

In Lord Love A Duck, as in Kiss Me, Stupid, that affection has evaporated and been replaced with disgust. In Kiss Me, Stupid there is still affection for the good-hearted women who must deal with the collapsed male protagonists, but the dizzy dame who drives men mad in Lord Love A Duck, played by Tuesday Weld, gets only a bit of pity in passing. The satire has gotten too close to the bone, and offers more frissons than laughs.

Axelrod goes for the jugular very directly in his film. The absent father in Tuesday Weld's life has become a barely human caricature of the guilty parent, with a false camaraderie which quickly escalates into babbling oedipal hysteria. Weld's mother, the abandoned wife, mocked for what she has to do to support her child, kills herself. The portrait of the father is still within the realm of comedy, of a very savage and disturbing kind — but the portrait of the mother is sickeningly sad.

Roddy MacDowell, as the magic nerd who makes all of Weld's dreams come true but hasn't got the male authority to win her love, becomes a mass murderer. Weld herself is not the sweet bombshell Monroe played in The Seven Year Itch, nor the corrupted girl next door MacLaine played in The Apartment. Weld is a bundle of empty desires, destined to be used and discarded by the men she uses.

As I suggested in an earlier note on Kiss Me, Stupid, when the critics of male insecurity start to hate women for putting up with it, the possibilities for comedy have been exhausted.

The magic nerd that Axelrod created in Lord Love A Duck would be resurrected, more benignly, in later high-school comedies like Ferris Bueller's Day Off and Napoleon Dynamite. The Coen brothers would find a new way of making savage fun of 60s middle-class culture in A Serious Man, which somehow manages to portray the same moral desolation and social absurdity without the corrosive and alienating resentment.

Lord Love A Duck stands today as a powerfully resonant film, whose creator has arrived at a kind of cultural crossroads and is paralyzed by his inability to decide which direction to take to bring his vision home. It's a crossroads which has become for him, and for a certain tradition of American comedy, a total dead end.

The horror. The horror.

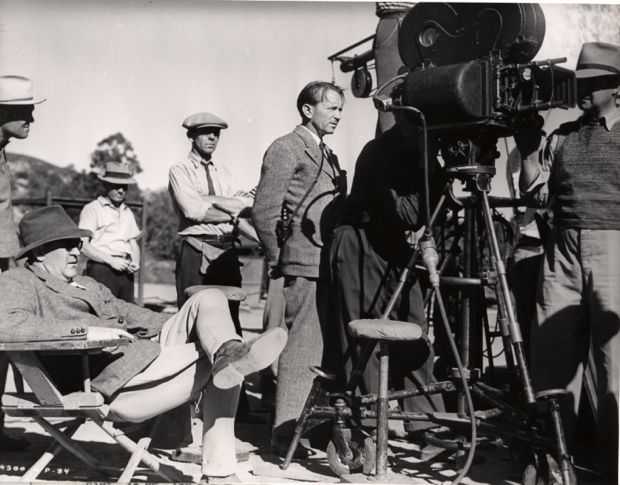

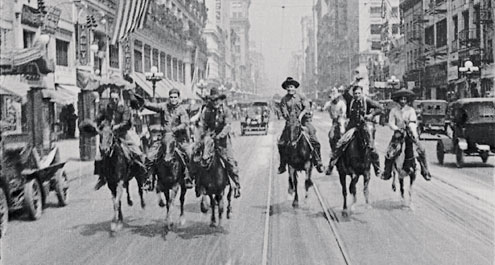

Bucking Broadway, a John Ford silent Western from 1917, is included as an extra on the new Criterion DVD edition of Stagecoach. It's a real revelation.

One of the earliest films Ford directed, it has a rather lame plot. A cowboy in Wyoming loses his girl to a visiting Easterner, who takes her back to New York to marry her. The girl has second thoughts about the guy and sends for the cowboy, who shows up in New York with some of his cowboy pals to rescue her and thrash the Easterner, who turns out to be a drunk, a lout and a creep.

The New York sequences were shot in Los Angeles, so Ford doesn't get to have much fun visually with the idea of cowboys on Broadway. Most of the city action takes place in a big hotel, and the donnybrook between the cowboys and the swells at a big society party there is clumsily staged and unsatisfying. There are a few iconic shots of the cowboys riding horses down the middle of a city street, but there's no more action than this in the urban exteriors.

It's the first half of the film, before the scene switches to the city, that offers the revelation. It's made up of a series of stunningly beautiful images of ranch life, dynamically composed shots that have real poetic power. Even back then, when Ford was just getting started, he had an eye for cinematic composition, for the choreography of movement within a frame that rivaled Griffith's. One could even make a case that his eye surpassed Griffith's by then, just a year after the master directed Intolerance.

Certainly the first half of Bucking Broadway is one of the great achievements of silent cinema, visually speaking. It transforms a simpleminded tale into a lyric poem about the West as lovely as any passage in any film Ford ever made.