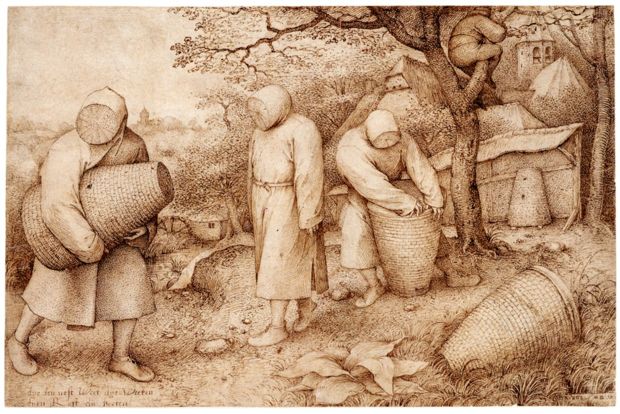

Beekeepers — with thanks to Amy Crehore . . .

Beekeepers — with thanks to Amy Crehore . . .

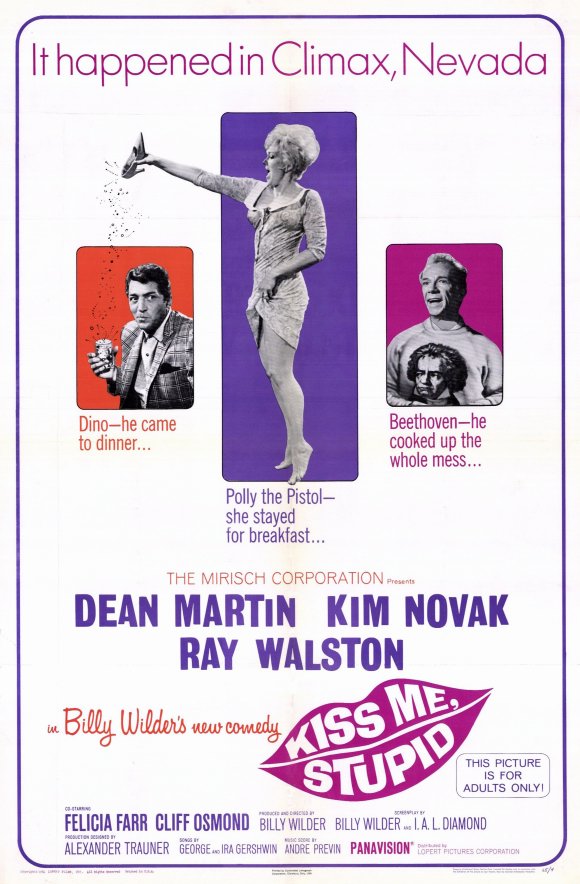

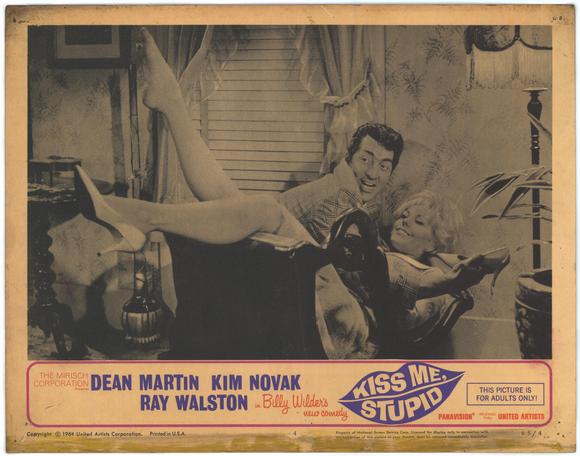

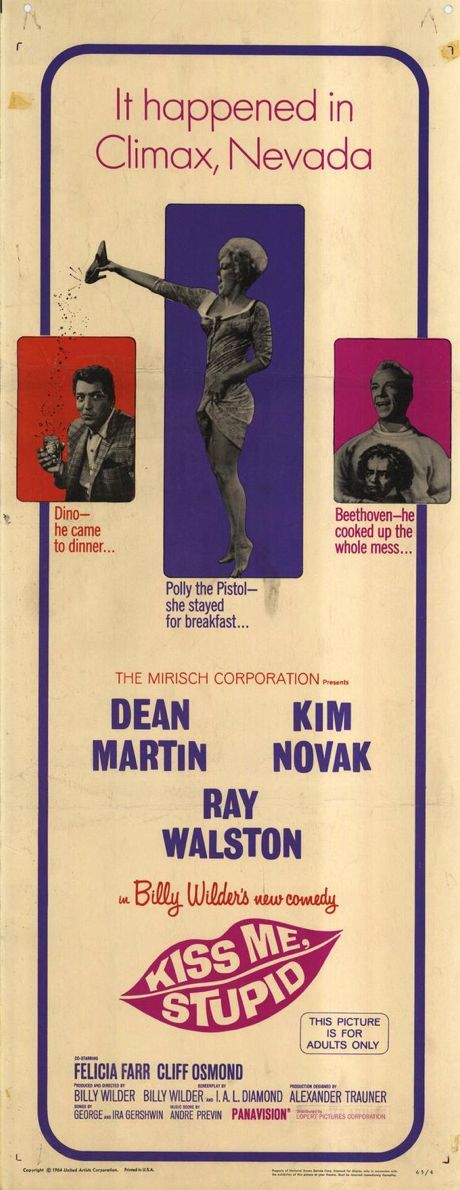

Prompted by Tom Sutpen's insightful thoughts about Kiss Me, Stupid, posted at Illusion Travels By Streetcar, I finally watched this 1964 film by Billy Wilder. Posing as a sex farce, the movie is actually a poisoned-pen letter to the American male — full of bitterness and bile.

As Tom pointed out, Wilder's great sex comedies, like The Apartment, poke fun at the puerile obsessions of American males, but also offer humane female characters who forgive them and to a degree redeem them. The dynamic is at work in Wilder's darker dramas, too, like Double Indemnity and Sunset Boulevard, but the women don't forgive in those films and the men are not redeemed — they are simply released by death.

There is bitterness and bile directed towards weak, collapsed males in all these films — it's just a question of what, if anything, balances the equation.

Kiss Me, Stupid is unique in that the equation is hardly balanced at all, and in only the most perfunctory way — and yet it is, nominally, a comedy. “Kiss Me, Stupid” might serve as the title for most Wilder films about collapsed males. Its frankness as the actual title of this one seems to reflect Wilder's inability to restrain his contempt for the modern male to any degree at all.

The film opens with a nightclub performance in Las Vegas by “Dino”, played by Dean Martin, parodying — or incarnating, depending on your point of view — his stage persona as a horny, alcoholic hipster. He delivers some patter about the showgirls in the act — cheap sexual innuendo masquerading as humor. The waiters looking on laugh like jackasses at the prurient jokes — the exaggeration of their stupidity is disturbing, totally undercutting the “glamor” of the show and the venue.

It's a kind of set-up for the rest of the film — suggesting that anyone who finds it funny is an imbecile. Wilder has moved from despising the American male to despising his audience. It's a radical act — perhaps not entirely conscious. Kiss Me, Stupid is a film that seems to be powered on some level by a hatred that's gotten out of control.

The women in the film are decent, sensible human beings — like Miss Kubelick in The Apartment. They offer a running commentary on the brutish imbecility of the men. But for once Wilder doesn't give us any avenue leading towards sympathy with the men. “Dino” remains a cartoon boor. The doltish protagonist is played by Ray Walston, who lacks the charm of a Lemmon or a Ewell, which took the edge off of their stupidity in The Apartment and The Seven Year Itch, respectively.

Kiss Me, Stupid ends with the Walston character “humanized” by his encounter with a good-hearted prostitute called Polly the Pistol, played by Kim Novak, but the change isn't convincing — it plays like a sop to audience expectations that comes too late, unfelt and under-dramatized. You sort of hate his wife for settling for a dimwit like him, even if she's found a way to manipulate him into being an acceptable mate.

The film is commonly regarded as an unpleasant failure, but it fails only because Wilder didn't follow his venomous vision to its uttermost ends. But how could he — at least in what purported to be a mainstream comedy? You get a feeling in Double Indemnity that Wilder truly hates his lead couple — not for their criminality but for their bad taste, cheap banter, infantile desires. In a drama, he could resolve this hatred by killing them. In the “comic” world of Kiss Me, Stupid he has to leave his dumb males in their nihilistic hell. The barely perceptible glimmer of hope, of redemption, he felt compelled to offer them reads as a confession of artistic bafflement by Wilder.

You can't kill off every collapsed male in America, after all — but for most of Kiss Me, Stupid you get a feeling that's just what Wilder wishes he could do. He settled for humiliating and degrading them, and in the process humiliating and degrading anyone who might find their predicament amusing.

Kiss Me, Stupid is, finally, an ugly film about ugly men. Some fun, huh? Well, not exactly — but damned interesting, if only as an example of what can happen when an artist is unhinged, deranged by the very passions that, controlled and balanced, fueled his best work.

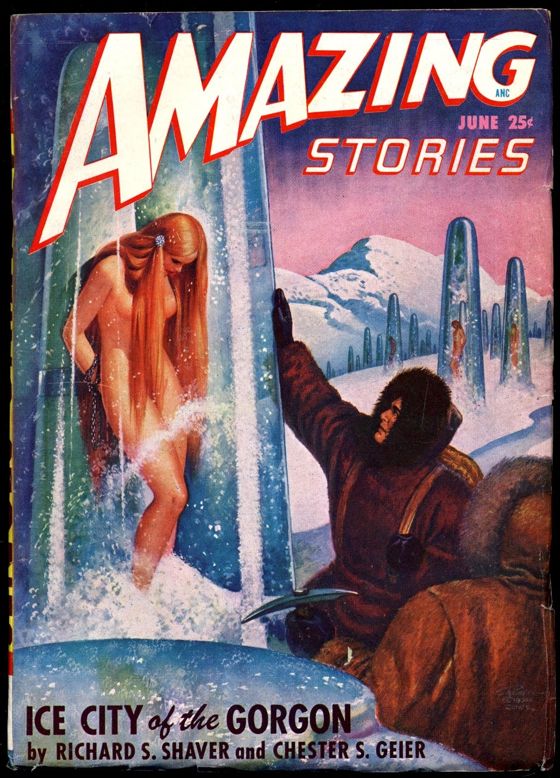

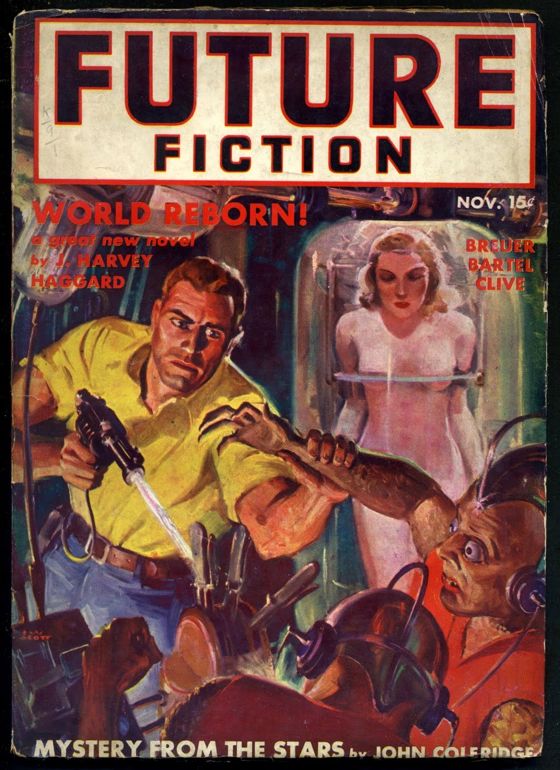

Images of women suspended vertically in transparent capsules captured the imaginations of fantasy writers in the 20th Century. Above and below, illustrations for the covers of pulp science fiction magazines.

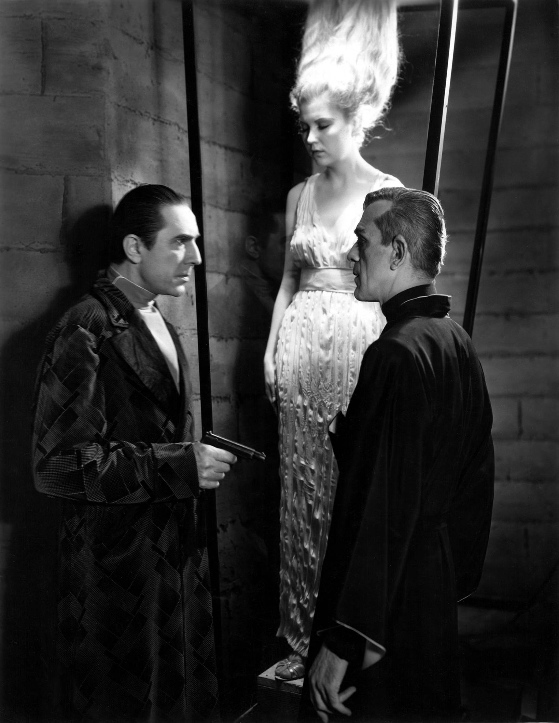

And here's the same idea in a classic Hollywood horror film, The Black Cat:

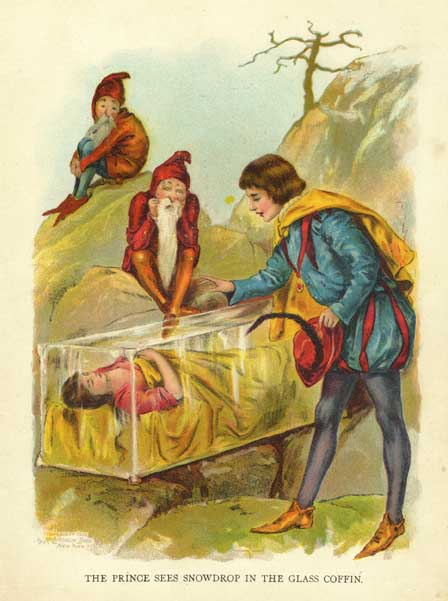

I guess it's just a variant of the glass coffin in which many a fairytale princess has slept her enchanted sleep:

Originally, I suppose, the image suggested a virginal state, from which the prince's kiss would awaken the maid, a kind of sexual initiation. I'm not sure what it signifies in the modern age, but probably not that — more likely a vision of woman as pure image or possession, safe, contained, unthreatening . . .

Imagine cinema as the sea. Imagine being picked up and hurled bodily

into that sea. Some films are like that. Suddenly, you no longer have

a picturesque ocean view, or a pleasant medium for transporting you on

a vessel from here to there. You are wet from head to toe, you are

part of the ocean, and you must swim or sink.

Greed is a film like that. The Last Laugh is a film like that.

Here are some others — Intolerance, Touch Of Evil, The

Conformist, The Searchers, Chimes At Midnight, The Rules Of the

Game, L’Atalante, Titanic, Vertigo, Seven Samurai, Sherlock, Jr., The

Band Wagon. These are not films you can just look at — you

have to navigate them, exert yourself to keep your head above

the surface of them.

I’m not talking about films which merely overwhelm the senses or the emotions (and certainly not the intellect), but films so alive with cinematic, that is to say plastic, invention that you find yourself ravished by the medium itself — aesthetically overwhelmed, as it were.

It doesn’t really matter what you think of such films, just as your opinion of the ocean is irrelevant when you’re thrown into it. You are forced to react to it, on its own terms, not yours, one way or the other. You accept those terms or you drown.

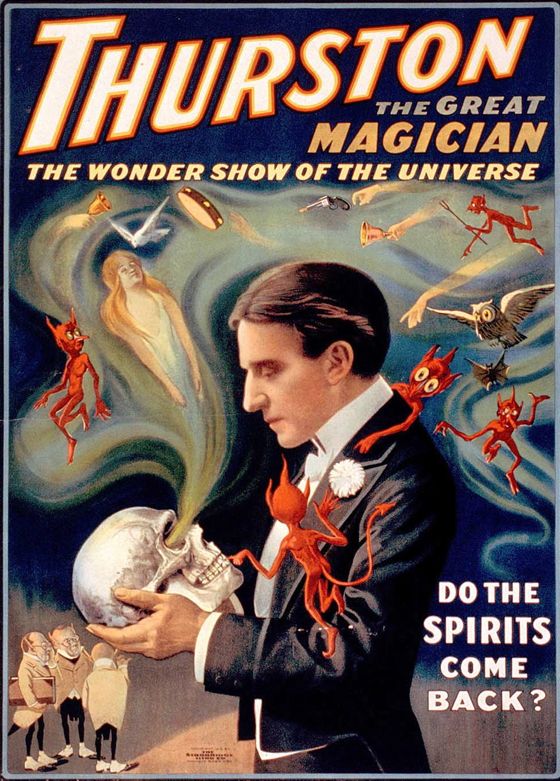

What are the chances that Thurston's answer might be no?

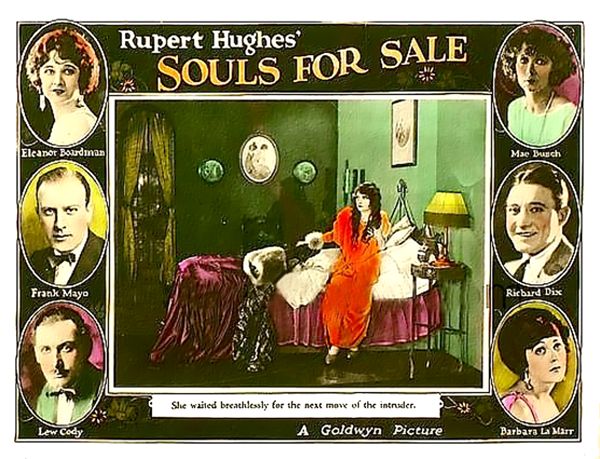

Souls For Sale is, I think, the second best movie ever made about Hollywood, and makes a perfect pendant to the best, Sunset Boulevard. Souls For Sale is a portrait of Hollywood as a kind of Eden, just as Sunset Boulevard is a portrait of Hollywood as a kind of purgatory.

The sheer, delirious joy of movie-making before the studio bean-counters took full control of the industry is present in Souls For Sale. The film tries to present a balanced view of Hollywood from the other side of the camera, but it can't really — it's too swept up in the nuttiness and energy and attractiveness of the movie folk.

The film features a lot of cameo appearances by real Hollywood stars and directors of the time. One of them is especially poignant. We get a glimpse of Erich Von Stroheim at work on a set for Greed. We know now that he was creating one of the greatest works in the history of American art, but the cameo was filmed when the production still belonged to Sam Goldwyn's company. Before Greed was completed, that company was sold to Metro and the production thus came under the control of Louis B. Mayer and Irving Thalberg, who, in an act of unspeakable thuggishness, decided to mutilate Von Stroheim's masterpiece, to send a message to the rest of Hollywood's talent — you are no longer in control here . . . the industry you built now belongs to thugs like us.

In Souls For Sale you can see what was lost in that transfer of power — the giddy excitement of a new art form still in the hands of the artists who created it — just as in Sunset Boulevard you can see the rot and decay of that erstwhile Eden under the influence of the thugs. It's no accident that Louis B. Mayer was outraged by Sunset Boulevard. It was an epitaph for everything he personally destroyed.

The giddiness of that time before the thugs took control informs every moment of Souls For Sale. It's a thoroughly self-reflexive work of art, which pretends to examine how the dream world of the movies is constructed while itself infected with the very dreams it pretends to examine. This tension in its point of view is quite deliberate and often played for laughs, though it more often results in a kind of surreal poetry.

The story opens on a train racing through the desert on its way to Los Angeles. A young bride on her wedding night has suddenly become revulsed by the man she's married and jumps off the train at a remote watering station. She wanders hopelessly through the desert until she comes upon . . . an Arab sheik on a camel, who rescues her from death. He's an actor on location with a film crew, making a movie.

So we have moved with the mad logic of a dream from melodrama to costume drama to comedy. The whole film navigates a similar dream landscape — it's a hall of mirrors from which we never emerge. At the climax, an intertitle informs us that a real hurricane is threatening to wreck the artificial storm set up for the climax of the film within the film — and we proceed to watch the “real” artificial storm ruin the “fake” artificial storm.

If Jorge Luis Borges had ever made a movie, I suspect it would bear an uncanny resemblance to Souls For Sale.

The film was based on a novel by Rupert Hughes and also directed by Hughes (who was Howard Hughes's uncle.) He was a successful playwright, novelist and historian who directed seven films between 1922 and 1924 — then went back to writing. Souls For Sale is a handsomely mounted and photographed production, with fine performances, and it has a few images of real grace and power. Hughes was either exceptionally well-supported by Goldwyn's studio technicians or else he had a genuine gift for directing. In either case, it would be interesting to know why he abandoned the craft.

He left us a minor masterpiece, though — a vision of what the movies might have been without “boy geniuses” like Irving Thalberg and “benevolent patriarchs” like Louis B. Mayer.

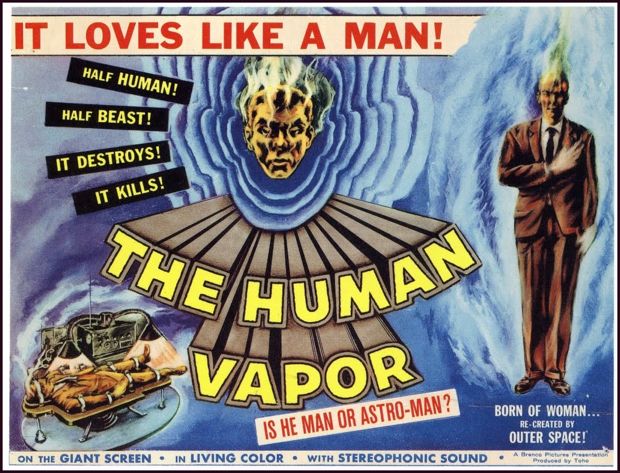

This takes existential nullity, a speciality of the exploitation movie, about as far as it can go.

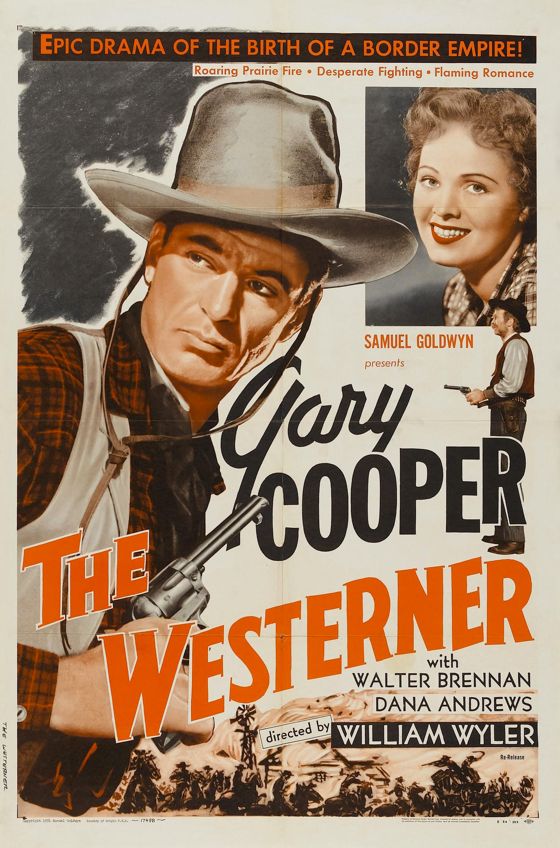

There have been A-movie Westerns ever since the silent era — that is, prestige pictures meant to appeal to a wider audience than the usual one for Westerns, which consisted mainly of kids and grown-up males outside the big urban areas. The prestige Westerns were usually epics, like The Iron House, or The Covered Wagon or The Big Trail — films whose very size and scope branded them as out of the ordinary, worthy of consideration by all.

John Ford's Stagecoach, from 1939, was something else again. Neither a routine oater nor an epic, it was instead a drama set in the Old West with an unusual and compelling story, or series of interlocking stories, and complex, well-developed characters. It was a medium-scale Western for the mainstream audience.

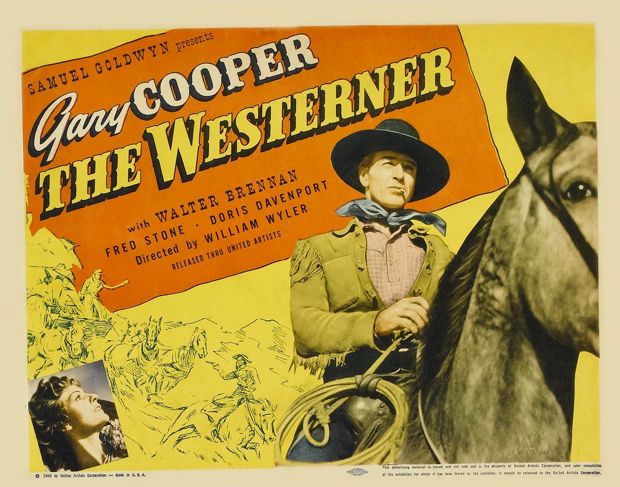

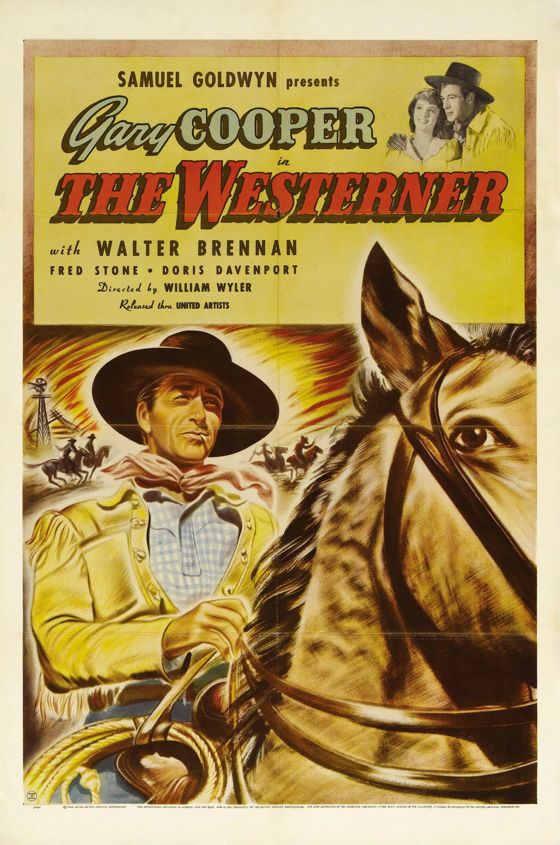

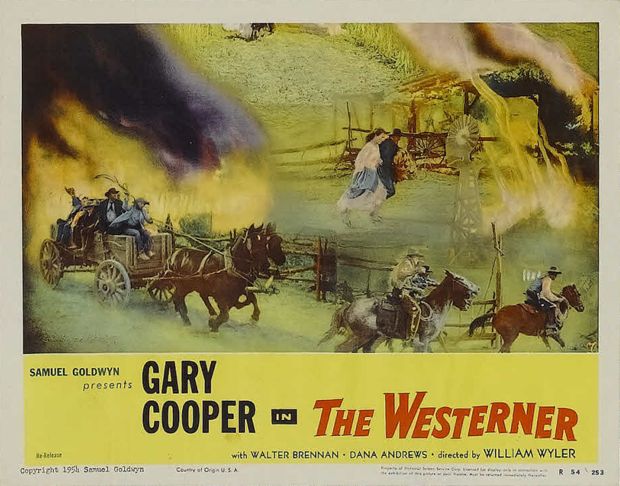

The success of Stagecoach inaugurated a new phase in John Ford's career as a director of Westerns and spawned more films like it — more medium-scale A-Movie Westerns . . . Westerns for everybody. One of the first of these to appear, just a year later, was William Wyler's The Westerner.

Wyler was a good choice to make a film in the Stagecoach mold. Like Ford, he'd earned his spurs as a director of two-reel Westerns at Universal during the silent era, so he knew the territory, and like Ford he'd moved up to more prestigious and sophisticated kinds of movies. He was thus well-equipped to tackle the more mature sort of Western that mainstream audiences seemed to want.

[Note — there are some plot spoilers below.]

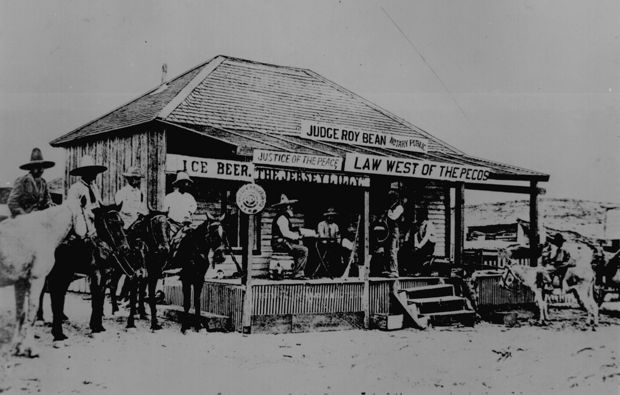

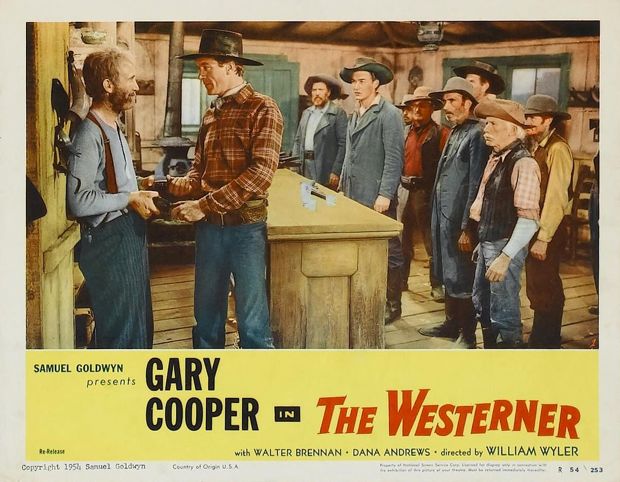

The Westerner was adapted from a story by Stuart M. Lake loosely based on the life of Judge Roy Bean, the legendary self-appointed judge in West Texas who like to call himself “the law west of the Pecos”. I've never read Lake's story, but screenwriters Jo Swerling and Niven Busch turned it into a wildly entertaining yarn about the notorious judge and a man in whom he finally meets his match, a drifter named Cole Harden. (Busch, who here collaborates on a fairly traditional, if up-scale Western, would later go on to have a strong influence on the noirish Westerns of the post-WWII era.)

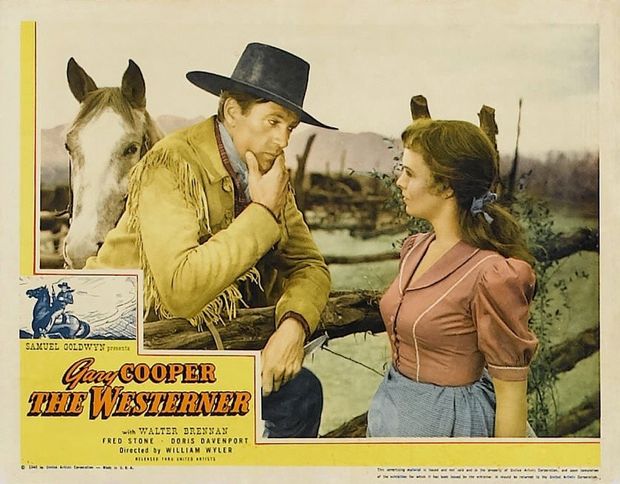

Swerling and Busch dance a fine line between serious frontier drama, pitting cattlemen and farmers against each other in a classic conflict, and colorful character exposition, with the sort of laconic, rustic humor one finds in the best of Mark Twain. Bean, played masterfully by Walter Brennan in one of his finest performances, is a truly complicated villain — vicious, ruthless, funny and touching in an almost childlike way. Harden, played by Gary Cooper, is complicated as well, with a childlike quality, too, balanced by the iconic virility of his physical person.

These two men amuse each other, delight in outwitting each other, getting the jump on each other — they were born to be the best of pals . . . until Bean's sheer cussedness and meanness prompt a showdown. There's something tragic about the inevitability of this — it has the quality of a love story gone horribly wrong.

Like Stagecoach, The Westerner has long interior scenes in which displays of character take center stage. After an action opening, the film stays put for almost half an hour in Judge Bean's combination courthouse/saloon, as Harden tries to con his way out of getting hanged for stealing a horse. It's terrifically engaging stuff, because of the actors' magical incarnation of their roles and because of the genuine homespun wit of their dialogue.

Wyler gives the traditional Western audience its thrills, too. The film has some of the most beautiful running inserts of galloping horses ever filmed — and a big part of the thrill of them is just watching Cooper ride. Cooper had worked as a cowboy and he knew how to sit a horse at a dead run with an uncanny grace few actors in the history of movies have ever matched.

The film is magnificently shot by the great Gregg Toland, and magnificently designed — with a kind of romanticized grubbiness that reminds one of the work of Frederic Remington.

There's a love interest for Cooper, of course, with one of the women of the farm community, which helps motivate his conflict with Bean, who's on the side of the cattlemen, but it doesn't ignite many sparks. Cooper's winsome shyness with the lady gets stretched pretty thin by the final clinch, until it almost seems fey.

The film does make a stab at an epic dimension, presenting the feud between the pioneer groups as an episode in the making of Texas, and the nation — something the studio drew special attention to in the advertising. There's a big set-piece sequence showing the burning of the farmers' fields and homes that seems to have been meant to evoke the burning of Atlanta from Gone With the Wind, released the previous year. But much of the fire is done with process work, and Wyler doesn't appear to have had his heart in this part of the movie. He knew that the best thing he had to work with was the relationship between Bean and Harden.

Most unusually, the final shootout between the two men takes place in an empty frontier theater. The image makes sense here, though, because the heart of the film is men telling each other tales, hoodwinking each other, competing in the playing of roles. Its a vision of the Old West as a place in which a big part of life is the theatrical presentation of the self. Bean doesn't seem at all bothered that Harden gets the better of him in the end — he's played his part as well as he could, and the curtain always has to fall sometime. He and Harden still love and admire each other — but the show's closed.

[Image © Langdon Clay]

There's always a creepy grin waiting for you at a Hampton Inn!

In Part One of this report, Paul Zahl, in pilgrimage mode, located, briefly viewed and photographed the former home of the late novelist James Gould Cozzens at the bottom of a hill outside Lambertville, New Jesrsey. Then he decided to go back up the hill in search of a man he'd been told might have some information about Cozzens during his time of residency in the area. Paul had been directed to this “man on the hill”, no fool as it turned out, quite by chance, by a woman he'd met who was out walking on the road that ran past the old Cozzens house. Here, in the pilgrim's own words, is a report of what ensued:

“A VOYAGE TO THE COUNTRY OF THE

There was a sadness incipient to

this old church building, a feeling shared by the stone cherub weeping

on the ground, just to the right of the main entrance to the church,

the entrance from which, as it were, Judge Lowe and Arthur Winner, Jr. in a scene from

Now that Spring is here, the days of bright sunshine seem to unfold

with greater authority, no longer a promise but an actual downpayment

on the summer.

The vacation motels along Thompson Avenue, with names suggesting an

intimacy with the beach (an intimacy which is betrayed in fact by the

unseen barrier of the 101 Freeway) look brighter, too — the neon

“Vacancy” signs, merely pathetic in February, now have the quality of

confidant, if insincere, smiles.

Yesterday I decided to spend one of these bright days inside a movie

theater, watching The Mod Squad — a mistake I hope others will not

make. Depressed by the spectacle of such wonderful actors mouthing such

dull-witted dialogue I came out into the late afternoon on Main Street

and my spirits were instantly restored.

The ocean peeked back at me from the end of Chestnut Street, the

slanting light made the small-scale buildings of downtown Ventura look

like toys. As I walked to my car I passed the old Ventura Theater,

where the last evening of the Monster Swing Weekend was already in

progress. The Rumba Bums were on the bill, but I heard no music, just

squeals and cheers from a crowd inside, like the innocent echo of

lighthearted evenings long past.

I had the sensation of being on a movie set, but the feeling wasn’t

alienating, because it was my movie, set on the streets of my little

town, Ventura . . . an imaginary location somewhere on the coast of

California.

If one wanted to deconstruct this film visually, the task would not be hard — it practically deconstructs itself while you're watching it.

There are six types of images in the film, all radically different from each other in terms of how they were created:

1) Location shots, with unmanipulated images, including shots inside sets built on location in which you can see the actual location outside the doors and windows:

2) Studio interiors in which you can't see outside the door and windows, and which thus don't require false exteriors:

3) Studio exteriors, with artificially constructed “natural” settings:

4) Shots of people supposedly traveling on a raft down a river filmed against backscreen projections, with the foreground raft in the studio moving on gimbals:

5) POV location images looking forward from the moving raft shot on smaller-format cameras than the ones used for the rest of the film and blown up to fill the Cinemascope screen. (These are identifiable by their strikingly different grain structure from the other shots in the film.)

6) One single shot from a location on the river with a town on the shore of the river matted optically into the frame.

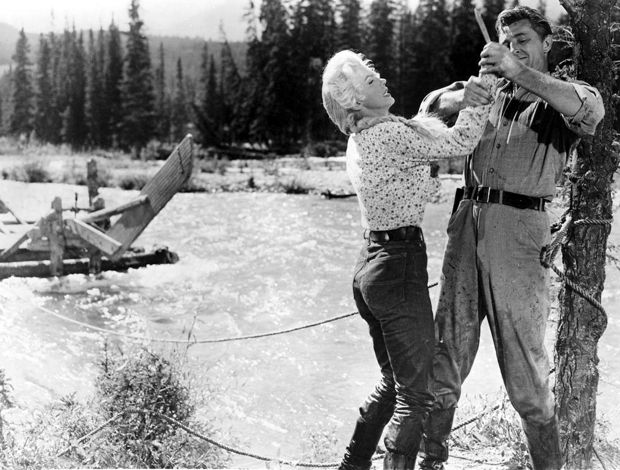

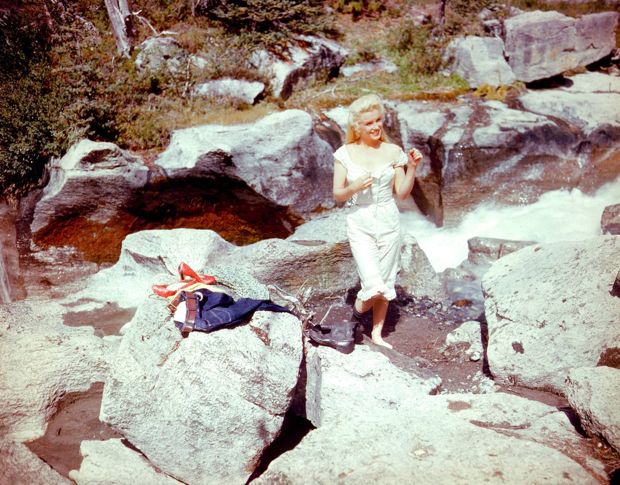

It's extraordinary that audiences of the time processed these disparate types of images as a coherent visual whole, but they clearly did. Contemporary reviewers of River Of No Return remarked on the spectacular location scenery and the exciting action scenes on the river without noting that the former were unmanipulated images and the latter tricked up in a studio.

What makes the contrasts between these disparate types of images starker than they might be is the stunning nature of the location shots. They are beautifully composed, give an impression of deep space, and often go on for considerable amounts of time in which complex and difficult actions occur on screen and which not infrequently involve elaborate camera moves.

All of these aspects of the shots made on location were characteristic of the director Otto Preminger's mature style and made him a darling of the Cahiers du Cinema set in the Fifties, influenced as it was by André Bazin's celebration of long takes and deep focus, as opposed to montage, as the primary and most potent tools of cinema.

Quite apart from theoretical considerations, Preminger's location images in River Of No Return are among the most beautiful and exhilarating in the whole history of Westerns. They are images that drawn you into the spaces of the scenes, imparting a sense of actually inhabiting them.

Robert Mitchum and Marilyn Monroe, the stars of the film, don't have a lot of screen chemistry, and Monroe delivers one of the stiffest and most awkward performances of her career, but when the two have a long magic-hour conversation by a campfire with a river rushing behind them, filmed in a single long take, performance hardly seems to matter.

The sheer cinematic beauty of the shot infuses itself into the actors, the dialogue, the narrative moment, the whole story of the film, so that we can accept these characters as people fated to become lovers, simply because they have inhabited this passage of sublime cinema. Aesthetic excitement is transmuted into emotional power. We believe that the characters will remember this moment forever, simply because we will.

Such scenes carry us through the backscreen passages, the artificial cave and the forest with the artificial trees. The latter become like dreams within the dream, and the dream of that actual fire beside an actual river at an actual sunset becomes the film's enduring reality.

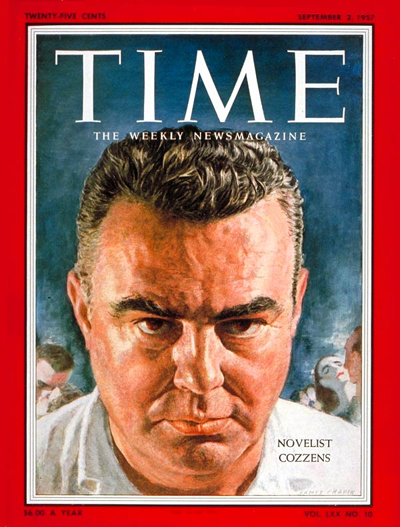

Following his passion for the work of novelist James Gould Cozzens, Paul Zahl recently made a pilgrimage to Lambertville, New Jersey, where the reclusive Cozzens lived and worked and hid out from the world. Here is the first part of Paul's report from a country he has named in honor of one of the strange lands visited by Lemuel Gulliver in his travels:

“A VOYAGE TO THE COUNTRY OF THE HOUYNHNMS” — Part One

James Gould Cozzens (1903-1978) admired Jonathan Swift beyond almost all other writers. He also agreed with Swift's view of human nature. Like Swift, though not as extreme as he, Cozzens was a misanthrope. [Swift's Gulliver, it will be remembered, preferred the Houyhnhnms, a race of intelligent horses, to any of the more human creatures whose lands he visited.] He was also a hermit.

In 1957 a Time magazine cover story called Cozzens “The Hermit of Lambertville”.

Because I like Cozzens' novels, among them By Love Possessed, Guard of

Honor, and Men and Brethren, I decided to see if I could locate the

house, outside Lambertville, New Jersey, in which the great one, who

didn't like people, wrote these books.

Because Cozzens' literary reputation took a nose dive in 1958, and has

not risen again, there is little to go on. Matthew J. Bruccoli

published the sole biography of the man in 1983, and in it there is a

photograph of the Lambertville house, known then as “Carrs Farm”, in

which Cozzens and his wife lived from 1933-1958. But I could find

nothing more — no address nor further specifics, of any kind.

Therefore, on June 12, 2010, I took the opportunity of being in

Princeton to borrow a car and drive the 40 minutes or so over to

Lambertville in search of Carrs Farm. I knew it was about three miles

outside of town, on a country lane called Goat Hill Road. Calls to the

Episcopal rector of Lambertville and to the Hunterdon Country

Historical Society had been returned but no one seemed to know anything

about Cozzens nor the 25 years the once famous writer had been living

in their community.

Or almost no one.

Early on a misty Saturday I drove the back roads from Princeton through

Lawrenceville then through more or less soft and hilly country, to the

end of Goat Hill Road. Several large houses, with spacious lawns and

well kept gardens, were hidden from the road. I did carry a photograph

of Carrs Farm, fortunately, taken from the Bruccoli biography:

But everything was too hidden away to see.

Then, behold: a nice lady taking her morning walk. I stopped the car

and asked after my man. She said, well, if you mean the fellow who

wrote a novel about World War II, I've heard he lived somewhere along

this road. I think it's the house at the bottom of the hill, on the

left. Furthermore, a half mile or so the other way, at the top of the hill, you may find a

gentleman at home who has lived here for many years and knows

everything.

And so it was! My walker was right. Right at the bottom of the hill was Carrs Farm.

When I got out of the car, I noticed that “Keep Out” and “No

Trespassing” and “Private Property” signs were pointedly posted at the

entrance to the farm. Was there a regular army of Cozzens-enthusiasts

I didn't know about, who had disturbed the peace of the current owner?

(I later found out there were other reasons for the signs.) But I

slipped in anyway, prepared to be the nice interested clergyman that I

hope I am, if an owner came upon me. The owner didn't, but the owner's

friend did, who did not know about Cozzens but warned me to get out

of there fast. I took the one photograph of the exterior, on the run; and

it sure is the house:

That's for sure. And almost completely unchanged, but for a metal rail

at the steps and the boxwoods cut differently. Cozzens himself would

not have welcomed visitors either, as he apparently lived only to write

and think, albeit happily married to his wife, a literary agent who

commuted Monday through Friday into Manhattan.

Oh, and Cozzens would write in the mornings and garden in the

afternoon. Like his characters Arthur Winner, Jr. and Arthur Winner,

Sr. in By Love Possessed, the man cultivated roses, antique roses, to

be specific, with dedication.

After breathing a sigh of relief, for one had found what one was

looking for, and had not been beaten away with brooms, I decided to walk up in the opposite direction and pay

a call on the man on the hill. He was, as it turned out, no fool.

[Click here for the second part of this report, in which our intrepid pilgrim meets the wise man on the hill, who imparts knowledge, and ventures into Lambertville itself, searching for traces of the small town its famous hermit once knew.]

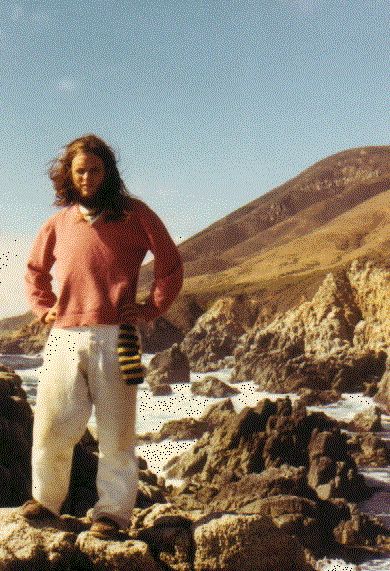

Sometimes I think about my rambling days — the late 60s and early

70s. Then, when it was a “damp, drizzly November in my soul”, I

wouldn’t, like Ishmael, sign on for a three-year whaling voyage — I’d

get a lift to the nearest Interstate, stick out my thumb, and . . . go.

I might have a vague destination in mind, or I might not. I wouldn’t

have much money on me — that’s for sure. Ten or fifteen dollars stuck

in the toe of my shoe. I just threw myself on the mercy of the world,

and chance. The world and chance never let me down.

It was madness, of course, in practical terms. God knows what might

have befallen me on such journeys. But people were infallibly kind and

generous, and interesting. The world seemed a sweeter and safer place

than it has ever seemed since — when I had more to lose.

When you’re homeless in this world, then you’re home. When you’re on

the road, you’re at journey’s end. When you’re lost, you’re found.

How many of us, in our rambling days, have known this . . . and

forgotten it?