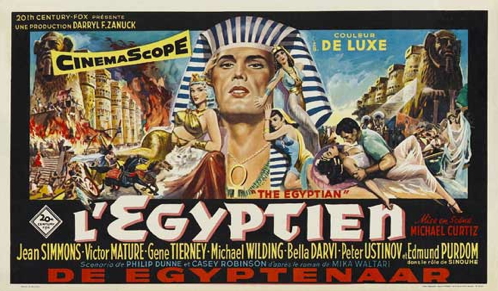

Some thoughts by Paul Zahl (of The Zahl File) on Jack Kerouac and his connection to Michael Curtiz's costume epic The Egyptian. Huh? Read on:

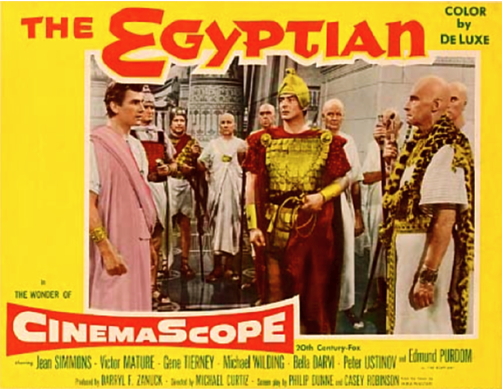

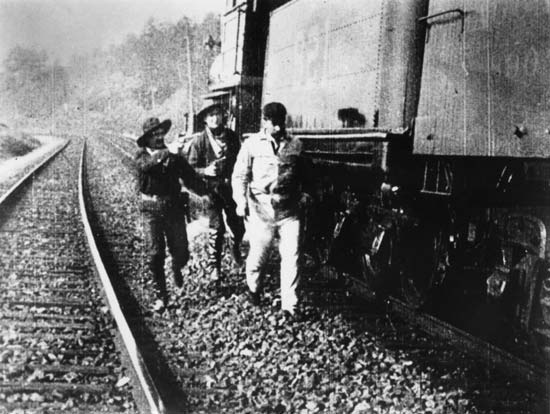

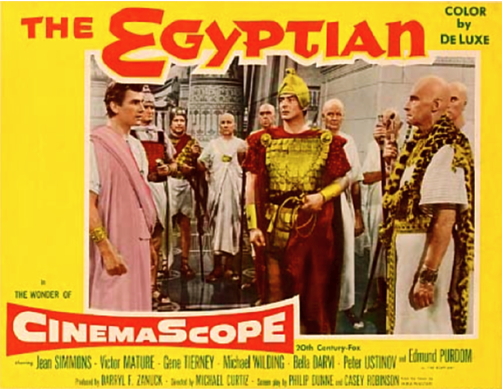

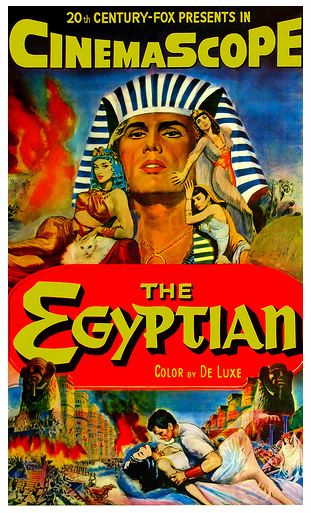

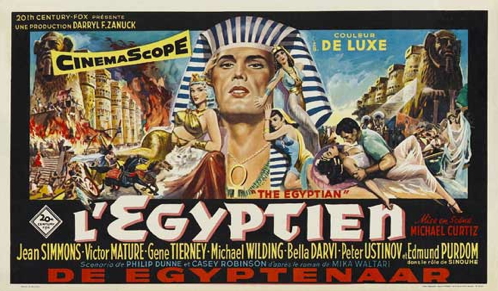

The 1954 Hollywood movie The Egyptian, a big picture, with Jean Simmons

and Michael Wilding, among many others, is hard to find — all but impossible

to find, in fact, until the days of Internet magic. (It's available on a Korean DVD.) It was produced by

Darryl F. Zanuck and directed by Michael Curtiz. Curtiz had directed

several big pictures, including Casablanca and Mildred Pierce, not to

mention The Walking Dead and Mystery of the Wax Museum.

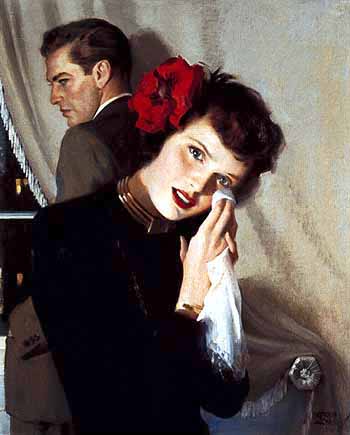

The Egyptian tells the story of a young doctor in Ancient Egypt —

meaning Thebes, Memphis, and Luxor — who is ensnared pitifully by a

temptress known as the “Woman of Babylon”, completely loses his

self-respect, together with everything he owns as well as his post as

Physician to Pharaoh, and finally recreates himself as a

healer wandering throughout the Ancient World. He prospers, only to return home

to lose his true and loyal love, played by Jean Simmons, and to become

caught up in the failed but sublime One God movement of the Pharaoh

Akhenaten. In a touching scene that works dramatically and

cinematically, Sinuhe, the doctor, is converted to monotheism. After

all his sad experience of life, Sinuhe seeks monastic solitude in the

desert, a sadder man but much wiser.

The Egyptian is pretty good. The sets are gorgeous, the camera is

fluid and assured, the acting (with the exception of Gene Tierney, who

is miscast as Pharaoh's sister) confident if a little wooden, and the

matte paintings and miniatures convincing. Personally, I like the

religion of the film, with Akhenaten's confession of his universal faith

going down well, with pathos, at the end. Some might say that The

Egyptian is suffused with '50s-style religion in this country, but that

would be unfair. The film is so anchored in the pessimistic views —

i.e., life as an exercise in dreamy futility, with loss — of the

author of the original best-selling book, that Akhenaten's “witness” in

the last scene but one, comes off as credible, and for me even

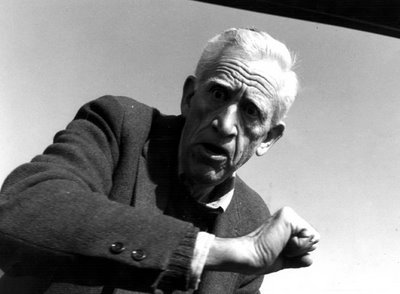

hopeful. The novel on which The Egyptian is based, incidentally, was

written in the Finnish language by Mika Waltari. In the days of our

fathers and mothers, Waltari's novel was an international sensation.

Waltari's father, incidentally, was a Finnish Lutheran pastor. It was the Finnish Lutherans, of course, who brought us The Flying Saucer Of Love.

Here's the thing:

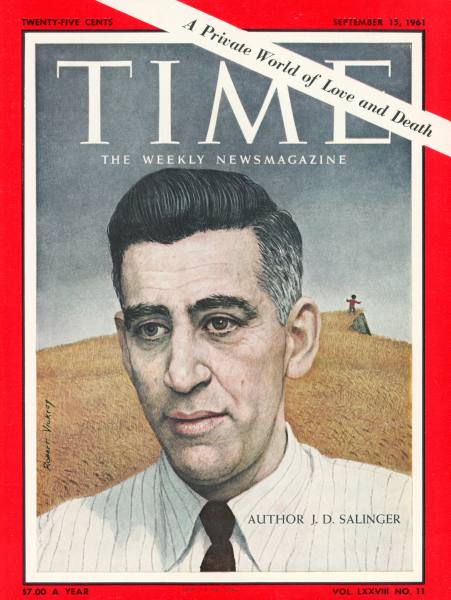

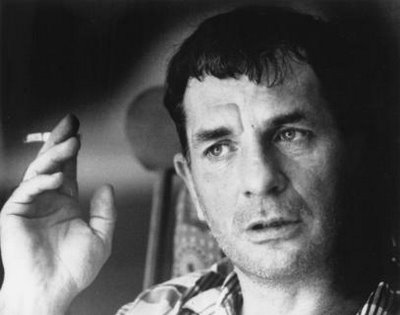

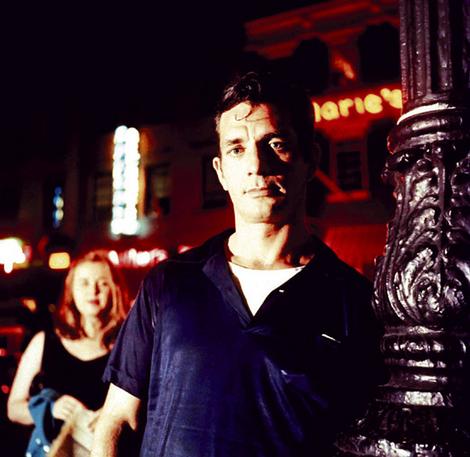

Jack Kerouac saw The Egyptian in a movie theater when it first came out.

He hated it!

The vehemence of Kerouac's response to this relatively standard

Hollywood production is surprising. I read his armchair review, which occurs in Some of the Dharma (page

124), three years ago and was impressed by his very negative reaction. Here is what he wrote:

WITH 'THE EGYPTIAN' Darryl Zanuck has purveyed a teaching of

viciousness and cruelty. They present him with a gold cup at banquets for this. The

author, Mika Waltari, is also guilty of the same teaching of viciousness and

cruelty. You see a scene of a man choking a woman under water. Both these men

are rich as a consequence of the world's infatuation with the forbidden murder,

— its daydreams of maniacal revenge by means of killing and Lust. Men kill

and women lust for men. Men die and women lust for men. Men, think in solitude;

learn how to live off your sowings of seed in the ground. Or work 2 weeks a

year and live in the hermitage the rest of the year, procuring your basic foods

at markets, and as your your garden grows work less, till you've learned to live

off your garden alone.

QUIETNESS AND REST THE ONLY ESCAPE.

The secret is in the desert.

Now, Ain't that Peculiar! The Egyptian tells the story of a man

disillusioned by romantic love — in the first half he loses his whole

self, his deepest self, to the wily and nefarious siren of Babylon.

The Egyptian envisions his then turning aside from the world, and

becoming a kind of medical “gentleman of the road”, a Sal Paradise of

the ancient Mediterranean. With Kerouacian pessimism, Sinuhe observes

the fruitlessness of human endeavor, and does so over and over again.

Finally, back home in Thebes — I love writing those words — he

becomes enlightened by Akhenaten, the Sun (One) worshiper, who reveals

to him that God is the whole of Reality, and that Forgiveness, of all

things, is at the core of that Reality. There is something like

pantheism here, together with absolving Christianity, and the the name

“Jesus Christ” is invoked on the end-title. How could Kerouac not have

responded positively to this, given his Christo-Buddhism, or

Buddhist-Christianity, or however you want to call his personal

synthesis?

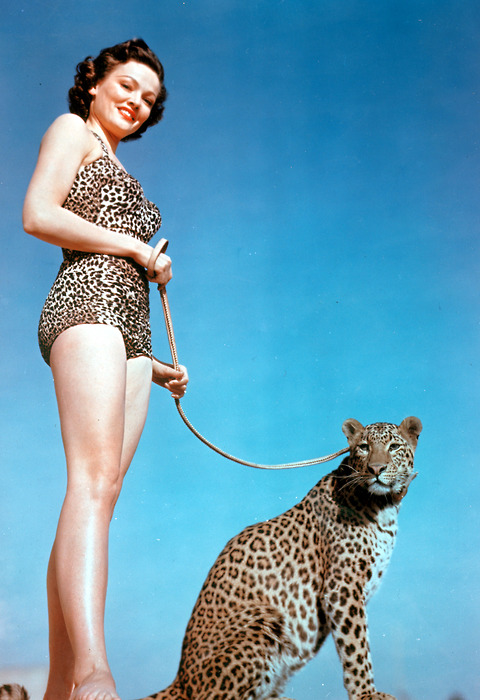

But he didn't like the film. He focused completely on the Woman of

Babylon sequence, with its subtle, slightly-off-frame drowning of the

Siren — she survives — and the “lust of the eye” and lust of the body

which drives the story at that point. Biographers of Jack Kerouac

would probably observe in these comments his suspicion of entrapping

women and entrapped men, his frequent equation of greed and lust, and

his persistent failed efforts to choose celibacy on Buddhist grounds

— “Men . . . learn how to live off your sowings of seed in the ground [my emphasis].”

I want to guess that Kerouac got stuck on the performance by Bella

Darvi as Nefer, the Woman of Babylon, and did not consider the enduring

Treue of Jean Simmons' character, nor the emphatic world-renunciation

by Sinuhe, which begins and ends The Egyptian.

What his impassioned observations do tell us, and they read as sober

and non-Benzedrined, is that Kerouac was touchy about violence. This

is the man who would brawl in bars, mad-drunk, and then write

remorseful exhortations to the whole world to Be Kind. He was also a

man who loved women, but suspected them, and their “designs”, through

and through, with the exception of Gabrielle, his mother.

Take a look at The Egyptian. It's a good movie. Sure, it's too long.

And to be sure, there's not one word of humor. But the liturgical

scenes, with their ethereal religious chants praising “Beauty” (I

thought I could hear Lionel Ritchie's “You are so Beautiful”) — which

work! — and especially the obeisances, including Jean Simmons's, on the

steps of the temple of the One (Sun) God, are sincerely reverent, and

affecting.

You could compare the scene of Pharaoh's archers breaking into the

Temple of Aten with the Roman breach of the Temple in Nicholas Ray's

The King of Kings. The latter is bloody and sensationalistic (like the “Civil War” cards little boys loved in the '60s, by the same people who

did the “Mars Attacks” cards) — the former, sympathetic and pitiful.

My irony for today is this:

Jack Kerouac should have liked The Egyptian. The title character, take

away the toga, is the man himself.

Maybe he walked out before the end. The editor of this blog taught me never to

do that.