Bob Dylan’s vocal instrument is not what it used to be but it’s still an expressive tool of great subtlety and power — still capable of the raspy lyricism of a Louis Armstrong or the growling fierceness of a Charley Patton. Armstrong and Patton were of course two of the greatest singers of all time, even though you wouldn’t describe either of their voices as dulcet. Dylan in his later years has taken his place in their company and his new album Shadows In the Night proves that.

Dylan is no longer capable of the effortless crooning he could pull off when he wanted to in his youth, so there’s something conceptually exciting about his decision to make an album of songs suited to a crooner — songs from The Great American Songbook associated with Frank Sinatra.

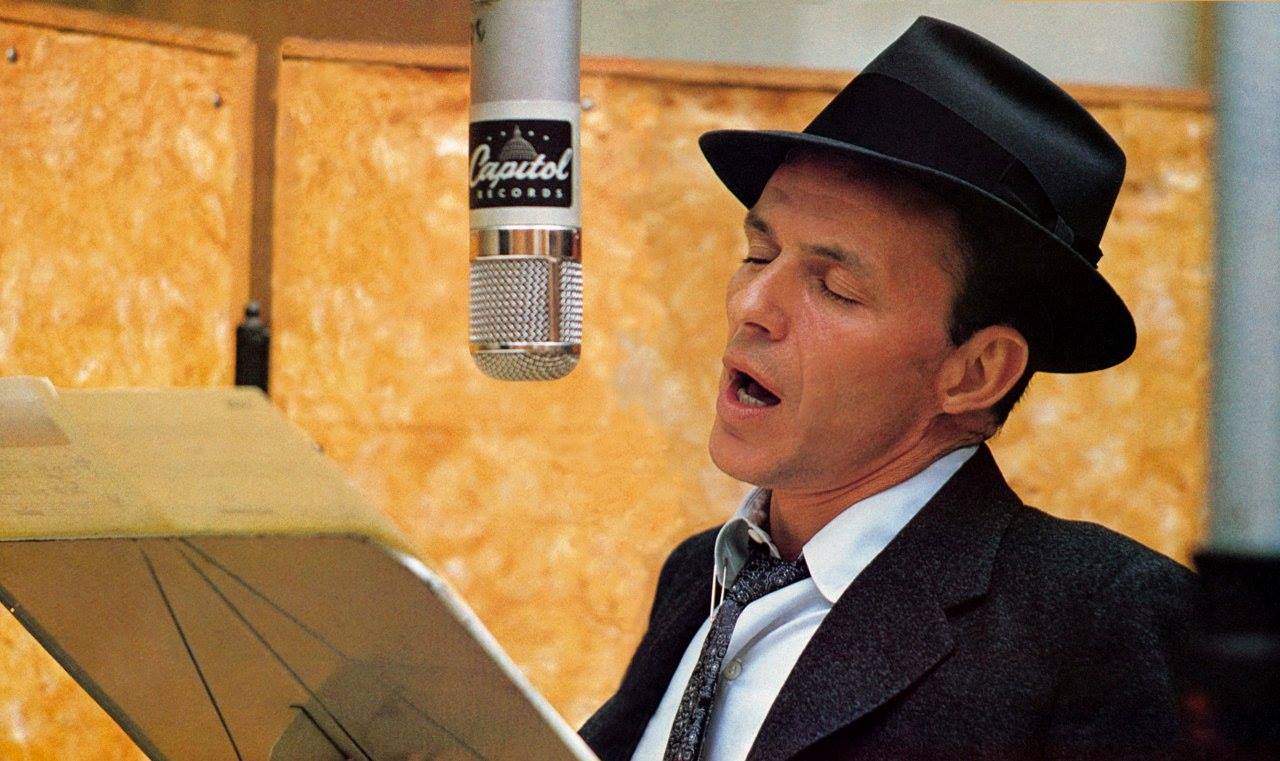

In the 50s Sinatra himself moved from sweet-toned crooning to a more conversational and dramatic approach to songs, but his pipes had never been better. Dylan shows what you can do with a Sinatra song without the pipes — with timing, inflection, breath, total emotional commitment.

Total emotional commitment is the key factor — the sort of embrace of a song’s dramatic meaning that puts the singer in its service without reservations of any kind. Dylan once said that Sinatra was one of the only singers who sang without a mask — meaning, I think, without the stylistic flourishes that distance a singer from the purely expressive task at hand. (This wasn’t always true of Sinatra, but it was almost invariably true of the albums he recorded for Capitol in the 50s.)

Dylan sings without a mask on Shadows In the Night. To call the results astonishing is to put it mildly. Part of what’s so moving about the album is that Bob Dylan, an iconic rebel, a great though eccentric songwriter in his own right, surrenders utterly to the lyrics and the melodies of songs written for mainstream audiences. It’s his way of honoring the greatness of these songs, honoring them in the highest way possible by giving them everything he’s got as an artist.

The songs Dylan chose for the album are mostly slow and melancholy numbers — songs of longing and loss. When Sinatra recorded his best versions of these songs he was a man in the prime of life, which gave his expressions of longing and loss a particular kind of poignancy. Dylan sings them here as an old man, which gives them another kind of poignancy, the poignancy of longings for things that may never be possessed, losses that may never be recovered.

Dylan has said that he knew he could never measure up to Sinatra’s performance of these songs, but he knew he had something of his own to bring to them — something Sinatra didn’t always bring to them when he grew old, when his instrument began to fail. In his later years Sinatra got saucy and flip with standards at times — he put on a stylistic mask in that sense. (Listen to Sinatra’s last recording of “Some Enchanted Evening” done for his own label Reprise, a song Dylan sings so sublimely here — Sinatra’s last version is an upbeat, jazzy rendition that completely eviscerates the emotional burden of the song.)

Dylan, standing shockingly exposed, cuts deep on every track of Shadows In the Night — cuts to the bone, carves these old songs into the fleshy tablets of the heart. They have an unsettling intimacy — as though Dylan has decided to sit you down in person in the booth of a deserted saloon and tell you how things really are, how they’re going to be.